The Wellington Papers came to Southampton with a major challenge of conservation: some ten percent of the collection was so badly damaged it was unfit to handle and 10,000 documents were in a parlous condition. The University has made good progress: more than seventy percent has been conserved and is now available for research, including papers for 1822 (for the Congress of Verona), for Wellington as Prime Minister in 1829 (the year of Catholic emancipation), and for all of the Peninsular War.

Fundraising

A campaign to raise funds for the conservation of the Wellington Papers was launched in October 2010. Grants from the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust, the J.Paul Getty Jr Charitable Trust and the Rothschild Foundation as well as modest funding from alumni have supported the conservation of the badly degraded and mould-damaged papers from 1832.

Paper is susceptible to many hazards — water, mould, vermin, all have made an impact on the collection. As early as 1815, part of the archive was damaged in a shipwreck in the Tagus, when the vessel bringing back Wellington’s papers sank as it crossed the bar leaving Lisbon. Many parcels of letters were delivered to George Canning, the British ambassador in Portugal, and other British officials, and Canning ‘endeavoured to quicken the zeal of finders by promises of reward’. One package had passed through the hands of the Portuguese government, although the ambassador was unclear whether it had contained anything to gratify their curiosity. Seawater is not the best preservative of paper: many items were either completely lost at that stage or have become more susceptible to deterioration because of the damage they sustained in 1815.

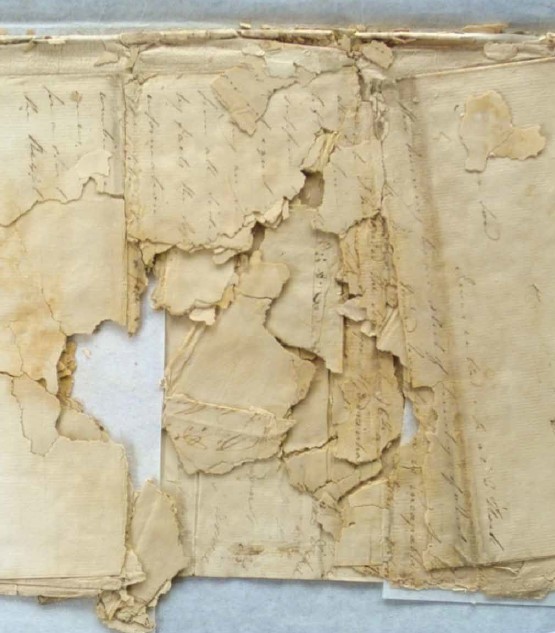

Fragmented bundles

By the late nineteenth century, much of the correspondence was arranged in tightly-folded bundles in chronological order, month by month. Some of these bundles are now badly damaged and very fragile. Most of this damage is the result of storage in a damp environment during World War II. Mould growth has severely weakened and stained the paper, leaving some letters in a fragmentary state. The pattern of damage through the bundles is the consequence of the way in which they were stored, with mould typically occurring along the side or fold of the paper on which the bundle was resting. Certain years have been damaged — 1822, 1829 and 1832 — and within 1822, only bundles of letters to the Duke, and not those from him, have been affected.

The conservation project has focused on the treatment of the mould-damaged bundles from 1832. The conservators began by working with the less severely damaged materials so that they were able to build up expertise in conserving this type of exceedingly fragile material before tackling the most fragmentary bundles.

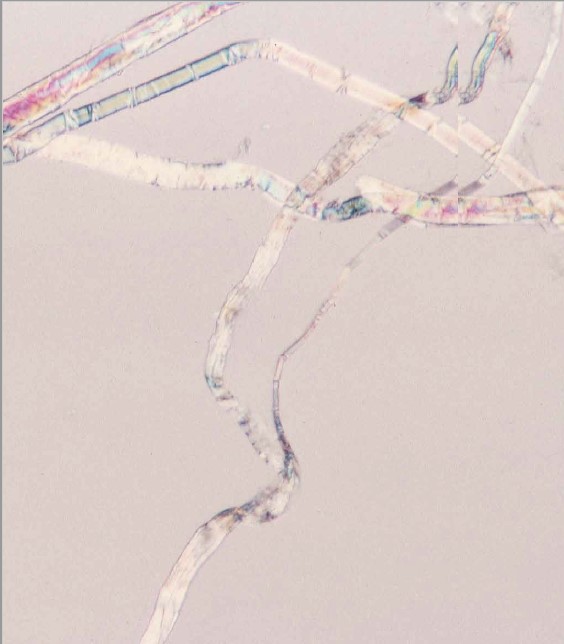

Fused paper

A number of bundles from 1809 and 1811, the period of the Peninsular War, had been unfolded and interleaved with twentieth-century lined paper. Original papers and interleaving sheets are now both severely weakened due to fungal growth. This has penetrated through the layers of paper, causing areas to fuse together. Microscopic examination shows the long thin filaments of the fungal structure intertwined with the paper fibres. Documents were separated manually and collated. Separation, particularly of the most severely damaged bundles, is a painstaking and time-consuming task. In some instance papers have fused together due to compression whilst damp and great care is necessary to prevent disintegration of the paper.

Fibre analysis

Each bundle was documented before and during conservation treatment, noting paper characteristics, such as watermarks. Microscopic examination was used for fibre analysis and to determine the extent of mould damage. Most of the paper is European, but there are also oriental papers and very thin Western paper, used for making copies. Fibre analysis indicated that the majority of the British papers contained hemp and linen fibres with a small number of cotton fibres seen in some of the later papers. These would have been made from linen and cotton rags as well as possibly old rope, canvas and sails. A high proportion was made by the firms J. Whatman, S. Pike and J. Larking. These papers are generally quite thick, with dense and closely packed fibres and have a thick application of size, a gelatine, like glue, that strengthens the paper. They are usually off-white in colour, though there are a number of blue/grey papers. The smaller percentage of European, mainly Spanish and Portuguese papers, are of a similar composition, though some contained other plant fibres. The paper is usually quite thin and is either lightly sized or unsized. They are generally off-white to beige in colour.

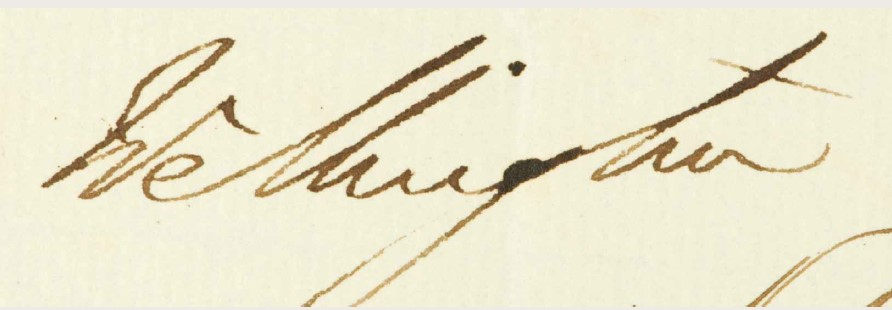

Inks

The majority of the writing is in iron-gall ink, which varies in colour according to the ink recipe used, from light brown to nearly black. In some instances it has faded or is obscured by staining, and in others it has corroded. Although iron-gall ink is stable in water, corrosion is accelerated by moisture causing the ink to ‘burn through’ the paper. Before undergoing water-based conservation treatments, the documents were treated with calcium phytate to inactivate any soluble iron (II) and iron (III) ions.

Steps in conservation

Surface cleaning: Letters were cleaned where possible using soft, goat or sheep’s hair, Chinese brushes. Chemical sponges were used to remove dried, powdery mould residue.

Aqueous treatments: pH tests showed that most documents were fairly acidic. They were washed in cold and warm water to remove discolouration and soluble degradation products. The papers were then deacidified using calcium hydrogen carbonate.

Repair: Documents were humidified and loose fragments realigned where possible. The paper was then lined with Japanese tissue, adhered with Shofu, a Japanese wheat starch paste. The lining acted as a support to both hold fragments in position during the repair process and also to prevent tearing of the original at the weakened, mould-damaged edges. This can occur as the result of tensions between new and old papers as they dry at different rates.

Missing areas were infilled using a technique known as leaf-casting. This creates new paper made from pulp similar in nature to the original paper. The result is a sympathetic repair, which strengthens the weakened area, without putting undue stress at the repair edge.

Repairs were trimmed to the document which is then strengthened by an application of size, either gelatine or methyl cellulose.

Storage: Documents were stored in 100% cotton, acid-free folders and boxes.

The expertise gained by the conservators in leaf casting has enabled them to concentrate on the most fragile items with work underway on the separation and stabilisation of more than 10 bundles of 407 documents. These present some of the most severe conservation challenges as the separation of fragmented material can take several months to complete before any treatment is possible.

Public access

Many of the fragmented bundles for 1832 are now accessible for the first time since the 1940s. This is historically very significant material as it includes the first Duke of Wellington’s papers relating to the first Reform Act. As Wellington was the leader of the Tories in the House of Lords during the progress of the Act, by enabling archivists to access and catalogue the material, the whole picture of the debate is now available. The catalogue descriptions produced, which include detailed item level descriptions of each paper, are currently being added to our online catalogue.

The papers themselves will be made available to researchers in a number of different ways. The original material can be consulted in the Archives and Rare Books Reading room or via our digital appointment system. Digital copies also are used as part of the Special Collections online exhibitions and as part of teaching resources for student sessions.

Substantial progress has been made with this project, the largest conservation task the Special Collections Division has undertaken.

Please look out for our next blog post marking 40 years of us holding the Wellington Papers, which will focus on events.

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)

Pingback: 2023 – a year in review | University of Southampton Special Collections