As today is National Handwriting Day in the United States, we have decided to provide a short introduction to palaeography – an essential skill for any budding historian or archivist!

What do we mean by palaeography?

Palaeography literally means ‘old writing’ from the Greek words ‘paleos’ = old, and ‘grapho’ = write. The term is now generally used to describe reading old handwriting.

How we read

The human mind deos not raed ervery lteter by itself, but the word as a wlohe. The order of the ltteers in the word can be in a toatl mses but you can still raed it wouthit any porbelm.

We expect to recognise words and letter shapes but this doesn’t happen with unfamiliar handwriting. Instead we need to look at the individual letters separately and break the words into their most basic form.

Some tips for reading documents

While you’re reading:

- Try to identify individual letters:

- Compare them with similar-looking letters on words you have already deciphered.

- Look at the adjacent letters, considering which letters are likely to sit together. For example –act would be more likely than –acx.

- You don’t have to start at the beginning. When faced with a difficult or unfamiliar style, look through the document for a passage you can read (more) confidently.

Why not have a go at reading the Duke of Wellington’s handwriting:

![Letter from Arthur Wellesley, later first Duke of Wellington, to Henry Bathurst, third Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies [MS61 Wellington Papers 1/373]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/wellington-scum-letter2.jpg?w=500&h=312)

Letter from Arthur Wellesley, later first Duke of Wellington, to Henry Bathurst, third Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies [MS61 Wellington Papers 1/373]

Abbreviations

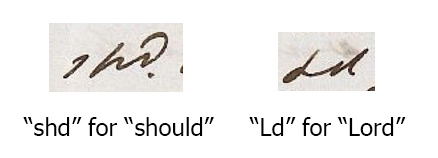

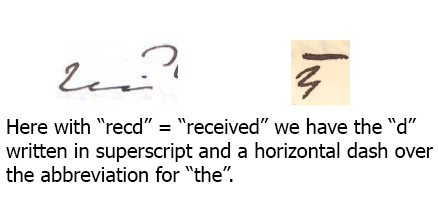

The most common form of abbreviation is by contracting a word by missing out letters from the middle:

Sometimes a horizontal dash, or other mark, would be made over or under the missing letters to highlight the omission.

Spelling

Spelling was not standardised until the eighteenth century. Spelling of names and places can vary greatly, sometimes in the same document. Often phonetic spellings were used. However, this becomes less of an issue over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Numbers

Numbers changed shape for example 8, often when used in dates, could be an old-fashioned form where the top loop was to the right of the lower loop, making it tilt over.

Letter forms

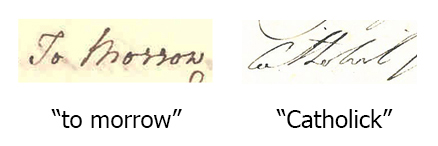

When a word will not fit onto a line, it will be split onto two lines – sometimes without hyphenating the two bits of the word, or using = on the second line.

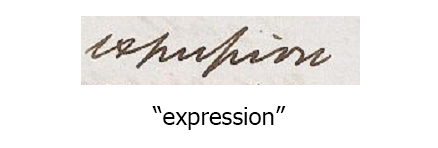

The long s, resembling an f, is usually the first used in a double s word, such as “expression” here. To avoid getting the long s and f mixed up, the f will have a cross stroke, even if it’s hardly noticeable.

With more formal language, there might also be an unusual use of capital letters, often emphasizing important words.

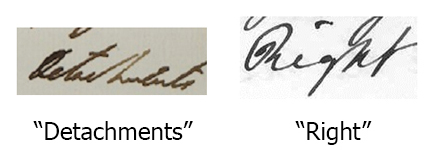

Changed letter shapes: for instance the letter h was sometimes written with the stick above the line of text and the letter p (particularly on the end of words), could often look like an f.

Handwriting

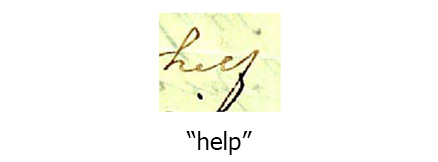

Styles of handwriting have been influenced by the challenges of writing with pen and ink. The way the shape of the letters flow results from the shape of the quill or nib. The downstrokes were usually heavy, with the upstrokes lighter as the pen pushed against the paper, rather than scratched into it.

The example below is a document drafted in the hand of Prime Minister, Henry John Temple, third Viscount Palmerston:

![Heads of proposed arrangements for the future government of India, drafted in the hand of Prime Minister, Henry John Temple, third Viscount Palmerston [MS 62 Palmerston Papers CAB88B]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/palmerston-proposal-india.jpg?w=500&h=370)

Heads of proposed arrangements for the future government of India, drafted in the hand of Prime Minister, Henry John Temple, third Viscount Palmerston [MS 62 Palmerston Papers CAB88B]

So, palaeography is not a theory. It is a skill which will improve with practice. It is often just a case of “getting your eye in” and becoming familiar with the handwriting.

Interested in exercising your palaeography skills a little more? Then be sure to check out The National Archives’ online palaeography tutorial at:

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/palaeography/

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)