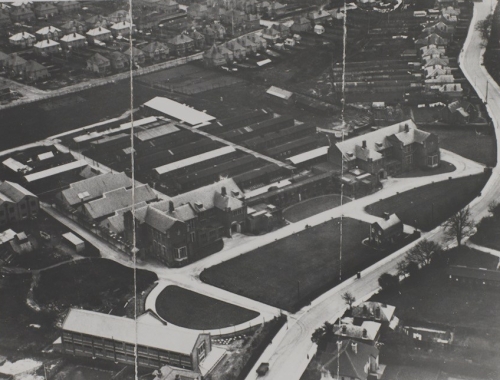

As we move into the 1920s, we find the University College settling into its new Highfield site. By 1922, we were home to a grand total of 350 students! In 1925, 32 of these students secured honours degrees, with 9 placed in the first class. While there were 14 departments in total, the bulk of the student body was made up of trainee teachers, engineers and a large contingent of ex-service men financed by Ministry of Labour; those reading for a degree were in a small minority. In terms of staff, the University College had 10 professors, 4 readers, 20 lecturers and 4 demonstrators. The administrative staff consisted of the Registrar, David Kiddle, plus two male clerks. Principal Vickers recounted “what they lacked in numbers […] they made up for by devotion to the interests of their students and their loyalty to the college.”

Exterior view of the University College, south wing, with staff and students, c. 1920-5 [MS1/Phot/39 ph3112]

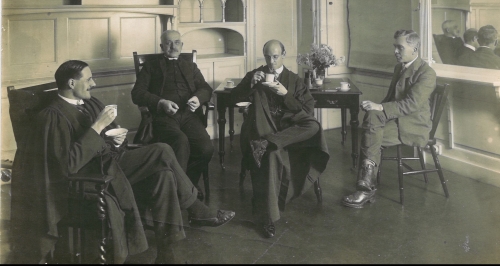

Staff common room at South Stoneham House [MS1/2/5/17/246]

Betty Wicks and other residents pictured outside South Hill Hall of Residence, c. 1928-9 [MS224/12 A919]

Group photograph outside the winter garden of Highfield Hall, c. 1928, with some of the women in fancy dress. [MS1/Phot/39 ph3133]

Kenneth Hotham Vickers, Principal of the University College 1922-46, seated at his writing table [MS1/Phot/39 ph3415]

The best and most fruitful stage of my education began when I took up residence in Southampton in September 1922 with very little conception of what lay before me […] On my first day in College I was waylaid by the Professor of Physics who was alarmed at the dangerous condition of his first floor lecture room, which was showing signs of subsiding […] On the whole, the accommodation was sufficient for the work then being done, but the huts were an eyesore, and their upkeep and heating a constant worry. [MS113 LF780UNI 2/7/85/101]

Professor John Eustice was Vice Principal throughout the decade.

At the start of the decade, Albert Cock was appointed as Professor of Education and Philosophy. That same year, the University gained a Chair of Modern Languages with the promotion of Patchett from German lecturer and H.M. Margoliouth as Professor of English Language and Literature.

English graduates including Professor Margoliouth [MS1 A4108/3]

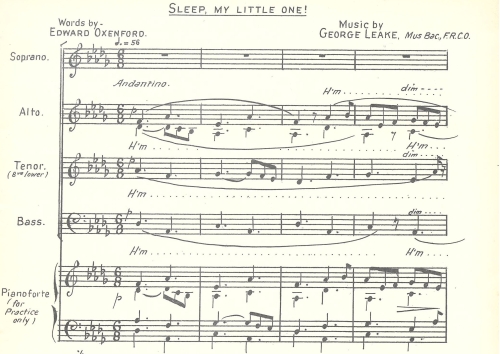

Sheet music for Sleep my little one, set to music by George Leake

The Department of Law was created in 1923. In 1926, Dr W.Rae Sherriffs was appointed first chair of Zoology. That same year, the University College was joined by Percy Ford who worked towards building a faculty not just of economics but social sciences.

The Engineering Faculty also saw great expansion with a scheme of part time and day and evening training for apprentices of local engineering and shipbuilding firms. The project was supported by Messrs. Thornycrofts and Co. of the Supermarine Aviation Works at Woolston and of the Avro Works at Hamble.

Principal Vickers gives an honest account of the physical condition of the Highfield campus:

Standing in acres of ground lying either side of a public road, it consisted of two wings of the original design joined together by a covered way. As an after thought, three small laboratories and a building for the Engineering Department, all “semi-permanent” structures, had been erected behind these two wings. The Hospital authorities had added a large number of wooden huts of “temporary structure”, which were sold to the College.

Aerial view of the University College looking east, showing part of University Road and Hartley Avenue, c. 1928-9 [MS1/Phot 39 ph3211]

The main structure was not very prepossessing and suffered from the addition of certain stone adornments; it was built of unattractive brick. Already it was showing signs of unsteadiness. In front of the College there was an unmown hay field, at the back all the unoccupied space was a wilderness. Across the road, in front of the College were more huts.

Exterior view of the University College, north wing, c. 1925 [MS1/Phot/39 ph3099b]

Department of Botany: the main laboratory showing Professor Mangham with students [MS1/2/5/17]

A good social life was as important for students then as it is now. This dance card from 1921 shows that nights out were somewhat more formal 100 years ago.

Dance card for a soiree at the Royal Pier Pavilion, 24 February 1921 [MS224 A908/1/3]

Tennis team, 1921 [MS1/Phot/39 ph3164]

Photo the RAG concert, 1928-9 session, taken from the papers of Betty Wicks [MS224/12 A919/5/2]

By the end of the decade the University College had faced its fair share of challenges, many financial, but was well established at its Highfield home. We will close with Principal Vickers reflections on the University College, Southampton spirit:

Not many days had gone by before I realized that there was that corporate spirit and devotion to all that the College stood for, which can only be learnt fully by those who have together passed through days of danger and tribulation […] There was in the College something which was intangible, but very real, compounded of a belief in University education, a devotion to the place and their job and their readiness to give the raw young Principal all the backing that he needed. [MS 113 LF 780 UNI 2/7/85/101]

![Cover of Cleyn album [MS292]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms292_a1013_frontcovercrop.jpg?w=383&h=510)

![Drapery studies by Cleyn, including kilt of Roman soldier [MS292 f.18r]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms292_a1013_p18r_detaildraperies.jpg?w=500&h=364)

![Sketch by Cleyn of winged putti [MS292 f.5r]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms292_a1013_p5r_detailputti1.jpg?w=255&h=310)

![Preparatory sketch by Cleyn for a tapestry ‘Perseus and Andromeda’ [MS292 f.34r]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms292_a1013_p34r_perseus.jpg?w=500&h=415)

![Drawing of two chain bridges by Marc Brunel [MS 61 WP1/679/8]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/brunelbridge.jpg?w=500&h=287)

![Tunnelling shield: drawing by Marc Brunel, 1838 [MS 61 WP/2/49/34]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/brunelshieldwp2_49_34_crop.jpg?w=500&h=232)

![Letter from Brunel relating to tunnelling shield, 1838 [MS61 WP2/49/33]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/brunelshieldletter_crop.jpg?w=427&h=372)

![Plan of the Wapping shaft: drawn by Brunel, 1842 [MS61 WP2/83/12]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/brunel_ms61_wp2_83_12.jpg?w=500)

![Reply from Wellington to Brunel, 29 March 1844 [MS61 WP2/118/15]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/brunelreply.jpg?w=450&h=404)

![Michael Sherborne [MS434 A4249 7/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms-434_a4249_7_2-portrait-photo-of-michael-sherbourne.jpg?w=189&h=300)

![Young Michael Sherbourne, 1939 [MS434 A4249 7/3]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_7_3-young-michael-sherbourne.jpg?w=500)

![Michael Sherbourne and his wife Muriel in USA, 1989 [MS434 A4249 7/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_7_2-michael-sherbourne-and-his-wife-muriel.jpg?w=500)

![Michael Sherbourne on the telephone with his recording equipment, c.1980s-1990s [MS434 A4249 7/4]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms-434_a4249_7_4-michael-sherbourne-on-telephone.jpg?w=500)

![Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry calendar, 1989 [MS 434 A4249 5/6]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms-434_a4249_5_6-womens-campaign-for-soviet-jewry-calendar-1989.jpg?w=500)

![Poster for talk given by Michael Sherbourne on ‘Russian Jewry Past, Present, and Future’, 2004 [MS 434 A 4249 1/3 Folder 8]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_1_3-folder-8-michael-sherbourne-talk-poster.jpg?w=500)

![Front cover of We are from Russia by Paulina Kleiner translated from Russian by Michael Sherbourne , MS434 A 4249 2/1/1 Folder 1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_2_1_1_folder1-we-are-from-russia-front-cover.jpg?w=500)

![Michael Sherbourne on protest march in San Francisco near the Soviet Consulate, [MS434 A4249 7/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_7_2-michael-sherbourne-marching-in-protest.jpg?w=500)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)