This summer will see further refurbishment taking place in the Hartley Library, the University’s main library and home to its Archives and Special Collections. Further information regarding its impact on the Special Collections Division can be found on our website.

While the University Library today has a presence on all seven campuses of the University, for this week’s blog post we will be taking a look back at the development of the University’s main Library on the Highfield Campus.

The “old Hartley” Library (1860s-1910s)

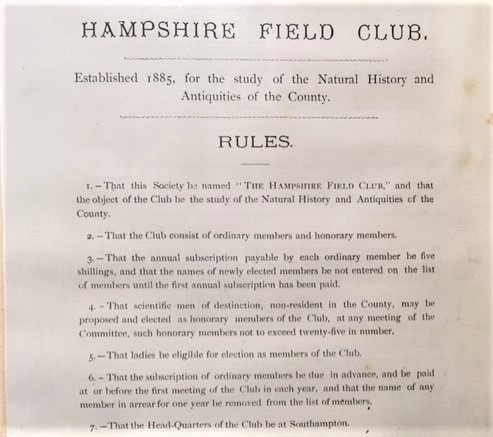

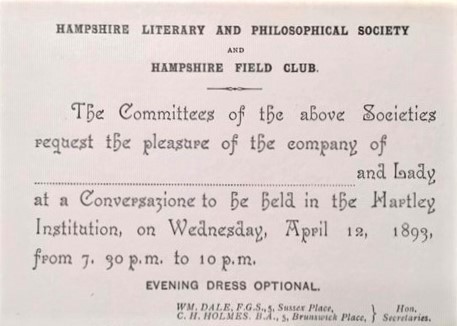

The University of Southampton has its genesis in a bequest left by Henry Robinson Hartley, a studious and reclusive character and heir to a family of Southampton wine merchants. In his will Hartley bequeathed a large proportion of his estate to the Corporation of Southampton and called for “a small building to be erected…to serve as a repository for my Household Furniture, Books, Manuscripts, and other moveables”. Out of this the Hartley Institution was formed.

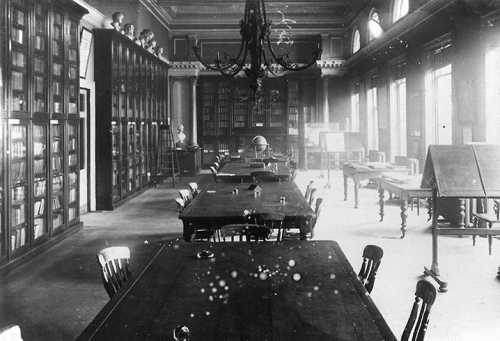

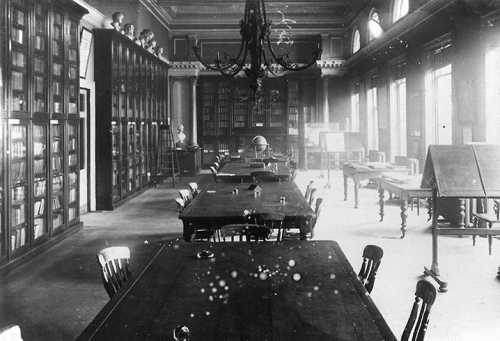

Hartley University College Library, c.1910

The original Hartley Institution building, located on the High Street, below the Bargate, was declared open by Lord Palmerston on 15 October 1862. It comprised of a library, museum, and reading room, together with a lecture hall and classrooms. While the Library was initially only accessible to members of the Institution, it was made freely open to the public in 1873. As a result, it acted as both the Institution’s academic library and the town’s public library.

Over the subsequent decades the institution increasingly focused on meeting the demands for popular and industrial education. This resulted in its transition to a university college in 1902, when it became Hartley University College. By 1910, further developments in this direction emphasised the need for premises more fitting to the institution’s ambitions. This prompted a move from the cramped accommodation on the High Street to the Highfield Court Estate on the outskirts of town. However, the move was not welcomed by everyone. Some of the townspeople resented the loss of the privilege of access to the Library, which “they had continued to value in spite of the existence of a free Borough Library since 1889.”

Moving to Highfield (1910s-20s)

The grand opening of the renamed University College of Southampton by Lord Haldane took place in June 1914. The new buildings at Highfield consisted of two separate wings housing an arts block and a range of single story laboratories for biology, chemistry, physics and engineering. However, a lack of funding meant that the construction of the administration and library building, which should have filled the gap between the two wings, was postponed.

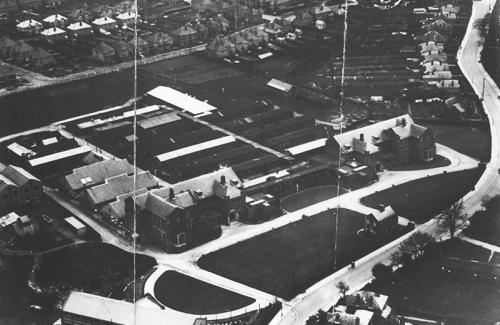

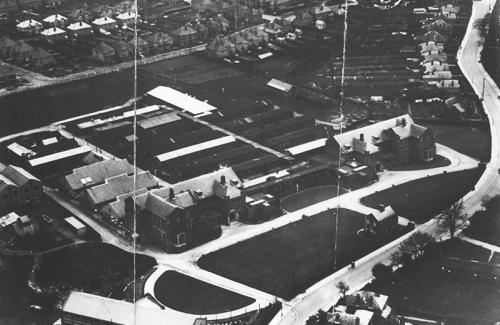

Early photograph of the University’s Highfield site. The building in the foreground is now the south wing of the Hartley Library.

Six weeks after the official opening the country declared war on Germany. As a result, the move to Highfield was indefinitely postponed with the College offering the buildings to the War Office for use as a hospital. As the war progressed, the main building proved too small to accommodate the increasing number of wounded soldiers and extra wards were constructed in temporary wooden huts to the rear.

Aerial photograph of the Highfield campus with the wooden huts at the rear of the main buildings, c.1932

The War Office eventually gave up the buildings in May 1919 and University College of Southampton began the session of 1919-1920 in its new home, continuing to make use of the wooden huts. Since it had originally been intended to form part of the central block between the two wings, none of the existing buildings had room specifically set aside for a library. A large room on the first floor in the northern wing of the main building served as a reading room and also housed a selection of the books most in use. However, these were only a fraction of the 35,000 volumes which the Library now possessed, with the majority of the books dispersed through the corridors and huts.

The Turner Sims Library and Gurney-Dixon Building (1930s-50s)

The completion of the central block had to wait until the 1930s when the construction of the Turner Sims Library was made possible by the donation of £24,250 by the daughters of Edward Turner Sims, a former member of Council. The Turner Sims Library, which now forms the front of the present Hartley Library, was opened by H.R.H. the Duke of York (later King George VI) in October 1935. The new building filled most of the gap between the two parts of the original building (which now make up the north and south wings of the Hartley Library).

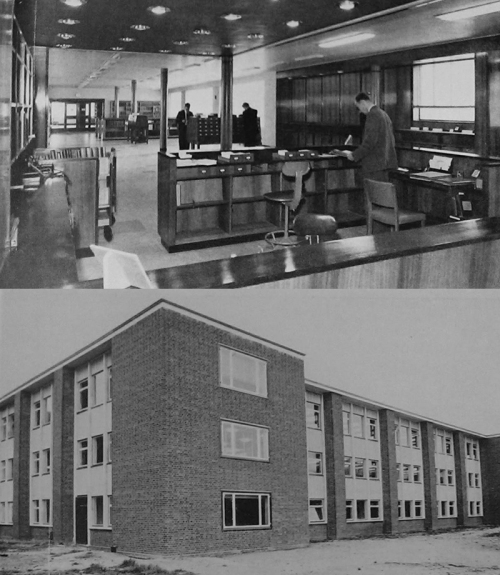

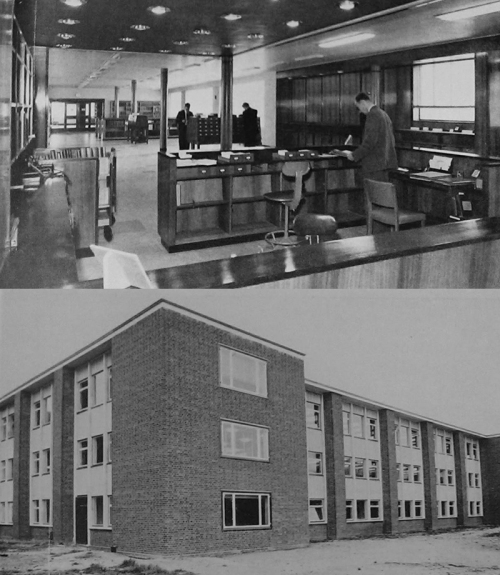

Photographs of the Turner Sims Library, opened in 1935

While this was welcomed as a long overdue improvement, space remained an issue. Planning began for a much larger extension in 1947 but it wasn’t until 1959 that the Gurney-Dixon Building at the rear of the Turner Sims Library was finally declared open. The extension was named after Sir Samuel Gurney-Dixon who was chair of Council for 21 years. To mark the occasion he presented to the Library six rare editions of Divina Commedia, including a copy of the Brescia edition of 1487.

Photographs of the interior and exterior of the Gurney-Dixon Building, 1959

Developments in collections and services (1960s-80s)

In addition to its main stock, the Library had by now acquired a number of valuable printed special collections. These included the agricultural library of W. Frank Perkins, acquired in 1945. This trend continued with the transfer of the private library of Reverend Dr James Parkes to the University in 1964. Focusing on Jewish/non-Jewish relations, the Parkes Library originally consisted of 4,500 books, 2,000 pamphlets and sets of periodicals. Since that time the collection has expanded significantly and has led to the development the University’s special interest in Anglo-Jewish archives.

Opening of the Parkes Library, 1964

By 1969 the Library already housed over a quarter of a million books leading to a critical space problem. An extension to the first floor, for the Special Collections, was completed the same year and was followed by an extension to the north wing and mezzanine in 1970, with an ‘attractive and welcoming entrance’ ready by the end of the session. However, the Library’s stock continued to grow. The decade saw the arrival of the Ford Collection of British Official Publications. Originally brought to the University by Professor Percy Ford and his wife Dr Grace Ford, the collection formed the basis of the Parliamentary Papers Library which opened in 1971. Further efforts were undertaken to alleviate space issues in 1978, including the addition of a mezzanine floor to the Turner Sims part of the Library, creating a new area of 500 square metres.

During the same period, the Library was modernising its services. Between 1966 and 1968 the Library was one of the first in the country to introduce a computer-based issue system, employing punched cards. A decade later, this was replaced by a Telepen-based circulation system in 1979-80, making possible a complete up-to-date loan file at all times. An online circulating system was introduced in 1984, eventually replacing the off-line system entirely.

Opening of the Wellington Suite, 1983

A new chapter in the development of the Library’s Special Collections commenced with the arrival of the Wellington Papers in 1983, when the papers of the first Duke of Wellington were allocated to the University under the national heritage legislation. This led to the conversion of a part of the Library to provide an archives reading room and storage area, with the Wellington Suite being officially opened on 14 May 1983. The arrival of the Wellington Papers was to stimulate the acquisition of further significant manuscript collections which continues to this day.

The creation of the Hartley Library (1980s-2000s)

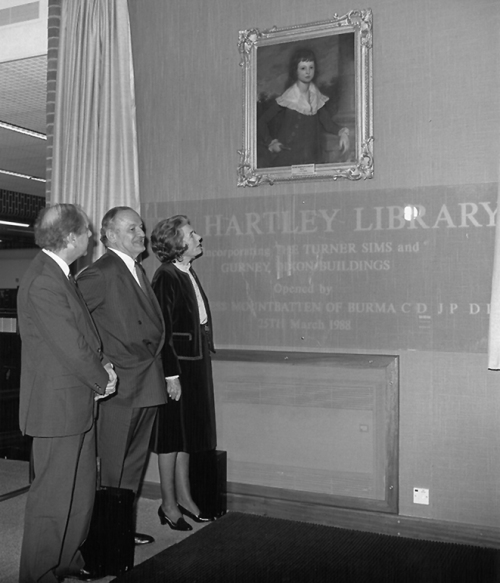

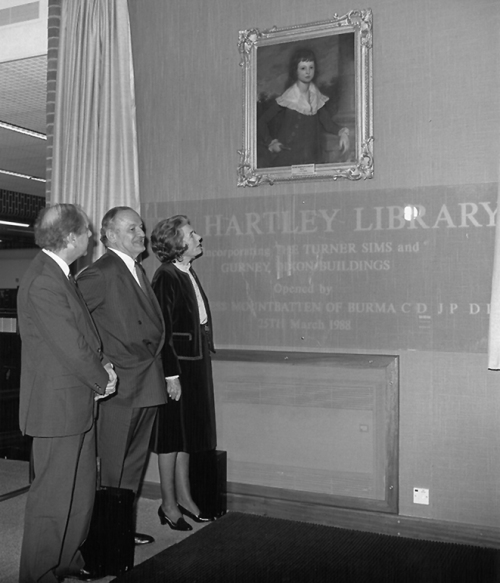

In the autumn of 1987 the University celebrate the 125th anniversary of the opening of the Hartley Institution. A special event of this jubilee was the opening of a remodelled Library, renamed the Hartley Library, by Countess Mountbatten of Burma.

Opening of the Hartley Library, 1987

The Hartley Library was in effect a new Library. It included new strongrooms and reading room for the Special Collections, which was now ready to accept the papers of Earl Mountbatten of Burman from the archives of the Broadlands estate in Romsey. As a result of such major acquisitions the Library developed an additional role, becoming an important centre for primary historical research. Further collections followed, including additional material from the Broadlands archives (notably the papers of third Viscount Palmerston) and the Anglo-Jewish Archives in 1990.

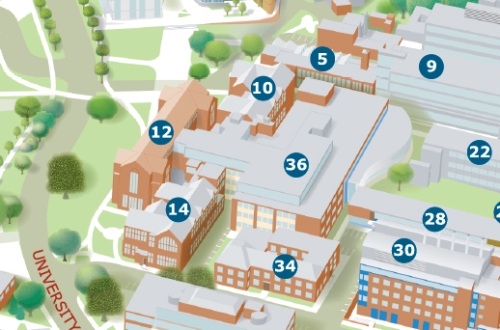

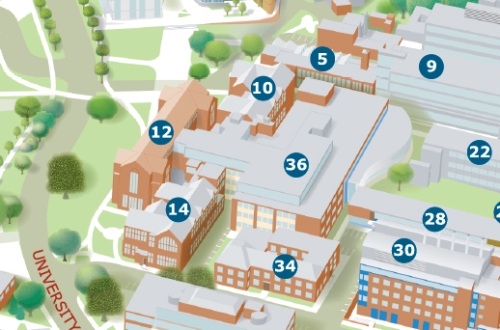

The Hartley Library as it appears on a map of the Highfield campus. The Turner Sims Library is listed as building 12, the Gurney-Dixon Building as building 36, and the wings of the original University building as buildings 10 and 14.

Prior to the 1990s extensions largely focused on accommodation for stock and improving the range of seating available, but from this period increasing attention was being paid to developing workstation and IT provisions in the Library. A small refurbishment project in 1998 saw workstation provisions doubled and a new IT training suite created. The same project saw the south wing of the original 1914 building integrated into the Library.

Further refurbishment projects (2000s-2010s)

Printed collections grew steadily throughout the 1990s and by 2001 the Library was effectively full in terms of stock. By now, the University had grown considerably, as had student numbers, resulting in the need for a major increase in accommodation. Patterns of learning and teaching had also begun to shift with electronic resources growing in importance.

Extension at the rear of the Hartley Library’s Gurney-Dixon Building

The aim of the 2002-4 extension project was to create a research-oriented library that provided a high quality, flexible, study environment, with good quality seating, small study rooms and access to networking. The project saw the largest addition to Library space since the University moved to Highfield. The main elements included new reception, security and help desks; a student-centred foyer; improved access to all floors; increased and improved shelving; and an expansion of space for Special Collections, including a new exhibition gallery. Externally the extensions were a mixture of brickwork, steel framing elements, curtain walling, general glazing and rendered walls.

Since 2004 the Library has undergone further refurbishment, as it continues to develop its services and learning environment. Details on the current Hartley Library Phase 2 refurbishment can be found on the Library website at: http://www.southampton.ac.uk/library/news/2017/03/30-hl-phase2-refurbishment.page

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)