Welcome to the third in our “behind the scenes” blogs where we shift focus to the work of Conservation and a project relating to the Broadlands Map Collection, part of the Broadlands Archive (MS62).

The Broadlands Map Collection consists of over 220 maps and plans from the mid 18th century to the mid 20th century. There is a wide range of media used, including pencil, iron gall ink, watercolour, printers ink and red India ink. The challenge of conserving this wonderful series is the range of media: the earlier maps are on vellum, with others on handmade paper, tracing paper, linen and finally machine made paper. The collection also includes very large items (2278mm x 478mm).

What all this material had in common was that they required cleaning, were tightly rolled and they had rips, tears and in some cases structural loss with general degradation.

The initial part of the conservation project was to survey the collection. From this survey a number of recommendations were highlighted, for the cleaning of the items, for the repair of small tears, and for the requirements of flat storage for ease of access.

Dry cleaning was undertaken with chemical smoke sponges and cosmetic sponges and then each item was placed between blotters with ever increasing weights to carry out dry flattening. Whilst items were undergoing this lengthy procedure a decision was made to explore the possibility of carrying out aqueous cleaning of the architectural watercolours and MBMAP57 was chosen as a test subject. Conservator Sonia Bradford talks about this work below.

The Broadlands map survey identified that several architectural watercolours not only needed cleaning, but being tightly rolled and in some cases damaged, were not easily accessible. These items were initially dry cleaned with chemical and cosmetic sponges and left to gently flatten between clean blotters under increasing weights since July 2017. After two years of flattening the watercoloured items were assessed with the following conclusion:

- They were still curled and difficult to handle

- They still contained ingrained dirt

- The pH of the stiff paper was acidic

Aqueous treatments would address the above problems, however the correct treatment would need to be carried out to avoid any detrimental or permanent damage to the object. As a result of this four watercolours were chosen to undergo various controlled aqueous treatments to ascertain the best course of action for the remaining collection. Below is a summary of the investigation and final results obtained to carry out successful conservation of this lovely collection. BRMAP57 consists of 4 elevation views of a proposed design of the bailiffs house at Broadlands. (N.E.S. & W) – they are of the same size, paper and watercolour palette.

Fugitivity of the inks were spot tested with water and all results including the red line border were clear.

Humidification using a Cedar Box

The North (N) and East (E) views were placed in a cedar humidification box consisting of a layer of wet fleece placed on the Corian® studio table, then Gortex® (shiny side up), the object (with the illustration side up) and the glass top placed on the cedar box.

The documents were still heavily curled and therefore glass weights were placed at each end to hold the item in place until the humidification had sufficiently relaxed the paper. Unfortunately the pressure of the glass weights led to increased water absorption in that area and tide lines were beginning to form. Due to this, the objects immediately underwent a blotter wash to eliminate any permanent tide lines and take advantage of the paper in a relaxed state.

Blotter Wash

A series of controlled blotter washes were set up for the North and East views to remove ingrained dirt and the possibility of reducing acidity.

Felt was placed on the Corian® studio table with a layer of Melinex® to protect the felt. 2 x wet blotters and 1 x damp blotter placed on the Melinex® followed by the object (illustration side up). Thin Bondina® (17gsm), to protect the document and a perspex weight if appropriate.

If the object dried out too much the object was mist sprayed, and as discolouration appeared on the damp blotter this was replaced. pH tests were carried out throughout the process as the documents were now wet enough to use pH test strips (2.0 – 9.0)

1st Blotter 2nd blotter

North View 4.3 4.4

East View 4.3 4.4

Fugitivity of particularly the red border line was checked using a digital microscope during the washing process. There was no reaction/movement to the red line during the blotter wash.

Both documents continued to absorb moisture unevenly on the damp blotter and a decision was made to spray both papers until wet through and then re-placed on the damp blotter for impurities to be pulled through. This was achievable due to the stability of the watercolours/inks.

After half an hour the wet blotters were saturated with tap water again and the damp blotter changed for a new one. Quite a lot of discolouration (especially the left band of the North view) had pulled through onto the damp blotter.

After the first blotter wash it was decided to remove the felts and to only use the Corian® work tables as a base to give an even contact and increased pressure with the damp blotters and a Perspex sheet on top of the Bondina® protective layer. The second blotter was left for 1 hour with fugitivity tests being carried out and a pH test completed at the end of the wash.

The second blotter wash showed more discolouration due to the flat surface contact and increased pressure from the perspex sheet.

If no further treatment was to be carried out, I would replace the damp blotter for a third time/until no further discolouration of the damp blotters.

Float Wash

A white photographic tray placed on a flat surface and filled to a third with cold tap water (almost pH neutral).

The object was placed on thin Bondina® and a dahlia spray mist to relax the object. The Bondina® and object (image side up) lifted up and placed or ‘floated’ on the water in the tray.

Small pieces of thin blotter were prepared for use in case of any water ‘pooling on the surface’. Cold water float wash carried out for 15 minutes and then the water changed for a second cold water float wash. Once the water showed discolouration it was changed. The red margin line was still stable with no movement therefore a warm float wash (approx. 30oc) was carried out for 15 minutes.

N.B. the object should be spray misted if it becomes dry or if water pools on the surface of the object thin blotter strips can remove the excessive water.

3 x cold float wash 1 x warm float wash

pH after 3rd wash pH after warm wash

North View 6 6.1

East View 7 7

The objects were left to air dry on Bondina® and blotter overnight. If no further treatment were to be undertaken then the objects would be dried gradually with new blotters under a Corian® board to ensure even flattening.

Full Immersion Wash

Both North and East views were fully immersed on Bondina® supports in cold water for 15 minutes in a white photographic tray.

The full immersion wash is an effective way of ‘washing away’ any remaining impurities/dirt/acidity.

An alkaline buffer wash was discussed but not carried out for two reasons;

- A large proportion of acidity had been washed out during the various washes and a further alkaline wash would not particularly benefit the pH enough to carry out a 30 minute buffer wash.

- More importantly it was decided not to compromise a possible ‘colour change’ from the alkaline buffer due to the reaction it can cause with watercolours.

Full Immersion wash (pH test strip)

North View 7.5

East View 7.5

Results

The Humidification process was time consuming, lengthy to set up and due to the uneven moisture absorption the treatment was adapted midway (by spraying the paper until wet through)

The blotter washes again took a period of time to set up and carry out, this would be even longer if doing repeated blotter changes until no further discolouration appeared on the damp blotter. This was the first opportunity to carry out a pH reading and even after the second blotter the reading was still highly acidic at pH 4.4

The advantage of the blotter wash was the controlled element of the treatment. Due to minimum water being absorbed, but a strong ‘pull’ of discolouration impurities the object could be successfully cleaned and a low risk of damage/fugitive inks/colour change becoming a problem as the object could be easily retrieved and dried at any given point.

This would be an effective treatment if the document showed an acceptable pH level or if the document needed to be carefully monitored due to fragility/suspect fugitivity or any other reason where the procedure may need to be stopped immediately.

The float washes appear to have been effective partly because they removed a significant amount of discolouration from the object, however the pH acidity didn’t effectively change from the first blotter reading. If carrying out aqueous treatments on several documents I think that a 90 minute – 2 hour float wash would not only remove a substantial proportion of discolouration but would also improve the pH reading as the float washes were fairly short in the tests. The float wash also gives a level of control during the process and a full immersion wash can still be carried out if desirable.

Full immersion wash proved the most effective in ‘washing out’ acidity with the most improved readings and leaving the document with an acceptable neutral pH level. The water didn’t show any discolouration, but this is probably due to the fact that the item had already undergone multiple washes.

South and West Views

Due to the lengthy set up and process of the humidification cedar box and the various blotter washes and the disappointing results of the pH readings these processes were omitted and the objects were mist sprayed and float washed. The controlled washing on the North and East views had proven that the watercolour media was stable and that these two views were unlikely to react any differently. The float wash still being a controlled method of aqueous washing.

Aqueous Treatment

Both the South and West views were float washed in exactly the same way as the North and East views (see earlier). The only difference being that the items were float washed for 90 minutes and the surface of the object was mist sprayed where appropriate. A full immersion cold wash for 20 minutes was also carried out.

pH Tests

Before treatment After float wash After full immersion

South View

4.3 6.3 7

West view

4.4 6.4 7.5

Conclusion

1. The continuous testing and controlled aqueous treatments of these watercolours has ensured that the colours and margins have not been affected. The results of the float washes and full immersion wash has significantly reduced the acidity to an acceptable neutral pH.

2. A further advantage is the object is now flat rather than tightly rolled. Several of the objects in the collection have suffered large rips and damage/detachment of tabs and map inserts from being rolled and un-rolled unprofessionally – before becoming part of the Special Collections!

3. Repairs can be carried out whilst still wet including large tears or weakened areas being lined with spider tissue and wheat starch paste.

4. Objects can be used for exhibitions without requiring substantial weights to combat curled and rolled items. Much lower risk of damage whilst handling flattened and repaired documents.

5. The objects can be stored flat between acid free tissue in archival boxes keeping them appropriately preserved with easier access for both curators and researchers who need to handle them.

We hope that you have found this glimpse into the work of the conservation section of interest. Do look out for our other behind the scenes blogs.

![Nagasaki, Japan, 1881-2 [MS 62 Broadlands Archives MB2/A20]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/nagasaki_japan_1881-2_ms62_mb2_a20_2.jpg)

![The English Quarter, Shanghai, China [MS 62 Broadlands Archives MB2/A20]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/shanghai_china_1881_ms62_mb2_a20.jpg)

![Samurai practising with double-handed swords, Japan 1881 [MS 62 Broadlands Archives MB2/A20]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/samurais_and_swords_japan_1881_ms62_mb2_a20.jpg)

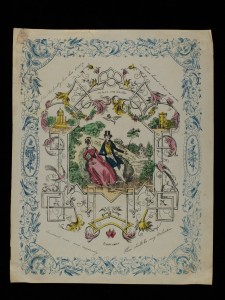

![Programme for the Singapore Races, Autumn 1880 [MS64/292]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/singaporeraces_autumn1880_ms64_292.jpg?w=196)

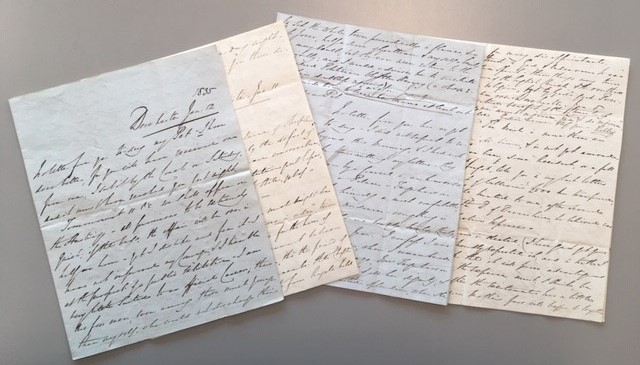

![A draft of a report on the defences of Singapore, from Parnell’s papers as president of the Singapore Defence Committee, with his annotations and notes on business [MS 64/291]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/report_upon_further_defences_of_singapore_jan1880_ms64_291.jpg)

![Section from the Journal of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Parnell, describing is trip to Japan in September 1883 [MS 64/278]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/journalofparnell_japan_sept1883_ms64_278.jpg)

![Singapore: the route to Government House lined by head hunters (Dyak tribesmen) from Borneo, March 1922 [MS 62 Broadlands Archives MB2/N7, 187]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/ms62_mb2_n7_p47_187.jpg)

![Unveiling of the Straits Settlements War Memorial, with the Prince of Wales’ staff on the right, March 1922 [MS 62 Broadlands Archives MB2/N7, 189]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/ms62_mb2_n7_p48_189.jpg)

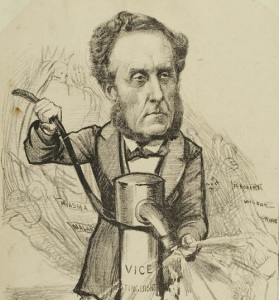

![Lord Shaftesbury [MS 62 SHA/MIS/55]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/ms62_sha_mis_55.jpg?w=216)

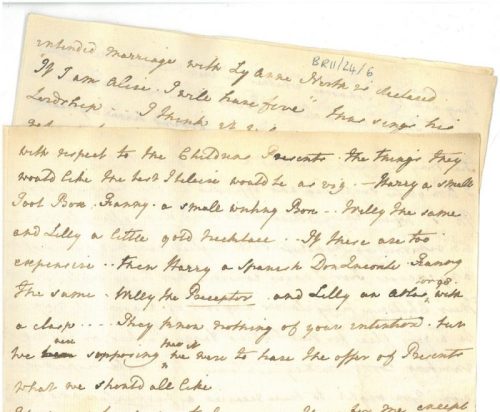

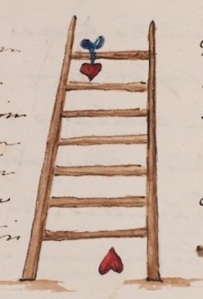

![Poem written by Lord Shaftesbury’s sister for Lord Shaftesbury for his eight birthday [MS 62 SHA/MIS/62]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/ms62_sha_mis_62.jpg)

![Lord Shaftesbury, October 1858 [MS 62 SHA/MIS/49]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/ms62_sha_mis_49.jpg?w=183)

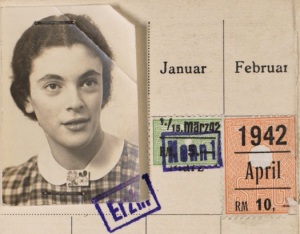

![Lady Emily Cowper, wife of Lord Shaftesbury [MS 62 SHA/MIS/61]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/ms62_sha_mis_61.jpg?w=205)

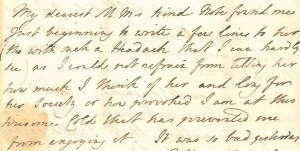

![Lord Shaftesbury's diary entry for February 20th 1828 [MS 62 SHA/PD/1, p.36]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/official-ms-62_sha_pd_1_20feb1828.jpg)

![Speech of the Earl of Shaftesbury on the second reading of the Factories Bill in the House of Lords, July 9th 1874 [MS 62 SHA/MIS/38]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/ms62_sha_mis_38.jpg?w=202)

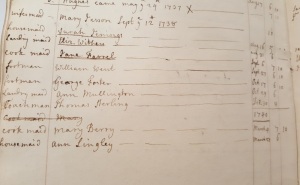

![Lord Shaftesbury’s diary, 1845-47 [MS 62 SHA/PD/4]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/the-official-ms62_sha_pd_4.jpg)

![The Ragged School Union Quarterly Record, January 1880 [MS 62 SHA/MIS/43]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/ms62_sha_mis_43.jpg?w=199)

![The works of Sir William Temple, bart. edited by Jonathan Swift [Rare Books quarto PR 3729.T2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/works-of-sir-william-temple-3.jpg?w=500)

![Prometheus, a Poem by Jonathan Swift [BR3/36]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/prometheus-crop-2.jpg?w=500)

![Swift's signature [MS 62 BR3/63]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/signature.jpg?w=500)

![Lord Palmerston as an elder statesman, West Front, Broadlands: an albumen print probably from the 1850s [MS 62 Broadlands Archives BR22(i)/17]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/palmerston-broadlands.jpg?w=235)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)