We continue our P-A-L-M-E-R-S-T-O-N series with ‘O’ for Ottoman, as we take a look through Palmerston’s military and diplomatic papers with a focus on the 1840 ‘Oriental Crisis’.

Our first document is a memorandum written by Palmerston in September 1839, recommending actions to be adopted by the British government in response to events that later spiralled into a geopolitical shock that became known as the ‘Oriental Crisis of 1840’:

“19 Sept. 1839

Mehemet Ali [Muhammad Ali, Pasha of Egypt] to be informed that the Five Powers have resolved to support the Sultan [Abdulmejid I – Sultan of the Ottoman Empire] in proposing to him the following arrangement. Mehemet Ali and his male descendants to be appointed by the Sultan hereditary governors of Egypt in the name and under the authority of the Sultan; […] Mehemet Ali to evacuate all the districts and places and parts which he now occupies beyond the limits of Egypt; and to restore the Turkish fleet […].”

MS62/PP/MM/TU/16: Memorandum on measures to be taken against Mehemet Ali, 19 Sep 1839

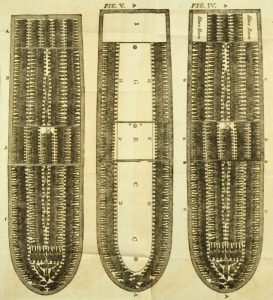

This memorandum was written in the context of the Second Egyptian–Ottoman War (1839–41). Muhamad Ali was nominally only the Ottoman viceroy in Egypt, but since 1805 he had been de facto ruler of Egypt and had been building his own personal power base there for decades. During the earlier Greek War of Independence (1821-9), fought by the Greeks against the Ottoman Empire, Muhammad Ali’s Egyptian forces had come to the aid of the Ottoman Turks and as a reward for this assistance, Ali was promised possessions in Ottoman Syria. When the Ottomans failed to deliver on this, Muhammad Ali’s forces took possession of Syria by force and by 1840 had expanded into other parts of the Middle East and the Mediterranean.

Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia sided with one another to support the Ottomans against Muhammad Ali and his Egyptian forces; collectively they were referred to as the ‘Five Powers’. The European powers had a self-interest in maintaining stability in the eastern Mediterranean and Muhammad Ali’s success in Syria could destabilise the region and even threatened the continued existence of the Ottoman Empire. France and Spain, meanwhile, were sympathetic to Egypt. From 1830 France had been conquering territory in Algeria and was now hoping to increase its influence in north Africa through alliance with Muhammad Ali in Egypt.

In a memorandum written early the following year, Palmerston’s questions on the readiness of British ships in the Mediterranean are answered:

“In answer to Lord Palmerston’s questions on Lord Ponsonby’s despatches nos. 20 and 24, in which Lord Palmerston desires to be informed what instructions have been given to the British Admiral with reference to the contingency of the Egyptian fleet going up to the Dardanelles; the British Admiral has no instructions on that point. And the instructions now in force are sent herewith.

A copy of Colonel Hodges’s despatch reporting reporting Mehemet Ali’s [Muhammad Ali, Pasha of Egypt] intention to go to war near the Dardanelles was sent to the Admiralty on the 14th February.

The combined Egyptian and Turkish fleet will consist of 19 sail of the line, some of them very heavy ships, besides frigates etc., and it appears in the papers that the British fleet in the Mediterranean, after the departure of the Rodney 92 [HMS Rodney (1833)] and Vanguard 84 [HMS Vanguard (1835)] which are stated to be ordered home, will consist of only 10 sail of the line, supposing the Asia 84 [HMS Asia (1824)] is not also ordered home and is stated.

If any instructions on Lord Ponsonby’s despatches are to be sent to the Admiral, they might be conveyed by a Queen’s Messenger who, if despatched tonight, would reach Marseilles in time for the French Packet to Malta of the 1st of March.

February 24 [18]40”

MS62/PP/MM/TU/20: Memo relative to Turkish and Egyptian Fleets, 24 Feb 1840

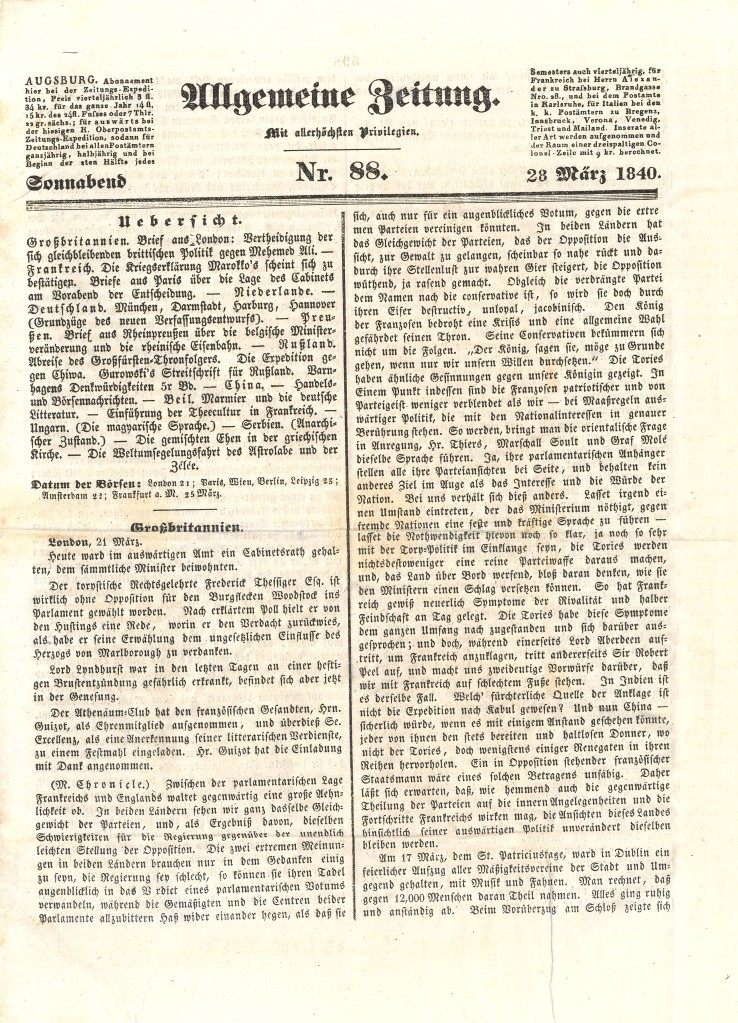

It was not just the threat of instability to trade routes in the eastern Mediterranean that worried Britain and other European powers. Amongst Palmerston’s memoranda on Turkey is a copy of a letter that would be published in an edition of the Allgemeine Zeitung – the leading political daily in Germany in the first part of the nineteenth century:

“Of all the circumstances attending the complications which have for some time past existed in the east of Europe, that which has most surprised us, is the conduct produced by France, for if ever there was a question upon which all good governments in Europe might be expected to unite – cordially together in principle and in action, the Turko-Egyptian question is one.

What is that question? It is neither more nor less than this, first whether a rebellious subject shall be allowed to plunder and finally, to dethrone his lawful sovereign, and secondly, whether for the promotion of his ambitious visions he should be allowed to destroy the balance of power in Europe and perhaps involve the whole continent in a general war. […]”

MS62/PP/MM/TU/21: Letter published in the Allgemeine Zeitung, 14 March 1840

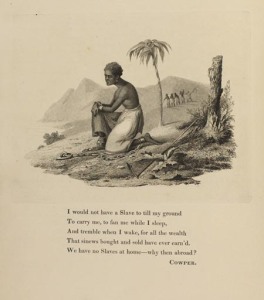

Palmerston’s letter in the Allgemeine Zeitung demonstrates his media savvy, as he engages with the press in order to influence public opinion. In this instance, it was through a German newspaper that Palmerston wished to depict a united front of Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia against the wayward direction France was adopting. In this letter we are given a distinctly negative portrayal of Muhammad Ali, Pasha of Egypt, as a tyrant over his own people and a traitor to his ‘lawful sovereign’ – Abdulmejid I, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Palmerston makes the allegation that Muhammad Ali intended to enslave Greeks during their War of Independence and repopulate their lands with Arabs, in order to elicit high feelings from European newspaper readers against Ali’s conduct; this is despite the fact that the Greeks fought their war against the Ottoman Empire directly.

Abdulmejid I is painted as the victim who has adopted a moderate policy of reform – this is in reference to his Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif, or the “Supreme Edict of the Rosehouse”, which initiated a period of political reform in Turkish history, including promises to guarantee rights to all Ottoman citizens regardless of religion or ethnic group, which Palmerston welcomed in the spirit of liberal constitutional reform. Fear of a wider war and geopolitical instability may have been a sincere concern, but it is interesting that one of the justifications given for resistance to Muhammad Ali’s ambitions was the example it might set in encouraging other subject peoples to rebel against their ‘lawful sovereigns’. Germans or Britons of this period would definitely not have considered a victorious Napoleonic empire over Europe a ‘lawful sovereign’, or indeed the Ottoman Turks as lawful sovereigns over Greece, but imperialism often involves a contradiction, in terms of ‘rights for us, or our friends, but not for them’.

At the same time that Palmerston was busy influencing public opinion he was also working privately behind the scenes, writing to ministers and diplomats, gathering intelligence on the naval prowess of both Muhammad Ali of Egypt as well as the French. In a letter dated 17 April 1840, Palmerston is advised by Lord Minto, First Lord of the Admiralty, on the state of readiness of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, which in the spring of 1840 was not fully manned. Minto advises Palmerston that HMS Vanguard (1835) and HMS Rodney (1833) were not fully manned and that HMS Donegal (1798) is in ‘a very wary condition’.

On 15 July 1840 the Five Powers signed the Convention of London – this offered Muhammad Ali and his heirs continued rule over Egypt, Sudan and the Eyalet of Acre in return for an end to hostilities; the same basic terms as outlined in Palmerston’s memoranda of September 1839.

Muhammad Ali, apparently backed by France, refused this offer but the French subsequently declined to be drawn into open conflict with the other European powers. When Austria and Britain began successful military actions in aid of the Ottomans in September 1840, Muhammad Ali and the Egyptians withdrew from Syria, the Hijaz, the Holy Land, Adana and Crete and handed back the Ottoman naval fleet, which had defected to join the Egyptians in June 1840. Muhammad Ali and his heirs were granted the right to rule over Egypt and Sudan and Ali accepted the Convention of London on 27 November 1840.

![Princess Victoria and her favourite dog [Queen Victoria by Richard R. Holmes, F.S.A, Rare Books Quarto DA 554 1897]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/queen-victoria-with-dog-1.jpg)

![Letter from Queen Victoria to third Viscount Palmerston, British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, 26 Feb 1848 [MS 62 PP/RC/F/350]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/official-letter-from-queen-victoria.jpg)

![Application to Lord Palmerston for appointment of perfumer or hairdresser to Queen Victoria, 2 September 1837 [MS PP/MPC/574]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/letter-requesting-to-be-the-queens-perfumer-2-e1558355061125.jpg?w=500)

![Title page of The Progress of her Majesty Queen Victoria and his Royal Highness Prince Albert in France, Belgium, and England with One Hundred Engravings by William Frederick Wakeman [Rare Books Quarto DA 555]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/third-official-title-page.jpg)

![Letter from foreign diplomat Chevalier de Moiran to his respective court, Counte de la Marguérite, announcing Queen Victoria’s accession, 1837 [MS 62 BR FO/I/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/foreign-diplomat-announcement-of-queen-victorias-accession.jpg?w=627)

![The Queen’s First Council [Queen Victoria by Richard R. Holmes, F.S.A, , Rare Books Quarto DA 554 1897]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/official-queens-first-council.jpg)

![Queen Victoria passing through Ostend, Belgium [The Progress of her Majesty Queen Victoria and his Royal Highness Prince Albert in France, Belgium, and England with One Hundred Engravings by William Frederick Wakeman, Rare Books Quarto DA 555]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/official-carriage.jpg?w=500)

![The form and order of the service that is to be performed, and of the ceremonies that are to be observed, in the coronation of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, in the abbey church of St. Peter, Westminster, on Thursday, the 28th of June, 1838, p.B [Rare Books DA 112]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/form-and-order-of-her-majestys-coronation-e1558354860291.jpg?w=502)

![Form of special service held in St. Mary's church, Southampton, in commemoration of the Jubilee of her Majesty Queen Victoria: June 19th 1887 by St Mary’s Church (Southampton) [Cope cabinet SOU 22]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/southampton-service-for-queen-victorias-jubilee-1887-e1558354799692.jpg)

![An address to the inhabitants of Europe on the iniquity of the slave trade [Rare Books HT 1322]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/oates-book.jpg?w=500)

![Illustration from an album containing anti-slavery tracts and pamphlets, late 1820s [Rare Books HT1163 71-082284]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/rb_ht_1163_illustration.jpg?w=254)

![Illustration of the Duke of Wellington writing the despatches after the Battle of Waterloo, 1815: Illustrated London News, 20 November 1852 [Rare Books quarto per A]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/wellington-waterloo.jpg?w=300)

![Illustration of the funeral procession for the Duke of Wellington passing Apsley House: Illustrated London News, 27 November 1852 [Rare Books quarto per A]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/wellington-funeral.jpg?w=300)

![Illustration of Lord Palmerston making the Ministerial Statement on Dano-German Affairs in the House of Commons: Illustrated London News, 2 July 1864 [quarto per A]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/palmerston-politics.jpg?w=300)

![Lord Palmerston as an elder statesman, West Front, Broadlands: an albumen print probably from the 1850s [MS 62 Broadlands Archives BR22(i)/17]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/palmerston-broadlands.jpg?w=235)

![Item from a collection of deeds relating to property in Petersfield and Mapledurham, principally for ‘Gobyesmede', together with lands in Liss and Sheet, Hampshire [MS 36 AO143]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/ms36_2_a0143-crop.jpg?w=300)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)