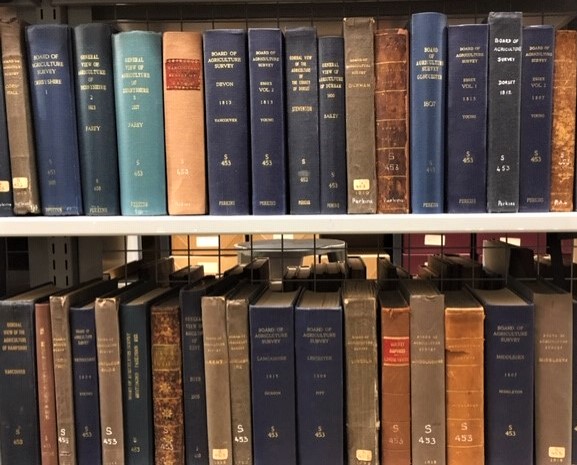

As winter approaches, keen cooks will no doubt be getting out their recipes for nourishing soups and stews and hoping, supply chains permitting, to obtain all the ingredients they need. That this was not possible for much of the past is made clear in the Perkins Agricultural Library books which testify to the amount of planning and work involved in preserving or storing food for winter, or even for short periods of time throughout the year.

Whilst most of the books in the collection are concerned with farming practice, some are essentially manuals of country living, advising their readers on how to be as self-sufficient as possible. The Complete Family-Piece and Country Gentleman and Farmer’s Guide (1739) is one such book. Consisting of three parts, it claims to contain over a thousand “receipts” for both food and medicines – Leprosy treatment follows Lent potato pie in the index. A comprehensive guide, it also advises on hunting, shooting and fishing, cultivating fruit, flower and kitchen gardens, improving the land and managing a farm.

Although autumn was a peak time for preserving foods of all kinds, with livestock which could not be fed over winter often being killed around All-Hallows Day, (1 November), the summer months were no less busy, with recipes for preserves calling for fruit, such as strawberries and currants to be not “full ripe” to ensure the best results.

Traditionally, foods were preserved through curing, pickling and sugaring. Curing was used mainly for meat, with salt or brine removing moisture to prevent microbial growth, a process which might be followed by smoking. Pickling required the food to be immersed in an acidic solution such as vinegar to kill bacteria, with herbs and spices being added for flavour, whilst in sugaring the food was dried and packed in sugar or in liquids such as honey or sugar syrup. A riskier method and potential cause of botulism, was potting, in which cooked foods, usually meat, were sealed in solidified fat within earthenware containers.

Published “Purely for the Good of private Families”, the Complete Family Piece contains a chapter of “many excellent Receipts for Picking and Preserving of all Sorts of Fruits, Tongues, Hams &c which will, no doubt, be found very beneficial to all private Families, in as much as by the Help of this Chapter, they may have all those Things in good Order throughout the year.”

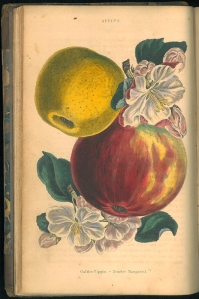

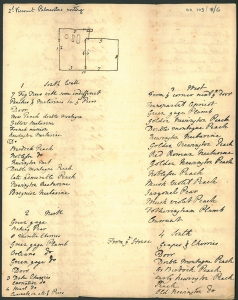

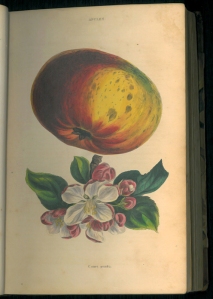

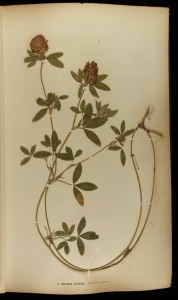

Amongst the pickling recipes are those for meat, fish, nuts and vegetables, including mushrooms, French beans, artichokes, walnuts, oysters, herrings, pork and salmon, whilst the recipes for preserving include green fruits, apricots, gooseberries, apples, raspberries, cherries, currants and dried fruit.

Some of the foods and processes – salting bacon and ham would be familiar today, others, pickling sparrows or potting curlews, less so. Potted goose and turkey (a similar idea to a two bird roast) with an instruction to “Keep it for Use, and slice it out thin” may not be an option this year, but there is a recipe for keeping peas till Christmas – by cooking them and bottling them in mutton fat.

Another manual for country living The Country Housewife’s Companion by William Ellis (1750) is rather more forthright in the advice offered to the wives of country gentlemen, yeomen and farmers. Ellis pronounces, for example, that “it is Very ill Housewifery to buy Bacon or pickled Pork at Shops” (as is done by thousands) when there is Conveniency to prevent it, by feeding Swine at home.” Other more general advice was that a wife should keep “a Pair of Scales by her, in readiness to weigh the Goods she buys” and make sure that servants did not lie too long in bed – “to rise at Five is the Way to thrive.”

Given Ellis’s views on pickled pork, it is no surprise that he includes ten pages on it amongst the many recipes for preserving food. It is a meat praised as being “the cheapest Sort, but is ready at a minute’s wanting it, to become pleasant, wholesome, hearty Meal; either eaten cold or fry’d … most of the good housewives of Farmers … commonly prepare and keep souced Pork by them (at times) from about Michaelmas ‘till Lady-Day”.

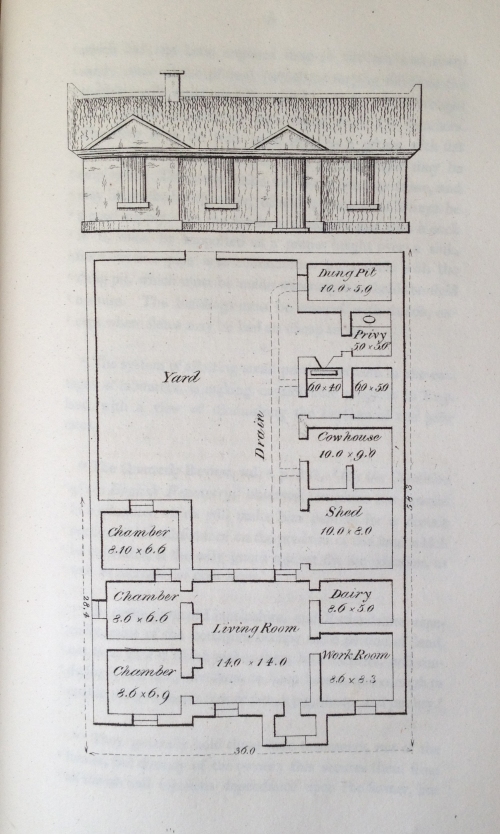

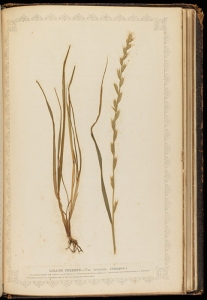

There is also advice on storing fruit and vegetables, with variations supplied by a “Lord’s Gardener” and “Hertfordshire women” amongst others. Apples could be stored in layers of straw on a chamber floor or by layering them in straw within a cask which was then buried. Peaches, nectarines and apricots were layered in wood ash or sand in a box. Methods of storage for vegetables included barrelling broad beans and peas in straw or chaff, and root vegetables such as carrots and potatoes were stored in straw lined pits, or as suggested by one Lord, brought into a ground room and stored in a thatched pile, which was then covered by gravel.

Guides of this kind were clearly aimed at households of a certain standing, the country wives having servants and directing operations, not necessarily undertaking them themselves. For farmers’ wives, ensuring that there was sufficient food for the fluctuating number of seasonal workers as well as for the household was a particular concern and whilst the advice given in the guides appears comprehensive, how useful it was is known only by the owners, such as Jane Dean, owner of the Library’s copy of The Country Housewife’s Companion.

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)