This week we hand the reins over to Roger Ottewill for a blog on John Bullar, Southampton clergyman and historian. Much of Bullar’s library can now be found in the Hartley Library’s Special Collections, presented by his sons “as a lasting memorial of the interest which their father took in the Institution and of the earnest desire which he ever felt to promote by all means in his power the mental and spiritual improvement of his fellow-men.”

Among Southampton Historians John Bullar stands out as having received the ultimate accolade of an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography [ODNB]. Written by Barbara Spender this provides a succinct assessment of his life and works (see Figure 1).

She makes the point that his Christian ‘faith underpinned his diverse writings which ranged from a series of locally based historical and geographical tourist guides, to a collection of edifying poetry with which he sought to counter the anti-religious tide of popular culture epitomized by the poetry of Lord Byron.’ His very close links with Southampton, where he lived for the whole of his life, are also highlighted. In this vein, she concludes with words taken from his obituary in the Southampton Times: ‘The life of Mr Bullar is in fact the life of Southampton during the past fifty years.’ (ODNB, p.600). In another obituary, taken from the Salisbury and Winchester Journal, he is described as an ‘exemplary Christian, and a learned, eloquent and able man’ (21 May 1864, p.8).

Bullar is also memoralised by having one of the streets in Bitterne Park named after him (see Figure 2). As A.G.K.Leonard explains in Stories of Southampton Streets this was to serve ‘as a memorial to a man who was involved in many liberal and humane causes, working ceaselessly to promote the spiritual and material progress of his town’ (p.83).

The principal aims of this blog are to provide some biographical information and summaries of his key historical works, which are held in Special Collections. It is hoped that this will inspire others to consider further Bullar’s contribution to the development of Southampton’s cultural life and the influences which shaped his personality and, what today would be called, his ‘world view’.

Biographical Overview

Born on 27 January 1778, John Bullar’s parents were John Bullar senior (1744-1836) ‘a peruke maker and hairdresser of Southampton High Street’ and Penelope, nee Rowsell (1755-1799). He was the eldest of eleven children, although only three survived into adulthood. Educated at King Edward VI Grammar School he was clearly an industrious scholar since he subsequently became a schoolmaster, teaching in ‘his schools in Bugle Street, Moira Place and Prospect Place’ (ODNB, p.599). As pointed out by Barbara Spender, many of the civic leaders of Southampton received their initial education from Bullar.

John and Penelope had six children, four sons and two daughters. Three of their sons became doctors, with two of them, Joseph and William, being closely involved with the Royal South Hants Infirmary. One of their daughters, Ann wrote a number of well received educational works mainly for the young.

A powerful influence throughout Bullar’s life was his religious affiliations and sensibilities. Although baptised an Anglican, his marriage in 1806 to Susannah Sarah Whatman Lobb brought him within the orbit of the prestigious Above Bar Independent (later Congregational) Chapel, where her parents were leading members (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Above Bar Congregational Church interior and exterior (Source: Avenue St Andrew’s URC Archive)

Subsequently, a member of the Chapel for the remainder of his life, Bullar served as a deacon for 43 years. Interestingly, however, his funeral service in 1864 was conducted by the Bishop of Rochester, with whom he had a close friendship. This led to the Birmingham Daily Post headlining its report, “A Dissenter Buried by a Bishop” (23 May 1864, p.3).

Historical Works

From the perspective of Southampton’s history, undoubtedly his most significant work was Historical Particulars relating to Southampton, published in 1820. However, in the foreword (or ‘advertisement’ as it is headed), Bullar makes the following ‘disclaimer’:

The following particulars which are presented to the public in the following pages, were collected at intervals, in the course of reading, many years ago. They were seen by the late ARTHUR HAMMOND, Esq. who urged the compiler of them to undertake a history of his native place; offering to use his influence with the Corporation, to obtain access to the sources of information in their archives. Want of leisure prevented him from availing himself of so liberal and important an offer; and the same cause is likely to continue to operate. His friend, Mr. THOMAS BAKER, however, unwilling that the few collections he had made, should be altogether lost, undertook to publish them. In this imperfect form, they bespeak the candour of the public: to which they are committed, with a hope that the publication of them may stimulate some able person to take up a subject, which might be made, it is probable, both instructive and entertaining.

Shortcomings notwithstanding, Bullar’s hope was certainly realised with this work serving to inspire later historians who used it as their starting point.

To provide a flavour of the accessible nature of the work, below are a couple of extracts. With respect to his beloved Above Bar Independent Church, he wrote that following the ejection of the Revd Nathanial Robinson from All Saints Church in 1662 and his remaining in Southampton:

At first on account of the persecution which then raged, they were under the necessity of assembling when and where they could. Afterwards, some houses were converted into a place of worship, in which, as the times would allow, they attended their Sabbaths and their monthly sacraments. They held also monthly fasts, at which they constantly made collections for the poor; thus assisting not only the needy of their own society, but even occasionally sending help to the persecuted Protestants of France … In 1727, a neat place of worship was erected, which was enlarged in 1802, and taken down and substituted with the present building in 1820 (pp.95-6).

On a different subject, namely ‘boundaries’, he had this to say:

Southampton being a county of itself, a procession round the boundaries is occasionally made (till lately the ceremony was annual) by the sheriff, court-leet, and as many of the housekeepers who chose to attend: all of them are summoned and a fine of one penny is demanded on their refusal. – This cavalcade, which has obtained the popular name of cut-thorn, from the season when it takes place, sets out on the morning of the second Tuesday after Easter Tuesday, from the Bar-Gate, and after having made a complete compass of the county, re-enters the town at the bridewell gate. At the various boundary marks on the road, several ludicrous ceremonies are performed by those who have never before attended the procession. In the course of their circuit, refreshment is provided for them; in a tent erected on the common; and the day frequently terminates with greater credit to the hospitality of the Sheriff, than to the moderation of his guests (pp.107-8).

As can be seen, in places Bullar sought to inject an element of humour and/or sarcasm into his narrative.

Another work, Bullar’s guide to Netley Abbey, was sufficiently popular to run to at least nine editions, the last being published in July 1844. Described as a ‘companion’, this provided visitors with not only details of the buildings but also the life of those for whom the Abbey was their home.

The preface to the fourth edition of a Tour Round Southampton (1810) provides a fair indication of its geographical and historical scope with it:

Comprehending various particulars, ancient & modern of the New Forest, Lymington, Christchurch, Ringwood, Romsey, Winchester, Bishop’s Waltham, Titchfield, Gosport, Portsmouth &c, with the notices of the Villages, Gentlemen’s seats, Curiosities, Antiquities &c occurring in the different roads described , and various Biographical Sketches.

Clearly this was intended to encourage those visiting Southampton to enjoy other delights within the county and not restrict themselves to the town and its immediate environs. Thus, Bullar could be said to serve as a historiographical muse for not only future Southampton historians but also those whose interests lay elsewhere within Hampshire.

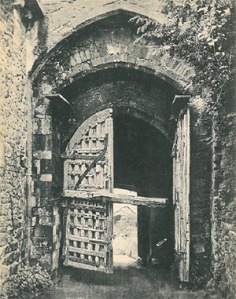

Lastly, reference should be made to Bullar’s guide to the Isle of Wight which covered all parts of the island and again ran to nine editions. In the later editions, the text is supplemented with an increasing number of engravings which serve to add interest and illuminate his descriptions of many of the principal buildings and vistas (see Figures 4 a-d for some examples).

“Entrance to Carisbrooke Castle” from the Historical and Picturesque Guide to the Isle of Wight by John Bullar, 9th ed. (1840) [Rare Books Cope 98.035 1840]

“Arched Rock” in Freshwater bay from the Historical and Picturesque Guide to the Isle of Wight by John Bullar, 9th ed. (1840) [Rare Books Cope 98.035 1840]

“Appuldurcombe” from the Historical and Picturesque Guide to the Isle of Wight by John Bullar, 9th ed. (1840) [Rare Books Cope 98.035 1840]

“Niton” from the Historical and Picturesque Guide to the Isle of Wight by John Bullar, 9th ed. (1840) [Rare Books Cope 98.035 1840]

His coverage, however, is not restricted to the grand houses, but also includes references to Parkhurst Prison and the House of Industry (i.e. workhouse).

Other Publications

In view of his strong Christian faith it is unsurprising that among his published works are many of an overtly religious character. These include: The impartial testimony of a layman, against the errors of the present times, and in favour of the Holy Scriptures: being the substance of a speech delivered at the fifth anniversary of the Southampton Bible Society. Nov 10, 1819 and Harvest home and lord of all harvests: a lay lecture, published in 1854. A few years earlier, in 1846, he had published a collection of his lay lectures, under the title Lay Lectures on Christian Faith and Practice. This was described is one of his obituaries as being ‘marked with good sense, clear reasoning, much research and considerable eloquence and stamped the author as a man of learning and talent’ (Salisbury and Winchester Journal 21 May 1864, p.8). Many of his lectures were delivered at the Mechanic’s Institution and the Literary and Philosophical Institution. As indicated earlier, alongside history and religion, another of his interests was poetry. This was evidenced by the publication in 1822 of Selections from the British poets: … with select criticisms … and short biographical notices.

Conclusion

Without doubt, Bullar was a leading figure within Southampton’s intellectual elite during the first half of the nineteenth century. Judging by the tributes paid to him both during his life and following his death it would be difficult to overstate his reputation. A true son of Southampton he was strongly motivated to improve the welfare and sensibilities of his fellow townsmen. His final resting place is in the churchyard of St Nicholas’ Church, North Stoneham (see Figure 5).

![Redhill, August 1876 by Sissy Waley [MS 363 A3006/3/5/4 page 37 1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/ms363_3_5_4_p37_1aredhill_1876.jpg)

![Watercolour of view in the garden at Northcourt, 18-- [MS 80 A276/5]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/ms80_a276_17_5_cropped.jpg)

![Watercolour of garden just made at Northcourt, 1843 [MS 80 A276/17/3]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/ms80_a276_17_3_cropped.jpg)

![Pride of India, Cape Province, 1932, by Charlotte Chamberlain [MS 100/1/3]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/ms100_1_3pride-of_india_1.jpg)

![Red gum, Cape Province, 1932 [MS100/1/3]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/ms100_1_3croppedred_gum.jpg)

![From Beddgelert [MS363 A3006/3/5/4 page 37 number 2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/ms363_3_5_4_p37_2frombeddgelert.jpg)

![View from Cricceth Castle, 1878, by Julia Cohen [MS 363 A3006/3/5/4 page 45 number 2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/ms363_3_5_4_p45_croppedfromcricceth.jpg)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)