The next instalment in our A-Z series is ‘L’ for Livingstone, as this week we explore the papers of the Rev Isaac Livingstone (1885-1979), who was visiting Minister at Aldershot, 1907-8; Minister at Bradford, 1909-16; and Minister at Golders Green, 1916-53. He was secretary of the Union of Anglo-Jewish Preachers from 1925 onwards and a member of the council of Jews’ College, London, and of the Anglo-Jewish Association. Livingstone was Jewish representative on the National and London Council of Social Services and a member of the executive committee of the London Society of Jews and Christians.

The earliest sermons we have for Revd Livingstone date from his time at Aldershot and include his sermon delivered for the first day of Rosh Hashanah [the Jewish New Year] on Saturday 26th September, 5669 [1908 in the Gregorian calendar]. In this sermon Livingstone reflects upon the fleeting nature of time: “We are now on the threshold of a New Year. The year that has passed gone for ever. It cannot be recalled. Time indeed flies […] ‘We are strangers and sojourners: our days on earth are as a shadow'(1 Chronicles 29:15)”. He then quotes the psalmists’ words: “As for man, his days are as grass; as a flower of the field, so he flourisheth, for the wind passeth over it, and it is gone, and the place thereof shall know it no more” (Ps 103, 15, 16).

Livingstone notes that in the course of the preceding year, some in his audience have attended services with an ‘unmistakeable zeal and earnestness’ and he regrets that one amongst them is leaving town and will be absent in the following year. But he goes on to ask: “Will not some of those whose attendance has not been so regular make some endeavour to rectify their omission, so that the next Rosh Hashana […] has afforded an opportunity for the making of new resolutions which have been fulfilled.”

This year Rosh Hashanah will be celebrated from sundown on Sunday, 25 September 2022 and ends at nightfall on Tuesday, 27 September.

Whilst Minister at Bradford, Livingstone gave a sermon at the outset of the First World War:

“Since the last occasion on which this pulpit was occupied events have occurred which can only be described as terrible beyond words. To this momentous European crisis surely more than a word of reference should be made in our synagogues. Alas! that in this century of so-called civilisation the teachings of the pulpit – the teachings of religion, of morality, of love, of ethics are known to the dogs of war! Alas civilisations and creeds which preach the doctrine of peace and goodwill should in these days of peace conferences and peace societies, of international race congresses and arbitration leagues, find themselves compelled to settle their differences not by peaceable measures, but by killing and slaying, by bringing infinite suffering, ruin and desolation upon their fellowmen!”

Livingstone notes that although people will rejoice at each of their victories, they should not lose sight of the terrible suffering that each victory will bring. Despite his revulsion at the prospect of fighting, Livingstone (like many of his contemporaries) argued that the blame for the war was not England’s, for whom it was a defensive struggle fought for their independence and the defence of the liberty of smaller nations from ‘the tyranny of a great military despotism’. Later in his sermon Livingstone noted the shift in public opinion that had occurred in just a few weeks; whereas once some people were more ambivalent about Britain intervening in the conflict, since the invasion of Belgium almost everyone acknowledged the need to resist ‘a brutal policy which tramples upon small peoples, breaks treaties and forces the fearful business of war upon its neighbours’.

Livingstone asks his congregation what their duties as Jews should be amidst ‘what may prove to be the fiercest conflict in the history of the human race’. He notes that the children of Israel who have found a home in one country will be pitted against their co-religionists in another and he acknowledges that Britain has allied itself to other nations whose treatment of their own Jewish citizens has been un-exemplary. He urges the Jews of Britain to keep in mind the blessings of peace as well as the evils of war.

“And yet – in spite of all this, in spite of the anomalous position in which Jews as a race may find themselves, it is manifestly our duty to seek the welfare of the country of our own birth or adoption (as the case may be). It is obviously nothing more than a fulfilment of our rightful obligations to make what sacrifices we can on behalf of this country’s cause.”

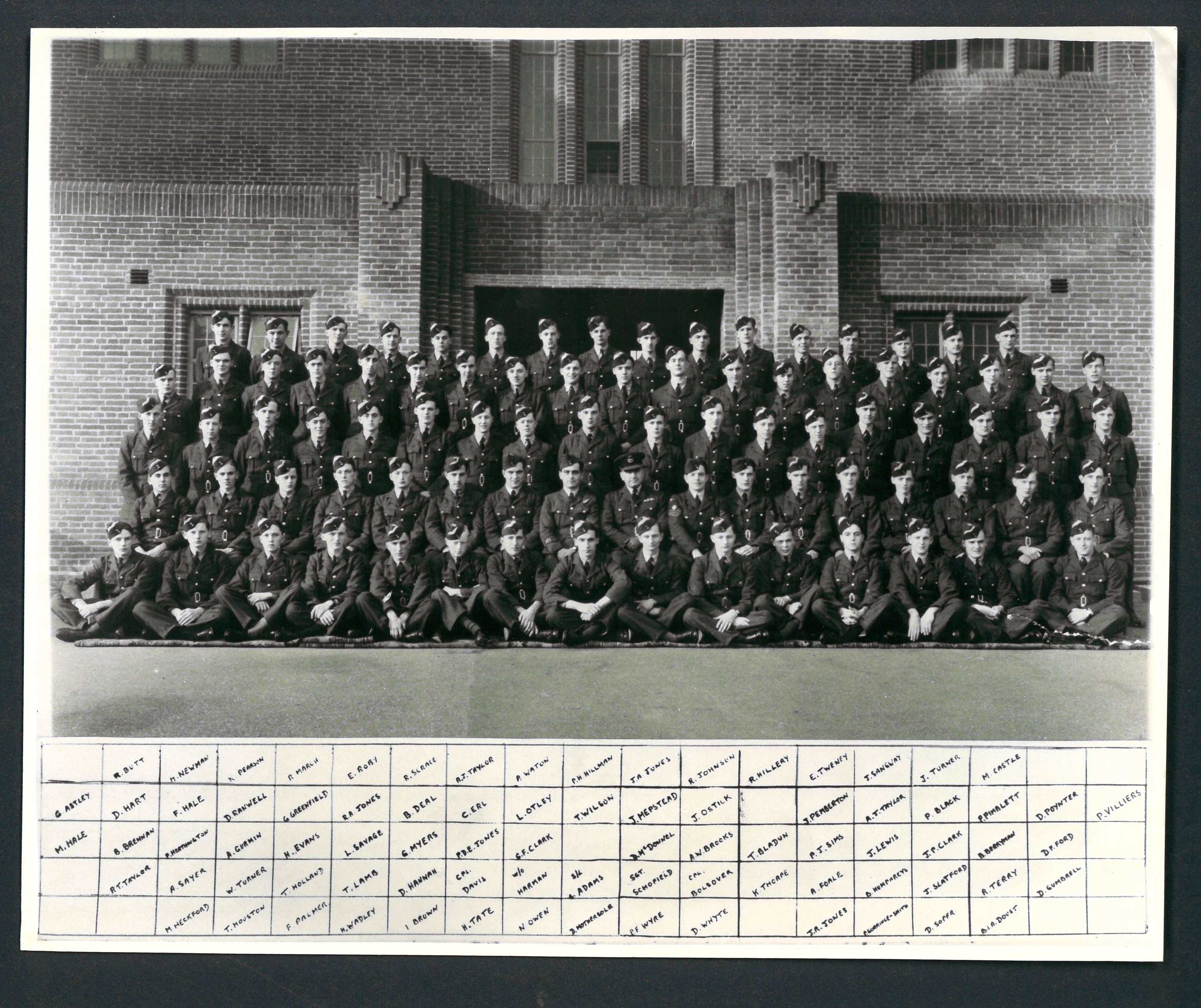

Livingstone tells his congregation that it is a religious obligation to be loyal to the British cause without at the same time diminishing their racial pride and self-respect: “It is therefore with a large measure of gratification that we view the voluntary enrolment of hundreds of co-religionists in London, Leeds, Manchester and elsewhere, willing to fight for this country’s interests.” Livingstone mentions his visit to the provincial regiment of the Jewish Lads Brigade, many of whom had responded to the call to arms. He encourages his congregation to give to the National Relief Fund, to avoid hoarding, and to volunteer in the manufacture of garments and bandages.

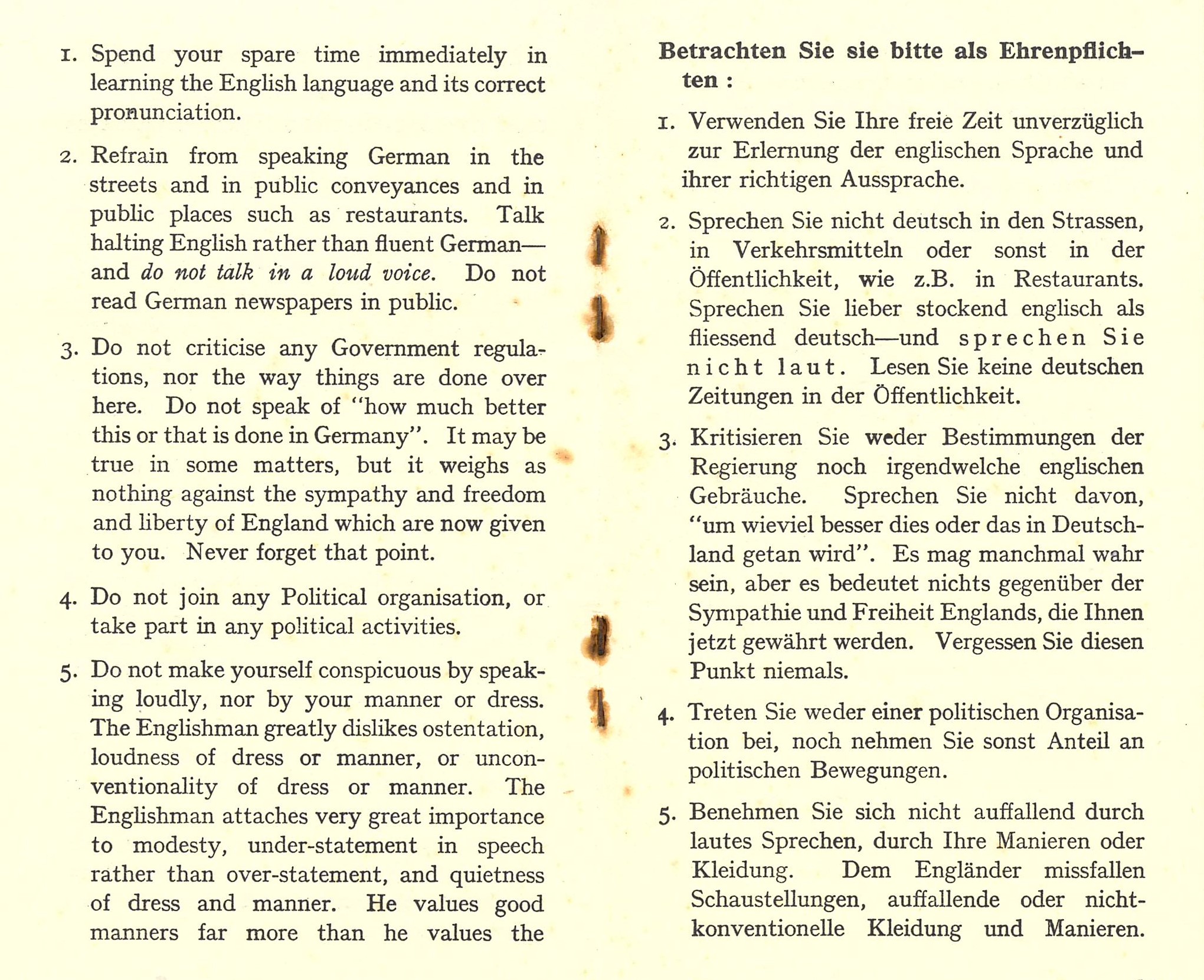

He admonishes those who attack German nationals in Britain:

“England’s conflict is not with the German people. This city [Bradford] in particular owes to them a great part of the mercantile structure of the West Riding. The progress of this city has been in great measure to German energy and skill […] our patriotic fervour ought not to degenerate into a chauvinistic hatred of the peoples of other countries […] The citizens of Bradford should treat with respect those [of German extraction] who as citizens have lived peacefully here – many of them for long years, and are not guilty of any acts of enmity.”

It was during the Great War that Livingstone’s ministry moved to Golders Green in London and he in fact gave a short address, as the representative of the Jewish community, at the formal unveiling by HRH Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll, of the Golders Green war memorial on 21st April 1923.

During the interwar period Livingstone became more involved with Christian-Jewish engagement and he became a member of the executive committee of the London Society of Jews and Christians. In a discussion at a meeting of the Union of Anglo-Jewish Preachers on 16th May, 1930 the Rev Livingstone noted that although all members were committed to the idea of brotherhood and fellowship amongst faiths, there was often reticence when any definite plans for engagement between the faiths was proposed. Livingstone contests the notion that Christian-Jewish engagement was the preserve of Reform Jews only, noting that cooperation with Christians was also part of Orthodox Jewish teaching. He notes the concern in the Jewish community that some Christians used interfaith engagement as a smokescreen for missionary activity. There is, he notes, too much ignorance about Jews and Judaism amongst Christians and this tended towards prejudice and ill feeling. For his part, Livingstone had been able to remove such ignorance and prejudice by engaging with non-Jews at Rotary clubs and elsewhere.

On Monday, 17th February, 1930 Livingstone spoke at a mass meeting of protest against religious persecution in Russia at the King Edward Hall, Finchley. A newspaper clipping reporting on the event tells us that the meeting was crowded and unanimously passed a resolution protesting against Soviet persecution of religion. The Rev. S.F.L. Bernays, Rector of Finchley, presided. The resolution was proposed by the Rev. Clement Parsons (North Finchley Catholic Church) and was seconded by Rev. Isaac Livingstone (Golders Green Synagogue): “Mr Livingstone was telling the audience of the large number of bishops and clergy who had been put to death in Russia without trial, when a woman at the back of the hall interrupted, and she was removed.”

Livingstone noted in his speech to the crowd that there are those who argue that the Russian government is entitled to do what it likes in its own country, and that outsiders should not interfere. He likens these people to the character in the Talmud who bores a hole into the bottom of his sailing boat and tells the other passengers aboard not to interfere in his business. What befalls our fellow man affects all of us.

In September 1939 Livingstone delivered a sermon to the Golders Green Synagogue, which included a special prayer, in which reference was made to the ‘spirit of perverseness’ which had come over the rulers of Germany, to their ‘idolatry of race and blood’ and the fact that they ‘violated the boundaries of nations’. He urged his listeners to obey in the letter and spirit all the instructions given for the public safety. Echoing his sentiments of 1914, he reminds his congregants that the new war was not a war against a people, but against a system and a regime of its leaders, and against the forces of evil which they had unleashed. Services at the synagogue would cease earlier than usual in order to comply with the new blackout regulations.

In the 1940s Livingstone continued to engage in Jewish-Christian dialogue, acting as a point of contact between the two communities in their discussions of the post-War world that they hoped for. In a letter dated 28th July 1941, Livingstone responds to the Rev Dr A.C. Craig of Hertfordshire on the ‘Social and Economic Reconstruction Statement’ circulated to Jewish ministers by the Commission of the Churches for International Friendship and Social Responsibility. Livingstone notes the reservations of one of his colleagues that, “…however spiritual and elevated their religious outlook may be, clergymen of any denomination are hardly the best builders of state systems.” This colleague also noted that the document seemed to envisage a “purely socialistic state in which private enterprise would not be allowed to exist” and that, whilst Jewish religious teaching is all in favour of opportunity and a radical improvement in social conditions, the statement goes far beyond this. Another of Livingstone’s colleagues noted that the plan of action called for in the document could only be realised through political action, and that there was a tendency in party-systems for one side to obstruct any proposal adopted by the other. Only a nation that is united behind a course of action can achieve social and economic reconstruction.

For his part, Livingstone makes the following, rather admirable and prescient, points:

“It may well be pointed out also that leaders of other civilised communities, besides Jews and Christians, have a strong sense of the need for social justice, human rights, and the fulfilment of responsibilities, and that what is wanted is a Brotherhood of Nations – an international and even inter-religious friendship and fellowship […] there should be no racial or religious tests, nor should colour or creed become a bar.”

Livingstone lived until 1979 and was, therefore, a witness to many noble attempts to live up to these hopes expressed during the dark days of the Second World War: the creation of the United Nations (the ‘Brotherhood of Nations’), and the growth of the human rights and social justice movements, as well as attempts to build a more tolerant and ecumenical post-war world.

When he wasn’t engaging directly with the political and social issues of the day, Livingstone’s sermons focused on Jewish life and practices. In a sermon given in 1953 Livingstone reflected on the meanings that can be drawn from traditional practices and rites:

“Furthermore, whilst emphasising the fact that there is a primary disciplinary value in the observance of Jewish laws and customs, which we regard as having a divine origin, it is surely helpful if the reasons for some of the observances are understood and appreciated.”

Such an approach to questions was taken by Livingstone in 1953 when, as part of an article on the theme of ‘Questions and Answers’, he called upon the reflections of other rabbis and scholars on the history and symbolism of the breaking of the glass at Jewish wedding ceremonies. He noted that the late Chief Rabbi Dr. J.H. Hertz said that ‘the glass is broken by the bridegroom as a reminder of the Destruction of Jerusalem’ and he added the following symbolisation of the rite – ‘even as one step shatters the glass, so will one act of unfaithfulness for ever destroy the happiness of the home.’

Livingstone also notes the story of Mar b. Rabina, who made a marriage feast for his son and when he observed that the Rabbis who were present were in an uproarious mood, so he seized a costly vase and broke it before them, to curb their spirits.

Livingstone was giving sermons from the pulpit at Golders Green until 1953 but thereafter he returned to give occasional sermons on special occasions, including his grandchildren’s bar mitzvahs. Amongst his papers are also the transcripts of speeches he gave to various bodies, including a speech given on 6th July 1961 to the Conference of Anglo-Jewish Preachers, as part of a remembrance service for the 50th anniversary of the death of the Chief Rabbi Dr Hermann Adler (1839-1911). Livingstone noted that, in 1961, he was one of only five surviving people of the 94 who were present at their first conference held in 1909, which also included Dr Adler.

Livingstone acknowledges Adler’s beautifully phrased and inspiringly delivered sermons and who set before himself the ideal of a Jewish pastor: “to mediate on the needs of his community; to be sensitive to all that might redound to Israel’s honour or besmirch its fair name”. He recollects that he first met Adler shortly after his own Bar-Mitzvah, when Harris Cohen, the Minister whom he had admired so much in his boyhood, sent him to go from Nottingham to London to be examined by Dr Adler, to see if he would be a suitable pupil for Aria College in Portsmouth. Livingstone recounts how he was inwardly shaking in awe and trembling in Adler’s presence, yet the man’s kind words of encouragement prompted him to take up the opportunities at Aria College and later at Jews’ College, London, in order to prepare him for his vocation in Jewish ministry.

Here in Southampton we hold many other collections featuring the sermons of Jewish ministers, including: the Papers of Rabbi Lerner of Hamburg; the sermons of Rabbi Dr Abraham Cohen of Birmingham; the sermons of Dr E.I. Spiers; as well as the papers of the Chief Rabbis Hermann Adler, Sir Israel Brodie, and J.H. Hertz.

![University College Southampton rowing crew, with Jefffery Turner [MS303 A1058/4/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/ms03_a1058_4_1_rowingcrew.jpg)

![CCJ “Model” Resolution document, 1942 [MS65 A755/2/1/14]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/04/ms65_a755_2_1_14r_0018.jpeg)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)