Join us in the next three blogs as we explore highlights of the Special Collections exhibition We Protest! which is now closed to visitors due to the Covid-19 outbreak.

In putting together this exhibition we took as its starting point the Cato Street Conspiracy, the bicentenary of which was in February. This so-called “horrible conspiracy” fitted into the pattern of unrest over a range of social, economic and political issues at the end of the eighteenth and start of the nineteenth century, issues that were also to factor in the two other nineteenth-century protest movements that we feature.

The exhibition has proved an opportunity to utilise some little-known material relating to these protests within both the Wellington and Palmerston collections. Pages of notes taken by Lord Palmerston as the Cato Street conspirators were examined before the Privy Council in March 1820 were one such exciting discovery. Whilst the Wellington Archive provided not only samples of handwriting of the conspirators, but a hand-drawn map of the “Swing” riots in Hampshire and amongst the intelligence collected and sent to him about Chartist activity, a fascinating and slightly macabre illustration of the Chartist ‘rising’ in Newport in 1839.

Cato Street Conspiracy

Illustration of Cato Street from a view published in Old and New London (1820)

On 23 February 1820, the Cato Street Conspirators were arrested. This small group, led by the prominent radical Arthur Thistlewood, included individuals from England, Scotland and Ireland, as well as one Jamaican man, William Davidson. Influenced by radical ideas, and responding to repressive measures by the government to previous protests, their aim was to assassinate the cabinet. By this action Thistlewood hoped they would trigger a massive uprising against the government.

Unfortunately for the group, they had been infiltrated by a police spy, George Edwards. The authorities stormed the room at Cato Street and arrested the conspirators. During the fracas Thistlewood shot and killed a policeman.

The Cato Street Conspirators were tried at the Central Criminal Court in London, but as the document below shows also were questioned before the Privy Council. This extract records that Arthur Thistlewood had nothing to say, whilst James Ings expressed a hope that he might be comfortable since he had not previously had “the necessities of life” such as a clean shirt.

Extract of notes taken by Lord Palmerston when Thistlewood and Ings, alongside the other conspirators, were examined before the Privy Council, 1820 [MS62 PP/HA/A/4]

Thistlewood along with James Ings, John Brunt, William Davidson and Richard Tidd were executed on 1 May 1820 after being found guilty of treason; other conspirators were transported.

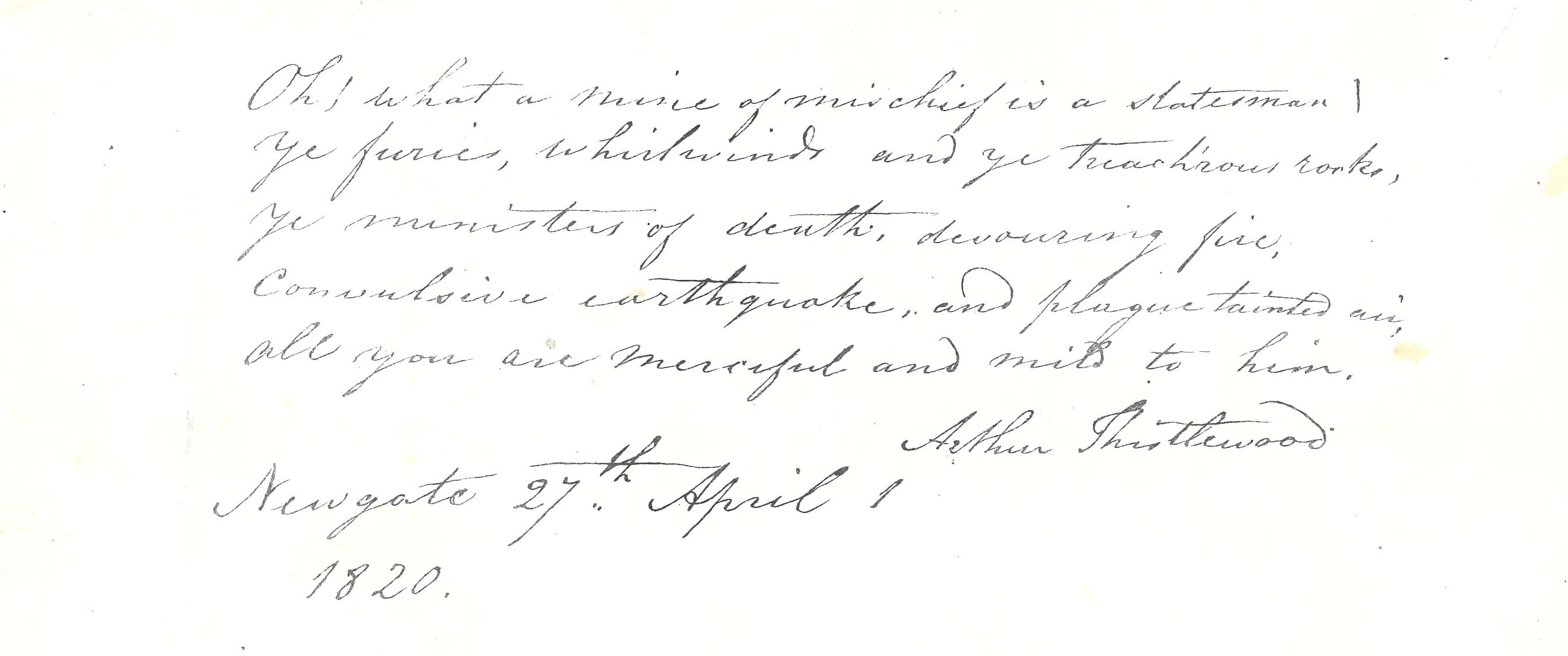

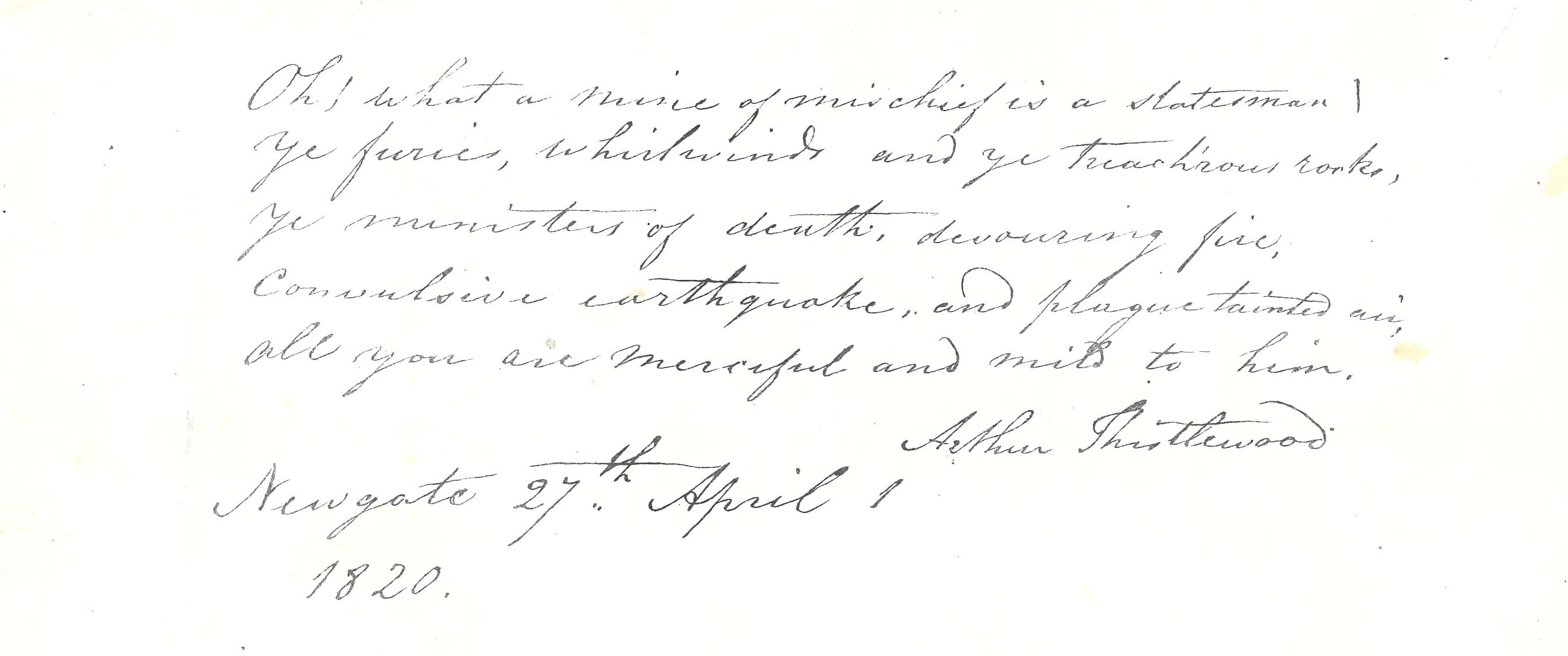

Sample of the handwriting of Arthur Thistlewood, written at Newgate Prison, 27 April 1820 [MS61 WP1/660/1]

“Horrible conspiracy and murder!”: report of the Cato Street Conspiracy in the Gentleman’s Magazine (1820) [Rare Books Per A]

Report from the

Gentleman’s Magazine (1820):

“HORRIBLE CONSPIRACY AND MURDER!

Wednesday, Feb.23.

In consequence of private information received by the Civil Power, that it was in the contemplation of a gang of diabolical ruffians to make an attempt on the lives of his Majesty’s Ministers, whilst assembled at the house of Earl Harrowby, in Mansfield-street, to a Cabinet Dinner, this evening, R. Birnie, Esq. with a party of 12 of the Bow-street patrole, proceeded about eight o’clock to the place which had been described as the rendezvous of these desperadoes in Cato-street, John-street, in the Edgeware-road; where, in a kind of loft, over a range of coach-houses, they were found in close and earnest deliberation. The only approach to this Pandemonium was by a narrow ladder. Ruthven, one of the principal Bow-street Officers, led the way, and was followed by Ellis, Smithers, Surman, and others of the patrole. On the door being opened, about 25 or 30 men were seen within, all armed some way or other; and, for the most part, they were apparently engaged, either in charging fire-arms, or in girding themselves in belts similar to those worn by the military. There were tables about the room, on which lay a number of cutlasses, bayonets, pistols, sword-belts, pistol-balls in great quantities, ball-cartridges, &c. As the Officers entered the room, the conspirators all immediately started up; when Ruthven, who had been furnished with a warrant from the Magistrates, exclaimed, “We are Peace-officers! Lay down your arms!” In a moment all was confusion. A man, whom Ruthven described as the notorious A. Thistlewood, opposed himself to the Officers, armed with a cut-and-thrust sword of unusual length. Ruthven attempted to secure the door; and Ellis, who had followed him into the room, advanced towards the man, and, presenting him pistol, exclaimed, “Drop your sword, or I’ll fire instantly!” The man brandished his sword with increased violence; when Smithers, the other patrole, rushed forward to seize him; and on the instant the ruffian stabbed him to the heart. Poor Smithers fell into the arms of his brother Officer Ellis, exclaiming “Oh God!” and in the next instant was a corpse. While this deed was doing, the lights were extinguished, and a desperate struggle ensued, in which many of the Officers were severely wounded. Surman, one of the patrole, received a musket-ball on the temple; but fortunately it only glanced along the side of his head, tearing up the scalp in its way. The conspirators kept up an incessant fire: whilst it was evident to the Officers that many of them were escaping by some back way. Mr. Birnie exposed himself every where, and encouraged the Officers to do their duty, while the balls were whizzing round his head. At this moment, Captain Fitzclarence (one of the gallant sons of his Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence) arrived at the head of a detachment of the Coldstream Guards. They surrounded the building; and Captain Fitzclarence, with Serjeant Legge and three files of grenadiers, mounted the ladder and entered the room, now filled with smoke, and only illuminated by the occasional flashes of the fire-arms of the conspirators. A ruffian instantly approached the gallant Captain, and presented a pistol to his breast; but as he was in the act of pulling the trigger, Serjeant Legge rushed forward, and whilst attempting to push aside the destructive weapon, received the fire upon his arm. Fortunately for this brave man, the ball glanced along his arm, tearing the sleeve of his jacket from the wrist to his elbow, without wounding him. It is impossible to give a minute detail of the desperate conflict which followed, or the numerous instances of personal daring manifested by the Peace-officers and the military, thus brought into sudden contact with a band of assassins in their obscure den, and in utter darkness. Unfortunately, this darkness favoured the escape of many of the wretches, and the dreadful skirmish ended in the capture of only nine of them. These were instantly handcuffed together, placed in hackney-coaches, and brought down to the Police-office, Bow-street, under a strong military escort; and Mr. Birnie, having arrived at the same moment, instantly took his seat upon the Bench, and prepared to enter into the examination of the prisoners. They were immediately placed at the bar in the following order:- James Ings, a butcher; James Wilson, a tailor; Richard Bradburn, a carpenter; James Gilchrist, a shoemaker; Charles Cooper, a bootmaker; Richard Tidd, a bootmaker; John Monument, a shoemaker; John Shaw, a carpenter; and William Davidson, a cabinet maker.

Davidson is a man of colour, and a worthy coadjutor of Messrs. Watson, Thistlewood, and Co. upon many occasions. At the meeting in Finsbury market-place a few months ago, he was one of the principle speakers.

Ings is a hoary ruffian, a short squat man, apparently between 50 and 60, but of most determined aspect. His hands were covered with blood; and as he stood at the bar, manacled to one of his wretched confederates, his small fiery eyes glared round upon the spectators with an expression truly horrible. The rest had nothing extraordinary in their appearances. They were for the most part men of short stature, mean exterior, and unmarked physiognomy.

The office was crowded with soldiers and officers, bringing in arms and ammunition of various kinds, which had been taken on the premises; muskets, carbines, broadswords, pistols, blunderbusses, belts, and cartouch-boxes, ball-cartridges, gunpowder (found loose in the pockets of the prisoners), haversacks, and a large bundle of singularly-constructed stilettoes. These latter were about 18 inches long, and triangular in form; two of the sides being concave, and the other flat; the lower extremity having been flattened, and then wrung round spirally, so as to make a firm grip, and ending in a screw, as if to fit into the top of a staff. Several staves indeed were produced, fitted at one end with a screwed socket; and no doubt they were intended to receive this formidable weapon.

The depositions of a number of officers, most of them wounded, and several of the soldiers, having been taken, their evidence substantiating the foregoing narrative, the prisoners were asked whether they wished to say any thing. Cooper and Davidson the black were the only ones who replied; and they merely appealed to the officers and soldiers to say, whether they had not instantly surrendered themselves. Ellis, the patrole, who received the murdered body of his comrade Smithers in his arms, replied, that Davidson made the most determined resistance. At the moment when the lights were extinguished, he had rushed out of the place, armed with a carbine, and wearing white cross-belts. Ellis pursued him a considerable distance along John-street, and, having caught him, they fell together; and, in the deadly struggle which ensued, Davidson discharged his carbine, but without effect, and Ellis succeeded in securing him.

Capt. Fitzclarence had seized and secured one or two of the prisoners with his own hands; and he was not only very much bruised, but his uniform was almost literally torn to pieces.

At eleven o’clock, the deposition having been taken, as far as the circumstances of the moment would permit, the Magistrate committed the prisoners for further examination on Friday; and they were then placed in hackney-coaches, two prisoners being placed in each coach, accompanied by two police officers, with two soldiers behind and one on the box, and the whole cavalcade escorted by a strong party of the Coldstream Guards on foot.

The following morning an extraordinary Gazette was issued, offering 1000l. for the apprehension of Arthur Thistlewood. He was taken by Bishop and a party of police officers, about 12 o’clock the same day, at No. 10, White-street, in Little Moor fields.

The house is kept by a person named Harris, who is foreman to a letter-founder; at the time of the apprehension Harris was from home, and supposed to be at his work; but the offices took his wife with them to Bow-street. The house is full of lodgers; none of whom were aware of Thistlewood being on the premises till the officers entered; nor was he ever seen there before.

The following are circumstantial particulars of Thistlewood’s arrest. At 9 o’clock in the morning, Lavender, Bishop, Ruthven, Salmon, and six of the patrole, were dispatched; and, arriving at the house, three of the latter were placed at the front, and three at the back door, to prevent escape. Bishop observed a room on the ground floor, the door of which he tried to open, but found it locked. He called to a woman in the opposite apartment, whose name is Harris, to fetch him the key. She hesitated, but at last brought it. He then opened the door softly. The light was partially excluded, from the shutters being shut; but he perceived a bed in a corner and advanced. At that instant a head was gently raised from under the blankets, and the countenance of Thistlewood was presented to his view. Bishop drew a pistol, and presenting it at him, exclaimed, ‘Mr. Thistlewood, I am a Bow-street officer; you are my prisoner:’ and then, ‘to make assurance double sure,’ he threw himself upon him. Thistlewood said, he would make no resistance. Lavender, Ruthven, and Salmon, were then called, and the prisoner was permitted to rise. He had his breeches and stockings on, and seemed much agitated. On being dressed, he was handcuffed. In his pockets were found some ball-cartridges and flints, the black girdle, or belt, which he was seen to wear in Cato-street, and a sort of military silk sash. A hackney coach was then sent for, and he was conveyed to Bow-street. In his way thither he was asked by Bishop what he meant to do with the ball cartridges? He declined answering any questions. He was followed by a crowd of persons, who repeatedly cried out, ‘Hang the villain! Hang the assassin!’ and used other exclamations of a similar nature. When he arrived at Bow-street, he was first taken into the public office, but subsequently into a private room, where he was heard unguardedly to say, that ‘he knew he had killed one man, and he only hoped it was Stafford,’ meaning Mr. Stafford, the Chief Clerk of the office, to whose unremitting exertions in the detection of public delinquents too much praise cannot be given. Mr. Birnie, having taken a short examination of the prisoner, sent him to Whitehall, to be examined by the Privy Council. Here the crowd was as great as that which had been collected in Bow-street. Persons of the highest rank came pouring into the Home Office, to learn the particulars of what had transpired. The arrest of Thistlewood was heard with infinite satisfaction he was placed in a room on the ground floor, and vast numbers of persons were admitted in their turn to see him. His appearance was most forbidding: his countenance, at all times unfavourable, seemed now to have acquired an additional degree of malignity: his dark eye turned upon the spectators as they came in, as if he expected to see some of his companions in guilt, who he had heard were to be brought thither. He drank some porter that was handed to him, and occasionally asked questions, principally as to the names of the persons who came to look at him. Then he asked, ‘To what gaol he should be sent? – he hoped not to Horsham.’ (This was the place in which he was confined in consequence of his conviction for sending a challenge to Lord Sidmouth.)

At two o’clock he was conducted before the Privy Council. He was still handcuffed, but mounted the stairs with alacrity. On entering the Council-chamber he was placed at the foot of the table. He was then addressed by the Lord Chancellor, who informed him that he stood charged with the twofold crime of treason and murder, and asked him whether he had any thing to say for himself? He answered, that ‘he should decline saying any thing on that occasion.’ He was then committed to Coldbath-fields prison.

The other prisoners, apprehended the night before, were likewise taken before the Privy Council, and recommitted. In addition to the Cabinet Ministers, there were present, Viscount Palmerston, the Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer of Scotland, Sir William Scott, Mr. Sturges Bourne, the Attorney and Solicitor-General, Sir John Nicholl, &c. They continued in examination of the prisoners till past six o’clock, when the prisoners, who had been kept in separate rooms, were removed in hackney-coaches to the House of Correction, escorted by a party of the Life Guards, amidst the execrations of those assembled round, and Thistlewood was loudly hooted and groaned at when he was taken from Bow-street Office.

In the course of the day, further arrests took place. Among others secured is a man of the name of Brunt – who is stated to have been second in command to Thistlewood. He was apprehended at his lodgings in Fox-court, Gray’s-inn-lane; in his room a vast quantity of hand-grenades, and other combustibles, were found. These were charged with powder, pieces of old iron, &c., calculated, upon explosion, to produce the most horrible consequences. A great number of pike-blades, or stilettoes, such as were discovered in Cato-street, and a number of fire-arms, were likewise found. The whole of these, together with the prisoner, were taken to Bow-street. He was afterwards sent to Whitehall, and then committed to Coldbath-fields.

Firth, the person by whom the stable was let to Harrison, has likewise been arrested. He admits that he has attended some of the Radical meetings, but denies any knowledge of the conspiracy. Warrants have been issued for securing six others, whose names and descriptions are known.

John Harrison, who hired the room in Cato-street, was apprehended in his lodging in Old Gravel-lane. He was 10 years a private in the Life Guards, from which he was discharged about six years ago.

Robert Adams, who had been five years a private in the Oxford Blues, and Abel Hall, have also been taken. Adams is a middle-aged man, and of respectable appearance.

The lodgings of Thistlewood, and of all the others who were in custody, have been searched, and several important papers, and quantities of arms, have been discovered and seized.

It is a singular fact, that when Thistlewood was arrested, he had not a farthing of money in his possession. The same observation may be made with respect to his comrades, all of whom were in the most wretched state of poverty.

A man was apprehended by Taunton and Maidment, charged with making handles for the pikes which were seized at the stables. He was committed for further examination.

Wm. Symmonds, a footman, at No. 20, Upper Seymour-street, was apprehended by Lavender and Bishop, charged on suspicion of being concerned with the assassins. He is suspected of giving them information respecting the transactions of the higher orders. He was detained.

Since obtaining the preceding intelligence, the following particulars have been received: –

A detachment of thirty of the Cold-stream Guards was ordered from Portman-street Barracks a quarter before eight o’clock (the men thought it was to attend a fire); Captain Fitzclarence headed them. On coming into the neighbourhood of Cato-street, Capt. F. commanded them to halt and fix bayonets, and every man to be silent. Almost immediately afterwards they heard the report of a pistol: they were instantly commanded to advance in double quick time, upon the spot from whence it proceeded. On reaching the stable, a man darted out and was making off, but was prevented: finding his retreat intercepted, he pointed a pistol at Captain Firzclarence; Serjeant Legge broke his aim knocking the pistol off at the instant of its discharging, and was thus himself wounded in the right arm; the man was then secured. The Captain then ordered the men to follow him into the stable; their entrance was opposed by a black man, who aimed a blow at Captain F. with a cutlass, which one of his men warded off with his firelock: he exclaimed, “Let us kill all the red-coats; we may as well die now as at any other time;” he was also secured. They then entered the stable. Captain F. being first, was attacked by another of the gang, who pointed a pistol, which flashed in the pan: the soldiers took him likewise, to whom he said, “Do’nt kill me, and I’ll tell you all about it.” The soldiers then mounted into the loft; there they found the body of the murdered officer, and another man lying near him; the latter, who was one of the gang, was ordered to rise; he said, “I hope you will make a difference between the innocent and the guilty. Don’t hurt me, and I’ll tell you how it happened.” Five more were then secured, one of whom declared he was led into it that afternoon, and was innocent.

Davidson was one of those who, at the last meeting in Smithfield at which Hunt presided, paraded the streets of the metropolis with a black flag, on which was described a death’s head.”

Although the Cato Street Conspiracy was used by the government to justify the Six Acts of Parliament that it had passed two months previously — dealing with groups training with weapons, mass meetings, sedition and libel — this did not mark the end of protest for causes in the subsequent decades of the nineteenth century as we shall see.

The “Swing” riots

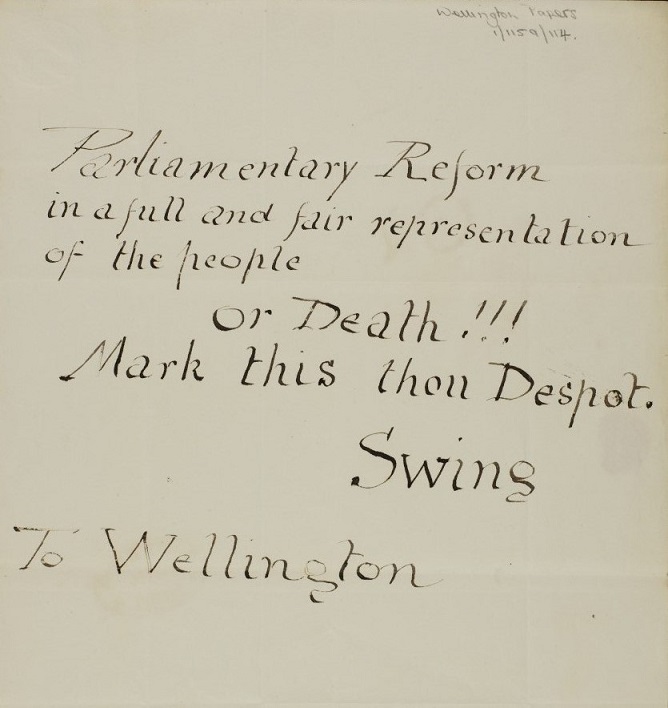

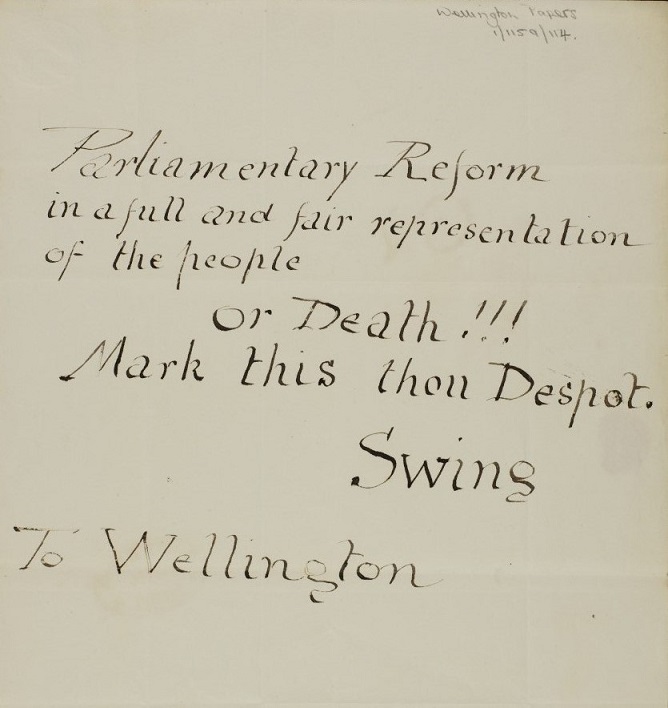

The “Swing” riots of 1830-1 saw agricultural workers protesting about low wages and the inadequate Poor Law allowances that were used to supplement these wages, as well as the use of threshing machines which they felt threatened their livelihood. Labourers became desperate and resorted to poaching to try and feed their families, leading to an increase in crime rates. William Cobbett had recorded in his Rural Rides his horror at the state of the rural poor in Hampshire, which had a sizeable population of agricultural labourers on subsistence wages. And Hampshire was one of the counties where these riots were most severe. It was also where the riots were most severely punished, as the Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire, the Duke of Wellington, was determined to crush any unrest. One of the particular characteristics of these riots was the threatening letters signed by “Captain Swing” sent to all landowners in Hampshire, including Wellington, an example of which is below.

Letter signed by “Captain Swing” to the Duke of Wellington threatening assassination, n.d. c.November 1830 [MS61 WP1/1159/114]

The alarm felt by the Hampshire gentry at the prospect of riots is illustrated in a letter from Henry Holmes, Romsey, to Lord Palmerston of 21 November 1830. Lord Palmerston was, of course, another Hampshire landowner and resident of Romsey.

“Your Lordship is of course aware that the country is in a very disturbed state generally…. We are (thank God) quiet as yet in this immediate neighbourhood, but when we see in several parts of this, and adjoining counties, frequent acts of outrage committed and know that a seditious spirit is openly exhibited almost everywhere, we think it proper to call your Lordship’s attention to the subject, and take the liberty of enquiring whether your Lordship thinks it probable that his Majesty’s Government will adopt any general measures for the preservation of the peace….

In the neighbourhood of Andover much mischief has been done as your Lordship will see by the papers. I have just had a man with me who saw the mob break open the gaol and rescue a prisoner.

I had written thus far this morning, when I was interrupted by my man servant whose father had left the mob at Compton near Kingsomborne, where they broke the thrashing machines of Mr. Edwards and extorted money and drink. They had previously attacked Mr Penleazes’ House at Bossington and Mr. Edwards’s at Horsebridge. I sent my son on horseback to reconnoitre – he arrived at Kingsomborne just as they had passed for Ashley. Mr Lutott is just arrived from London – he saw Sir William Heathcote and Mr. Stanley go from Winchester with a troop of cavalry towards Crawley which is not far from Ashley. We are swearing in special constables here, and I have conferred with Watson as to being prepared to defend Broadlands if it should be attacked – but as the troops are on the alert I dare say the mob will be dispersed.

If Government would let us have the old arms and accoutrements of the yeomanry we would equip a troop and act in concert in case of necessity – as it is we are almost defenceless, but if they come here I trust we shall be able to make a fight, and keep down our own disaffected who are very numerous I am sorry to say.”

[MS62 BR113/12/29]

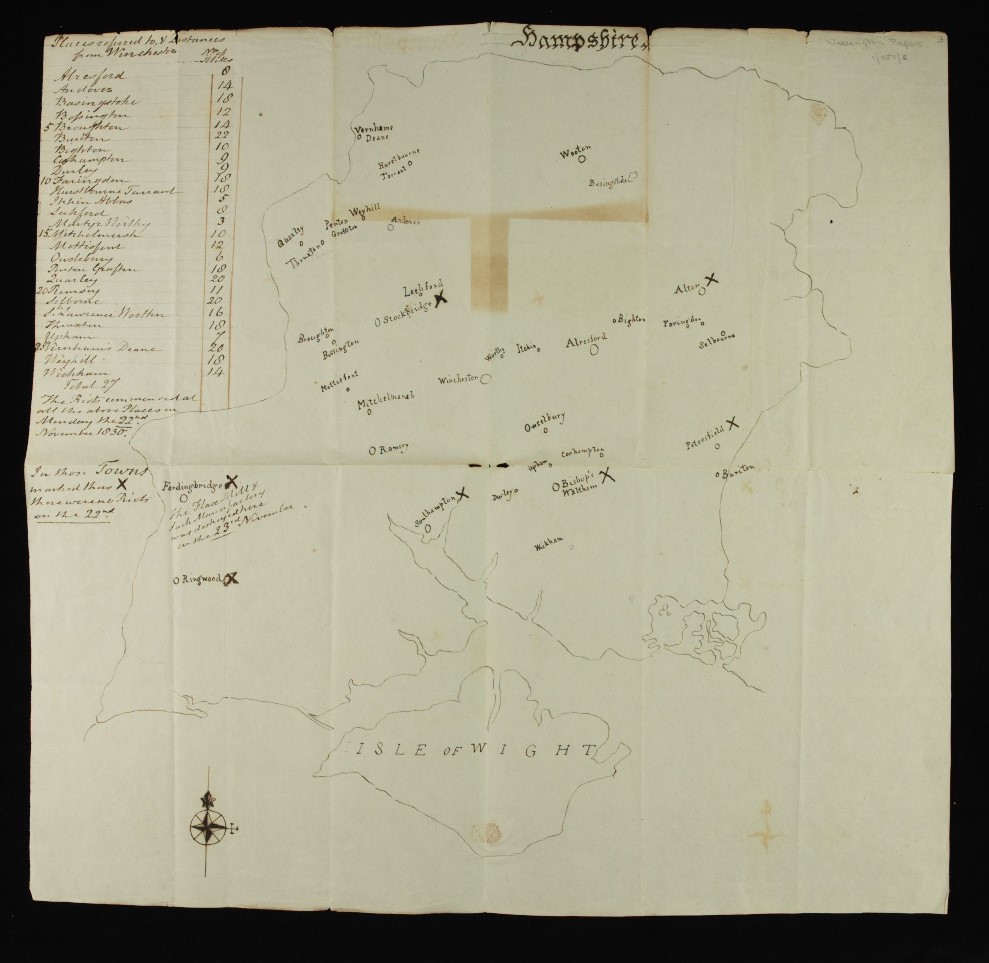

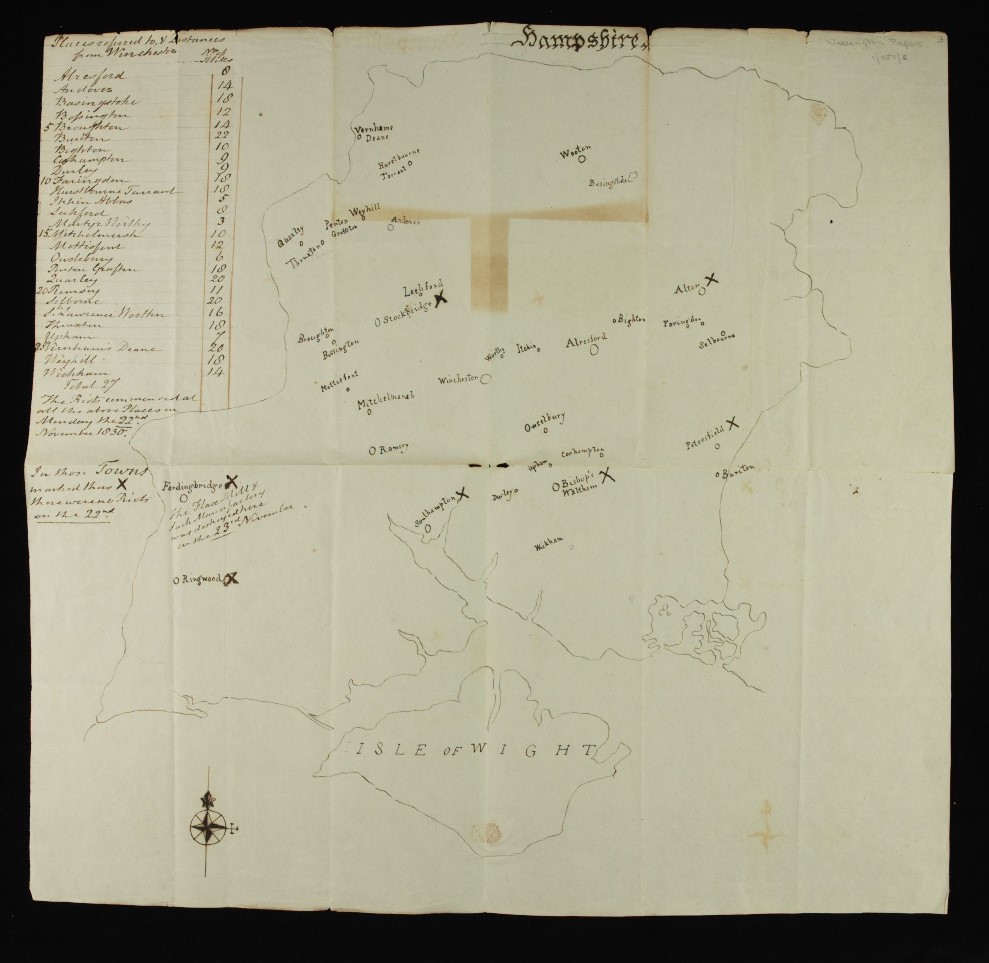

The extent of the rioting that took place across the county on 22 November is illustrated in a hand drawn map sent to the Duke of Wellington:

Hand drawn map showing instances of riots across Hampshire, 22 November 1830 [MS61 WP1/1157/2]

Over three hundred men who had been involved in these riots were tried before the Special Commission at Winchester in December 1830. Despite over ninety men being sentenced to death, only two executions were carried out, those of Henry Cook of Micheldever, convicted of riot, robbery and aggravated assault and James Thomas Cooper of Fordingbridge, convicted of destroying machinery and a manufactory at Fordingbridge. Sixty-nine of the prisoners received prison sentences and a further sixty-eight were transported to Australia.

Copy of a letter from the Duke of Wellington, to Lieutenant General Sir Herbert Taylor, sets out the result of the trials, 30 December 1830

There were 98 capital convictions. Of these the law has been allowed to take its course in relation to six. Three of them concerned in the destruction of manufactories aided by machinery, one in the destruction of poor houses, one for a robbery by night, one for a robbery by day – this last is the man who struck Mr. Baring. It will be recommended that the others should be transported for life.

Several have been sentenced during the commission to transportation for life, and some for terms of years. But this morning twenty were sentenced to transportation for seven years, and ten to confinement and hard labour from twelve to eighteen months for destroying machines.

Upon the whole this commission has worked well, and has already produced a good effect and I hope that its consequences will be long felt.

It is very curious that throughout these trials we have scarcely heard of distress. Few of the people convicted have been agricultural labourers. They are generally publicans and mechanics. Of those left for execution, one was a hostler at an inn, another a publican, two blacksmiths, one carpenter and one bricklayer.

[MS61 WP4/2/2/58]

Chartists

The Chartist movement, which could claim to be the first mass movement driven by the working classes, grew out of the failure of the Reform Act of 1832 to extend the vote beyond the property owning classes. In 1838, a People’s Charter was drawn up for the London Working Men’s Association and this was presented to Parliament in June 1839. Its rejection led to unrest across the country, which was quickly and harshly dealt with by the authorities.

The Duke of Wellington was one of the members of the government who received intelligence on possible unrest and within his archives are examples of intercepted letters from Chartist activists. The following is a copy of a letter from a leading Chartist in the north which were passed on to the authorities by “one of the converted Chartists”, since he was concerned “that bloody scenes would soon break out in the middle and north of England, to the disadvantage of the operatives and the ruin of the country”.

Copy of a letter from an unnamed Chartist to Mary Anne, 6 December 1839

“My dear Mary Anne,

You are the prince of correspondents but [f.9r] I do not wish you to do so again unless you think it of importance and above all do not put even your initials, but take another name altogether as the name of the town is sufficient and I know your writing and allusions. Put any name you like but your own and write it at full length, as initials are suspicious should the letter be opened and I do not wish you to be brought into scrapes. I must see our friend, who is ill, at all hazards and that right soon, so, as early as you lay hands on him tell him to put himself in communication with me by letter addressed as your last. Matters are coming to a crisis and that in short space. Most shall not be tried or will have companions he little thinks of; keep this in mind and be astonished at nothing. Depend upon it there will be a merry Christmas. All here are already preparing for a national illumination, I presume in anticipation of the Queen’s marriage, but you know best. These [f.9v] Radicals are humble fellows; at least half a dozen emissaries have been sent to see what state the north of England was in and the universal feeling is that there is no county like [blank]. This is partly to be attributed to the vast extent of moorland which has generated a race of hardy poachers, all well armed and who would think themselves disgraced if they missed a moorcock flying seventy yards off. This, together with the number of weavers necessarily in want has made a population ripe for action, and its neighbourhood, to the Scottish border, with the facilities for a guerilla warfare are said to have determined [blank] to make it the headquarters for a winter campaign. That he is mad enough to attempt this you will easily believe even if there was no other movement in England because, from the feeling of the people towards him, they would follow him to the death and England has not troops [f.10r] enough to quell a border riot with that man at its head. It is too far away, however, to have any effect for a long time…..

[MS61 WP4/10/66 ff.8v-10r]

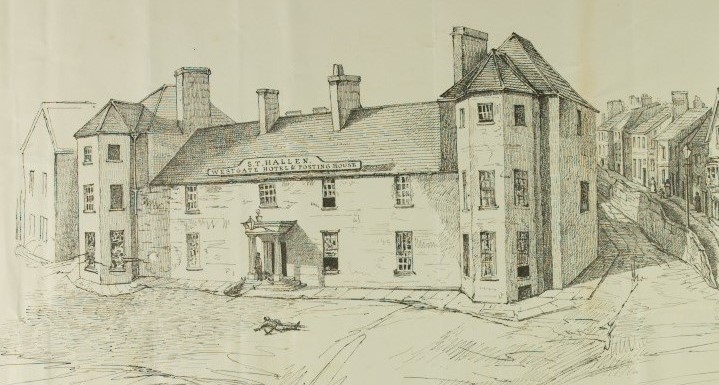

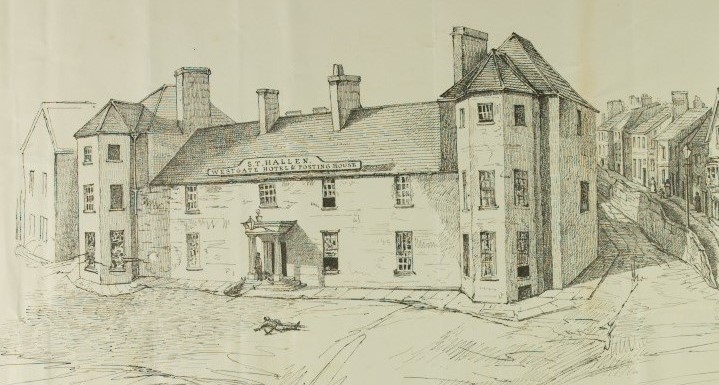

Wellington likewise received information about the ‘rising’ in Newport in November 1839 which saw thousands of armed Chartists march on the town. In this violent clash at the Westgate Hotel, an estimated twenty two Chartists were shot dead and many more were injured. It has been called the most serious manifestation of physical force Chartism in the history of this movement.

Illustration of the attack and defence of the Westgate Hotel, Newport, November 1839 [MS61 WP2/64/74]

Illustration of the ground plan of the Westgate Hotel, Newport, showing the position of the 45th Regiment defending the building and of fatalities from the battle, November 1839 [MS61 WP2/64/74]

The illustration of the Westgate Hotel includes images of the soldiers firing from a downstairs window to defend the property. Below it is a ground plan of the hotel which includes pikes to show the points where the Chartists entered the building, firelocks to show the points where the 45

th Regiment defended the building and there are stick figures on the plan showing as near as can be ascertained where individuals died.

For our next blog we shall be moving on to protests in the twentieth century and looking in particular at the “Battle of Cable Street”. We hope you can join us.

!["Highcliffe in Hampshire" drawn by Callander, 1784 [Cope Collection]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/cq_hih_72r_0003-2.jpg)

![Map of the county around Southampton for John Bullar (1819) [Cope Collection]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/cope04_bullar52_293007_0011-2.jpg)

![Broadlands printed by Ackermann [Cope Collection]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/cq_72_bro_pr_41_0005-2.jpg)

![Lithograph of Paultons, [c.1830] [Cope Collection]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/cq72paur_0003-2.jpg)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)