This blog will discuss the British government’s efforts in the release of Soviet Jewry, using the Papers of MP Greville Janner that are part of the MS254 A980 Papers of the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry.

The quote in the title is from Summary of paper on parliamentary action for release of Soviet Jewry- presented to European Parliamentary Conference of Soviet Jewry, Paris, 22 April 1977 by Greville Janner, QC. MP, Vice Chairman, British All-Party Parliamentary Committee for the Release of Soviet Jewry [MS254/A980/1/2/24].

The Soviet Jewry movement

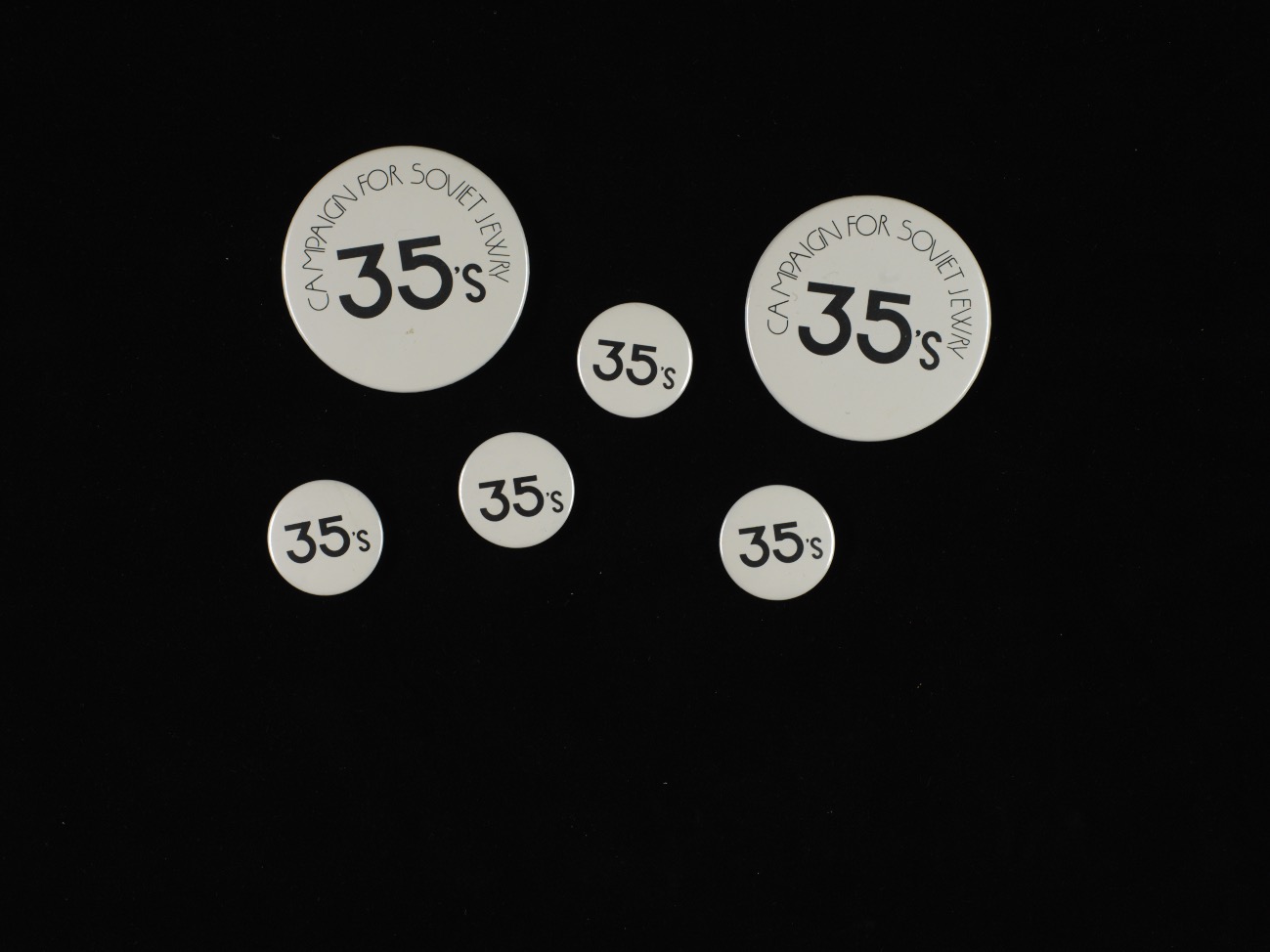

The Soviet Jewry movement emerged in response to the Soviet Union’s Jewish policy which was seen as a violation of basic human and civil rights, including freedom of immigration, freedom of religion, and the freedom to study one’s own language, history and culture. The Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry, known as the 35’s, was a pressure group established in London in 1971 with the aim of assisting Russian Jews wishing to leave the country but refused permission. These people were known as Refuseniks.

The establishment of the British All-Party Parliamentary Committee for the Release of Soviet Jewry

On 20 October 1971 the All Party Committee for the release of Soviet Jewry was formed. The committee looked something like this:

Chairman: Patrick Cormack

Vice-Chairman: Peter Archer

Honorary Secretary: Greville Janner

Honorary Treasurer: Hugh Dykes

Secretary to Committee: Mirs Veronica Hodges

Clerk to Committee: Jerry Lewis

Refusenik case study: Dr Yegveny Levich

In 1973 The All-Party Committee learnt with concern of the abduction of Dr Yegveny Levich on his 25th birthday. Dr Levich was the younger son of the Academician Benjamin Levich who was in the process of being dismissed from the Academy of Sciences for applying for him and his family to emigrate.

A number of Members of Parliament put down the following Motion on the Order Paper of the House of Commons:

“That this house deplores the abduction of Yegveny Levich, 26 year-old astrophysicist, son of Academician Benjamin Levich, of Moscow, who was taken by militia from his car while on his way to hospital and whose whereabouts are not now known; and calls on the Soviet authorities to free him forthwith and to permit all the Levich family to emigrate in accordance with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

The Parliamentary Committee sent the following telegram to Mr Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, who was in Germany at the time:

“The All-Party Committee for the Release of Soviet Jewry respectfully request immediate investigation into circumstances of arrest and subsequent press ganging of Dr Yegveny Levich into Soviet Army. He is seriously ill. The Welcome détente with USSR is jeopardised by the unprecedented mistreatment of a distinguished Jewish scientist.

Signed Patrick Cormack, Peter Archer, Hugh Dykes, Greville Janner”

The following notices of questions and motions were also given on Wednesday 27 October 1971:

“Motion Treatment of Jews in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

– Calls on Her Majesty’s Government to use its best endeavours and influence to secure and ensure respect of the human rights of the Jews who have been refused permission to emigrate to Israel and Russia’s refusal to permit Soviet Jews to freely practise their religion and to maintain their culture.

– To make special representations on behalf of those 39 Russian Jews, arrested in Moscow on 25th March 1970, for demonstrating on behalf of their relatives. Themselves arrested for seeking to emigrate to Israel.

– Calls upon Her Majesty’ Government to protest at the refusal of the Soviet authorities to permit foreign Press or observers to attend the current show trials of Soviet Jews.

– Calls for Her Majesty’s Government to bring to the attention of the Soviet Government the fact that more honourable Members have signed the honourable Members of Leicester North-West’s Motion calling attention to the plight of Russian Jewry, and that in the circumstances, the Soviet Government should now release its Jewish Prisoners of Conscience and in particular Silva Zlamason and Raiza Palatnik, who are in a desperate poor state of health as a result of their confinement in their strict regime labour camp. And the Soviet Government should now act in a civilised manner and in accordance with the international treaty and obligations and release those of its Jewish minority who wish to be repatriated with their families in Israel.”

Building support over the United Kingdom

Within the Janner papers are evidence of Members of Parliament attempting to build awareness of Refuseniks and how they were being treated in Russia. Janner spoke at a Bournemouth action committee meeting on 3 June 1972, which was organised by the Bournemouth branch of the Association of Jewish Ex-Servicemen and Women. The meeting was held to protest against the treatment of Soviet Jews. Janner told the meeting that Jews in professional jobs who had applied for visas to emigrate to Israel had lost their jobs and been forced to build roads or join the army or be imprisoned. Committees to help Soviet Jews were springing up all over Britain he added. The women present at the meeting formed the 35 Group after hearing a talk by Mrs Janner. They planned to intercede for imprisoned Jewesses and stand in vigil outside the Soviet Embassy. Janner later received a letter from a Mr K. Kirsch of Bournemouth to inform him that a committee had been established, namely the Bournemouth Non-Denomination Action Committee for the Release of Soviet Jewry. The Bournemouth group planned peaceful demonstrations, letters to people in prison, phone calls to those being harassed, and a Bournemouth 35 group was also formed.

Meetings were also addressed in Glasgow, Leeds, Manchester, Birmingham, Cardiff and Bristol. Members of All Parliamentary Committee for the Release of Soviet Jewry constantly harassed members of the Soviet Embassy and raised questions in Parliament.

Janner described the great work being done by the “35 group” and how these ladies devoted a great deal of time bringing the plight of Soviet Jews to public notice and by telephoning Soviet Jews in Russia to let them know they are not forgotten.

Use of political connections in the United Kingdom and across the world

Key documents within the papers of Greville Janner reflect efforts made to use political connections to galvanise support for the Refuseniks and to use political influence to make a difference to the way they were being treated. Such documents include correspondence with Winston Churchill’s grandson, Winston Churchill and former British Prime Minister Harold Wilson. In September 1971 Janner thanked Winston Churchill for joining Patrick and himself to form the new All-Party Committee for the Release of Soviet Jewry. He also requested him to be Chairman and revealed his wish to launch the operation on 20 October 1971.

In February 1972 Janner requested Harold Wilson to make a ‘behind the scenes’ approach to assist Vladimir Slepak in leaving Moscow with his wife and 12 year old son. Janner later sent Wilson a list of persons in Moscow who have children in England, of which Wilson promised to take with him on his trip to Moscow and attempt to try to get the fathers released.

When in Washington for the World Jewish Congress meeting, Greville Janner had a series of meetings with the United States Senators and Congressmen to discuss how Parliamentarians in the two countries could coordinate their efforts in the campaign. Among the results of this initiative was a joint approach by Senator Abe Ribicoff and Mr Janner to the Soviet, United States and British Foreign Ministers and Belgrade delegates on behalf of the Slepak family (of whom Janner has campaigned for seven years for their release); plans for future cooperation with Senator Jack Javits and arrangements for the exchange of information in future.

A letter is also included to the Minister of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, Joseph Godber, ESQ. MP, on 28 July 1972 requesting to look into the matter of Academician Benjamin Levich who had been offered and had accepted a fellowship at the University College, Oxford and yet had been refused permission to leave Russia. Janner requests Godber to take up his case with the Russian authorities.

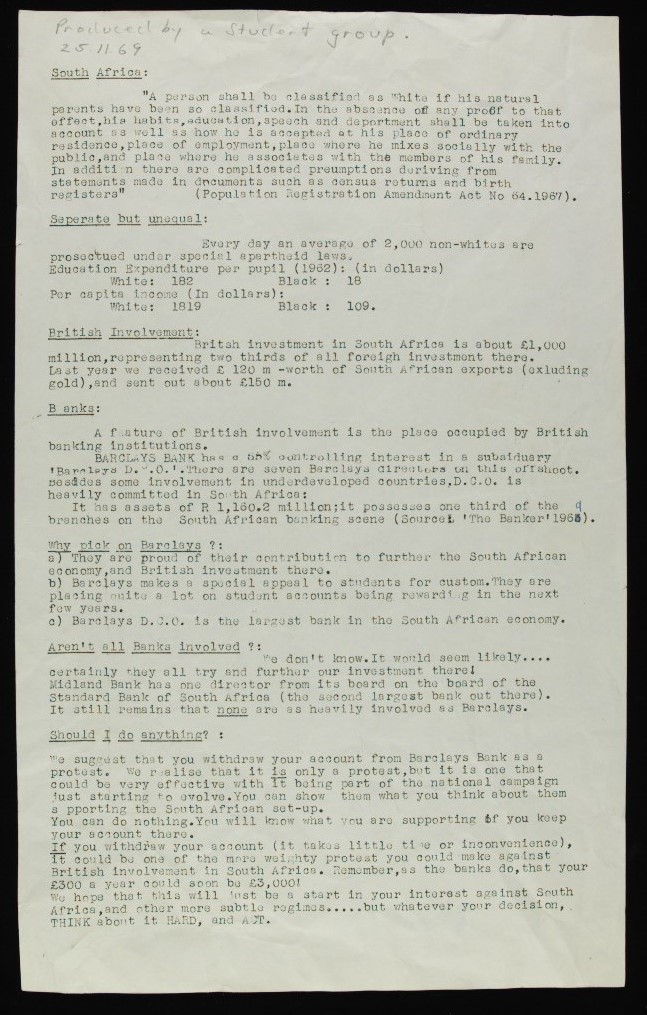

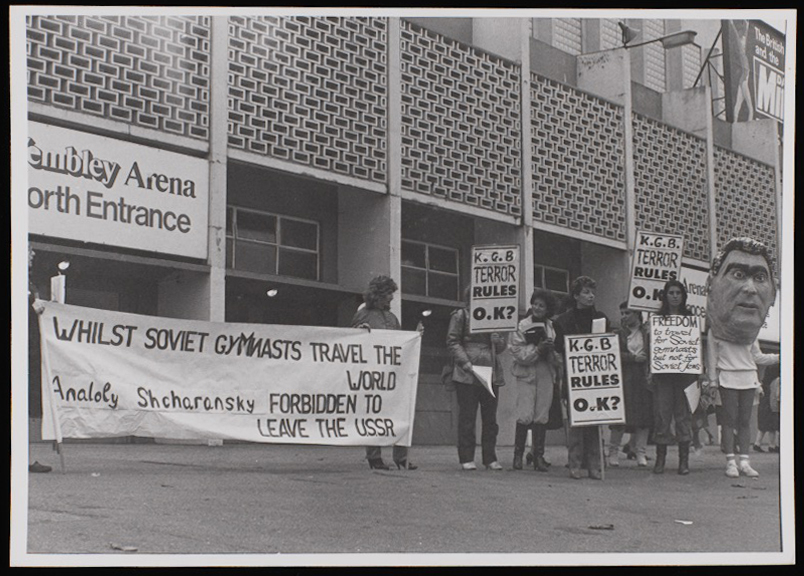

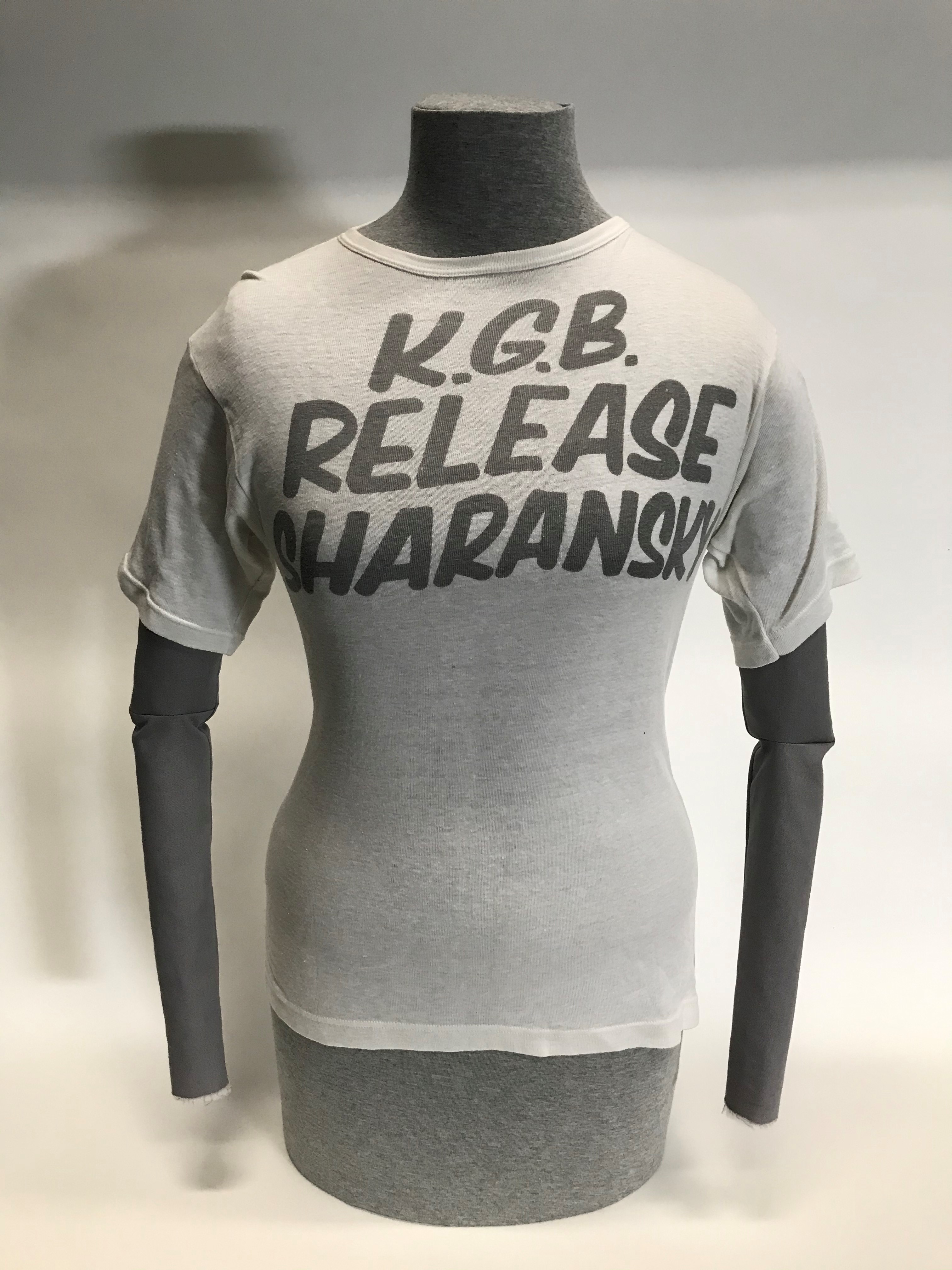

Methods used to raise public awareness of the treatment of Soviet Jewry

By reading the minutes of meetings of the All-Party Committee for the Release of Soviet Jewry, you can find out what methods were used to help the Refuseniks. Methods included visits to Russia to make contact with Jewish activists, visits to Israel, writing letters to the major newspapers such as The Times on the cause, raising awareness of the problems of Soviet Jewry at events during Soviet Delegation visits, and even attempting to disallow Soviet politicians from entering the country until Refuseniks were permitted to leave the Soviet Union.

On 2 July 1974 an exhibition was held at St Martin’s in the Fields Church for two weeks designed to highlight the plight of Jews in the Soviet Union which was sponsored by the Parliamentary All-Party Committee and opened by the Archbishop of Canterbury. This included a number of photographs of the Moscow synagogue by Mel Di Giacomo.

The All-Party Committee even received guidance from the Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry on writing letters to the Refusenik to ensure they wrote their letters in a way that would ensure they went to the addressee and would not be destroyed by Soviet authorities.

Below is a summary of parliamentary action for release of Soviet Jewry presented to the European Parliamentary Conference of Soviet Jewry, Paris, 22 April 1977 by Greville Janner:

“Methods of pressure, which have proved helpful:

(1) Top level, behind the scenes – requests by Presidents, Prime Ministers, governments or trade unions for (a) changes in general policy and/or (b) release of individuals. Pressures usually brought at request of Parliamentarians and/or constituents- and at best reflect manifest feeling in country concerned.

(2) Delegations visiting Soviet Union- parliamentary, trade union and trade- emphasising the difficulties of “doing business” (political or commercial) with Soviet Union while e.g. Anatoli Sharansky in prison or e.g. Slepak family harassed.

(3) Scientific Delegations- or individual visits – emphasising persecution of Academician Levich, Professors Lerner, Fein etc and banning of Scientific Symposium.

(4) Individual visits- by e.g. Parliamentarians, churchmen or tourists, with access to influential Russians.

(5) Parliamentary protests – which may range from legislative attempts to tie trade to human rights issues (e.g. controversial attempt- USA); through motions, resolutions speeches, debates questions to Ministers, letters to Governments (released to press) etc. Individuals in immediate danger should be named – knowledge that harm to them will cause international outcry is their best (and frequently only) protection.

(6) Pressure through media – Parliamentarians have easier access to press, T.V. and radio than almost anyone else. Every opportunity should be taken to introduce campaign.

(7) Public demonstrations- Parliamentarians (well known figures) may spearhead campaigns by others e.g. by speaking at or chairing meetings; leading marches or protests; accompanying delegations to Soviet Ambassador or visitors.

(8) Direct approaches to Soviet Authorities

(a) At home- through private contacts with Soviet Ambassador and/or his staff; at diplomatic parties; through parliamentary Soviet friendship groups

(b) Through official delegation to Soviet Ambassador etc Parliamentary or mixed or through an attempt to arrange such delegations

(c) Within Soviet Union – cables, letters , telephone calls etc- to both top and local officials, No reply likely but reactions sometimes dramatic.

(7) Demonstrations with Parliament – sometimes possible to dramatize plight of Soviet Jews e.g., “Prisoners” luncheon – with press; Slepak prayer book; exhibitions.

(8) Personal contact with Refusniks

(1) By telephone. If lines cut off parliamentary/governmental protests should follow.

(2) Letters- sometimes arrive but intercepted by censors, nevertheless inform authorities of parliamentary concern.

(3) Visits-all parliamentarians who visit Soviet Union should be asked to see “Refusniks” either at their homes or visitor’s Hotel.

(9) Co-operative efforts- inter-parliamentary – coordinated efforts on behalf of indivudals (e.g. Dr Stern) and or on specific issues (e.g. education tax) have proved valuable but are too few. Could coordination through Parliamentary Soviet groups and/or activists not be extended? European parliamentary efforts (Per Ahlmark) have been notable but individual groups have had too little contact.

(10) Public relations – Parliamentarians best to explain the cause. And to answer counter-attacks to explain need for separation between Jewish movement to leave Soviet Union and dissident efforts to change regime within and to answer Soviet propaganda.”

Other useful documents for studying the efforts of the British government in the release of Soviet Jewry include notes on chairman’s reports from AGMs and correspondence regarding the threat posed to Israel’s status in the United Nations.

Chairman’s Report [MS254/A980/1/2/30]

Stay tuned for our next blog post, which will focus on Charlie Knight and his research using MS314 Papers of Theodore Hirschberg, 1939-41.

![Raiza Palatnik [MS254/A980/2/16]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/edited_ms254_a980_2_16_2_raisa_palatnik.jpg?w=710)

![Michael Sherborne [MS434 A4249 7/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms-434_a4249_7_2-portrait-photo-of-michael-sherbourne.jpg?w=189)

![Young Michael Sherbourne, 1939 [MS434 A4249 7/3]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_7_3-young-michael-sherbourne.jpg)

![Michael Sherbourne and his wife Muriel in USA, 1989 [MS434 A4249 7/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_7_2-michael-sherbourne-and-his-wife-muriel.jpg)

![Michael Sherbourne on the telephone with his recording equipment, c.1980s-1990s [MS434 A4249 7/4]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms-434_a4249_7_4-michael-sherbourne-on-telephone.jpg)

![Women’s Campaign for Soviet Jewry calendar, 1989 [MS 434 A4249 5/6]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms-434_a4249_5_6-womens-campaign-for-soviet-jewry-calendar-1989.jpg)

![Poster for talk given by Michael Sherbourne on ‘Russian Jewry Past, Present, and Future’, 2004 [MS 434 A 4249 1/3 Folder 8]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_1_3-folder-8-michael-sherbourne-talk-poster.jpg)

![Front cover of We are from Russia by Paulina Kleiner translated from Russian by Michael Sherbourne , MS434 A 4249 2/1/1 Folder 1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_2_1_1_folder1-we-are-from-russia-front-cover.jpg)

![Michael Sherbourne on protest march in San Francisco near the Soviet Consulate, [MS434 A4249 7/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/ms434_a4249_7_2-michael-sherbourne-marching-in-protest.jpg)

As part of the Explore Your Archive campaign the Special Collections team will be hosting two events. On Wednesday 22 November, there will be a drop-in session highlighting an array of material from the manuscript and printed collections relating to protests, rebellion and revolution.

As part of the Explore Your Archive campaign the Special Collections team will be hosting two events. On Wednesday 22 November, there will be a drop-in session highlighting an array of material from the manuscript and printed collections relating to protests, rebellion and revolution.

![Extract from grant for a subscription for a trading voyage [MS62 BR4/1/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/ms62_br4_1_1_crop.jpg?w=500)

![Jewish children, probably from Czechoslovakia, c. 1946 [MS 241/4/2/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/jewishchildrenczech.jpg?w=300)

![20,000 students gathered in a rally of solidarity with the Jews of the Soviet Union, 2 December 1969 [MS 237/3/159 f1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/studentrally.jpg?w=300)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)