As we move into the new year we take time to look back over 2023 and reflect on the work of Archives and Special Collections in the last twelve months.

Wellington 40

2023 was a significant year for the Archives as it marked the fortieth anniversary of the arrival of the papers of the first Duke of Wellington at Southampton after they were allocated to the University under national heritage legislation. The collection arrived on 17 March 1983, bringing to Southampton the University’s first major manuscript collection, leading to the creation of an Archives Department and the development of a major strand of activity within the University Library.

To celebrate this momentous occasion we hosted a number of events and activities throughout the year. It started with a Wellington 40 Twitter campaign, where both staff and researchers who had worked on the archive shared their favourite Wellington document. In March (the month when the collection arrived) we ran a series of blogs looking at forty years of work on the collection; conservation; events and the Wellington Pamphlets collection. This was followed by a series of Wellington themed blogs using the letters of the Duke’s name – starting, appropriately enough, with W for Waterloo.

On 7 July we hosted an in-person event, providing attendees with the opportunity to see behind the scenes, meet the curators and learn more about the work of the Archives and Special Collections, including conservation. As well as a selection of archival material on view, there was also an exhibition in the Level 4 Gallery reflecting on forty years of curation of the collection. And the visit was rounded off with tea and a talk by Dr Zack White about his research on the Wellington Archive.

In October, the Special Collections Gallery opened again for the first time since 2020 with an exhibition The Duke presents his compliments. Taking the Wellington Archive as a starting point, the exhibition looks at the development of the archive collections since 1983. It continues to run weekdays (1000-1600) from 8 January to 16 February, so there is still time to come and have a look.

Events

As well as the event hosted by Archives and Special Collections as part of the Wellington 40 celebrations in July, we hosted visits for the Jewish Historical Society of England on 9 October and for the Come and Psing Psalmody event at the Turner Sims concert hall on 22 October. This latter event showcased some of the West Gallery music material collected by Rollo Woods, who was an expert in this field as well as a former Deputy Librarian at the University.

In November we ran an activity for the Hands-on Humanities day at the Avenue Campus. For the activity intrepid travellers were asked to take their archives passport and embark on a journey learning more about the collections. Feedback from those attending was very positive, with participants finding it a fun way to find out about the collections and the university. Highlights noted were “learning about history”, “discovering unexpected items” and, of course, “using the quill”.

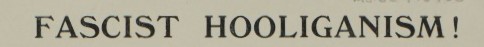

The Archives and Special Collections has continued to support teaching and research throughout the year, hosting sessions introducing students to archives for a range of undergraduate and master courses. Karen Robson and Jenny Ruthven have been involved in leading sessions on the curation of specialist libraries and on archives for the new MA in Holocaust Studies that runs for the first time in 2023/4. Karen will be leading further practical sessions on this course in the second semester in 2024. We also led two group projects as part of the second-year history undergraduate course in early 2023. This course asks the students to focus on archive sources for their project and for this year we offered a project about nineteenth-century press and politicians, utilising material from the archive of third Viscount Palmerston, and a project based on the papers of the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry.

Collections and projects

Although the collection arrived and was reported in the review for last year, the Ben Abeles archive was officially launched in an event hosted by the Parkes Institute in June 2023. Karen Robson formed part of the panel for this hybrid event which attracted an international audience. Details of the Abeles collection is accessible in the Archive Catalogue.

Amongst the new Jewish archival and interfaith collections for 2023 were the papers of Professor Alice Eckardt, a leading scholar and activist in the field of Christian-Jewish relations, relating to her connection with a leading British figure in the same field – Revd Dr James Parkes. We have, throughout the year, acquired additional papers for existing collections, such as for Eugene Heimler and the Jewish Youth Fund. We also acquired more material documenting student life in previous decades with papers for the Med Soc reviews in the 1980s.

We have continued to develop our maritime archaeology archival holdings and the most sizeable acquisition of material this year has been the working papers of Peter Marsden relating to shipwrecks.

Part way through the year, Archives and Special Collections was the recipient of a grant from the Honor Frost Foundation for a project supporting work to make over 5000 digital images created from slides in the Honor Frost Archive, together with catalogue descriptions for each of the images, available online. The project is due to be completed by 31 January 2024.

Archives searchroom services

2023 saw the expansion of the Archives and Special Collections Virtual Reading Room service offering remote access to collections through digital appointments. This is a growing element to the archive reading room service and usage has grown by 28% in the last year. For information on how to book a digital appointment look at the Special Collections website access page.

This usage has been paralleled by a growing quantity of enquiries being handled within Archives – rising by 11% in the last year.

Looking ahead

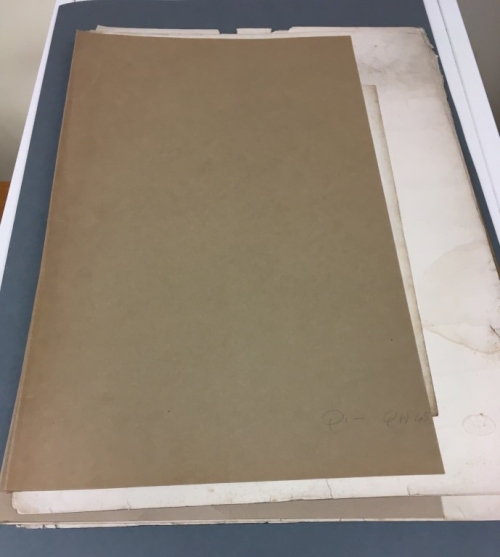

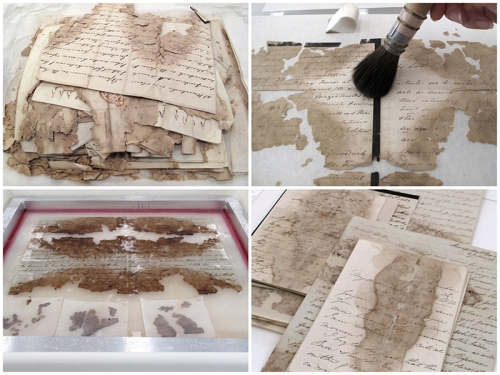

In 2024 we are looking ahead to marking the 240th anniversary of the birth of third Viscount Palmerston with events, including social media programmes and an exhibition relating to the Palmerston family and Broadlands. We have a number of projects ongoing and new for 2024, including working with the Parkes Institute to create a series of films promoting the collections and a three-year conservation project on the Schonfeld archive. Do look out for news on our social media channels.

![Michael Sherborne [MS434 A4249 7/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms-434_a4249_7_2-portrait-photo-of-michael-sherbourne.jpg?w=189)

![Young Michael Sherbourne, 1939 [MS434 A4249 7/3]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_7_3-young-michael-sherbourne.jpg)

![Michael Sherbourne and his wife Muriel in USA, 1989 [MS434 A4249 7/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_7_2-michael-sherbourne-and-his-wife-muriel.jpg)

![Michael Sherbourne on the telephone with his recording equipment, c.1980s-1990s [MS434 A4249 7/4]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms-434_a4249_7_4-michael-sherbourne-on-telephone.jpg)

![Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry calendar, 1989 [MS 434 A4249 5/6]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms-434_a4249_5_6-womens-campaign-for-soviet-jewry-calendar-1989.jpg)

![Poster for talk given by Michael Sherbourne on ‘Russian Jewry Past, Present, and Future’, 2004 [MS 434 A 4249 1/3 Folder 8]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_1_3-folder-8-michael-sherbourne-talk-poster.jpg)

![Front cover of We are from Russia by Paulina Kleiner translated from Russian by Michael Sherbourne , MS434 A 4249 2/1/1 Folder 1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_2_1_1_folder1-we-are-from-russia-front-cover.jpg)

![Michael Sherbourne on protest march in San Francisco near the Soviet Consulate, [MS434 A4249 7/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_7_2-michael-sherbourne-marching-in-protest.jpg)

![Tears, dirt and discolouration to an interpretation of Passio Domini Nostri Jesu, engraved by K. Oertel [cq N 8026, print no. 440].](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/04-illustration-1.jpg)

![Stains and discolouration to a lithograph of Miss Fanny Kemble, drawn on stone by R. J. Lane [cq PN 2598.K28, print no. 525]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/07/05-illustration-2.jpg?w=500)

![Letter from William Temple, Munich, to his mother Mary (Mee), Viscountess Palmerston, 11 July [1794]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/ms62_br32_1_1.jpg?w=300)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)