With this year marking the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen and Halloween being almost upon us, we explore the gothic ruins of Netley Abbey – the inspiration for many a literary endeavour…

Lying on the eastern bank of Southampton Water, Netley Abbey is one of the best surviving Cistercian abbeys in England. The abbey was founded in 1238 by Peter des Roches, the Bishop of Winchester, shortly before his death. The following year a colony of monks arrived from nearby Beaulieu Abbey (founded by King John in 1203). Netley was dedicated in 1246 and, following its completion, was home to about 15 monks and 30 lay brothers, officials, and servants. Henry III became a patron in 1251, bringing great wealth to the abbey.

Netley Abbey Overgrown

The dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII brought monastic life at Netley to an end. Following its seizure in 1536 the buildings were granted to Sir William Paulet, a loyal Tudor politician, who converted them into a mansion. The abbey was used as a country house until the early 18th century, after which it was abandoned. At this time much of the brickwork added by Paulet was removed to be used for building materials. The site then fell into neglect, becoming overgrown with trees and ivy.

In time, the site came to be celebrated as a romantic ruin, eventually becoming a tourist attraction and providing inspiration to writers and artists of the Romantic Movement, including John Constable, Thomas Gray, and Horace Walpole. The latter wrote that “they are not the ruins of Netley, but of Paradise”. It is also believed that Jane Austen drew inspiration from the abbey for her Gothic parody Northanger Abbey.

Visitors at Netley Abbey

Among the numerous other visitors was Mary, Viscountess Palmerston, who recorded her visit in a letter to her husband, the second Viscount, on 6 August 1788:

On Monday we set off from Southampton at ten in an open boat as there was not wind enough to allow of our making use of the cutter. Our party, the Hatsells, Sloane, Stephen, Maria, Captain Southerby, Mr Ballaird and a Mr and Mrs Barton great friends of the D’Oyleys, and in truth in that consists all their merit, for I have not often seen more disagreeable people. We had a most delightful row to Governor Hornby. I think you have been there and I dare say admire the situation which is in my opinion in point of view superior to anything in this country. We went on board the yatch which lies at anchor in the Hamble River which is certainly a most complete vessel. We then row’d up to Netley where we had a most elegant dinner, Sloane having sent his cook to prepare our repast, and in the cool of the evening we repair’d to the Abby which considering every circumstance of the trees, the emannance of the ivy, the beautiful state and the situation of the ruins please me more than any I ever saw. We drank tea in the abby and came home by land. I return’d to Broadlands that night.

[MS 62 Broadlands Archives BR 11/13/1]

The Cope collection contains a range of material relating to Netley Abbey, including early guidebooks, poems, a novel, and even an opera. Evidence of its popularity can also be found in the wealth of visual material among the collection.

Two of earliest items are poems. The Ruins of Netley Abby: a Poem, in Blank Verse: to which is Prefixed A Short Account of that Monastery, from its First Foundation, Collected from the Best Authority was printed in 1765. This anonymous history and poem was published during the early years of Netley’s fame and creates a vivid image of a haunted Gothic ruin:

Though claps of thunder rock and tottering pile,

And the swift lightning’s oft repeated flash

Glance through the window with its fading fire—

Or if some meteor in the great expanse,

With streaming flame o’erhand the shaggy top,

Casting a glare amid the foliage wild,

That spreads romantic o’er the abby walls—

Though from some dark recess with ghastly stare,

An airy troop of pale cold shiv’ring ghosts

Should lightly skim along the lonesome void,

By the blue vaporing lamp here let him sit,

Or by the twinkling glow-worm’s yellow light,

Behold the hour-glass ebb, and grain by brain

The trickling sand descend; whilst o’er his head

Along the broken structure hoar and rough

The moping scriech-owl, fatal bird of night,

Claps ominous her wings, foreboding death.

[The ruins of Netley Abby : a poem, in blank verse (Rare Books Cope NET 26)]

Netley Abbey, an Elegy by George Keate (1729–97) was first published in 1764, with a second expanded edition appearing in 1769. Keate was a poet, naturalist, antiquary, and artist, best known for his poem The Alps, a Poem which was praised for its “truth of description and vigour of imagination.” In his Netley poem he sets a melancholy mood as he provides topographic descriptions of the abbey alongside moral reflections:

I hail at last these shades, this well-known wood,

That skirts with verdant slope the barren strand,

Where Netley’s ruins, bordering on the flood,

Forlorn in melancholy greatness stand.

How changed, alas! From the revered abode,

Graced by proud majesty in ancient days,

When monks recluse these sacred pavements trod,

And taught the unlettered world its maker’s praise!

Now sunk, deserted, and with weeds o’ergrown,

Yon prostrate walls their harder fate bewail;

Low on the ground their topmost spires are thrown,

Once friendly marks to guide the wandering sail.

[…]

Oh! Trust not, then, the force of radiant eyes,

Those short-lived glories of your sportive band;

Pleased with its stars, through laughing morn arise,

A steadier beam meridian skies demand!

Reflect, ere, victor of each lovely frame,

Time bids the external fleeting grace fade,

’Tis Reason’s base supports the noblest claim,

’Tis sense preserves the conquests Beauty made.

[Netley Abbey, an Elegy (Rare Books Cope NET 26)]

The second edition of the poem increased the number of stanzas from 26 to 50 and can be found reprinted with John Bullar’s Visit to Netley Abbey (discussed further below).

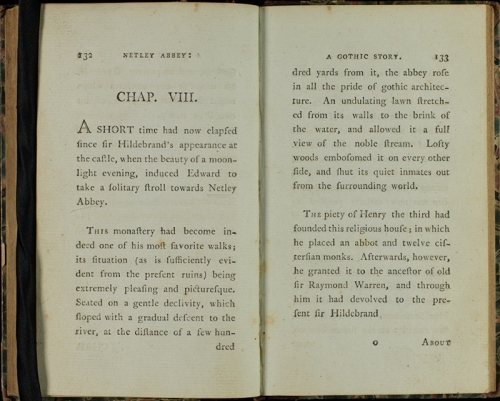

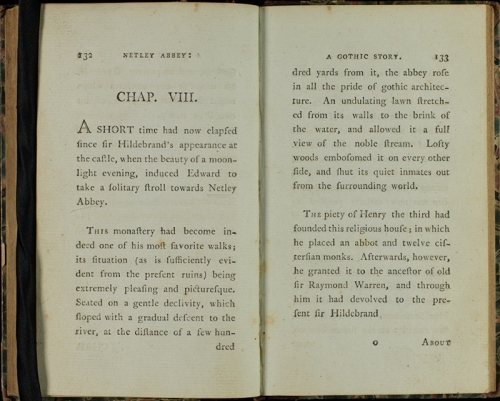

Netley Abbey: a Gothic Story, Richard Warner (Rare Books Cope NET 81 WAR)

Richard Warner’s novel Netley Abbey: a Gothic Story was published in two volumes in 1795. Warner (1763–1857) was a clergyman and writer, particularly of books on topographical and antiquarian topics. Netley Abbey, his first publication, recounts the adventures of Edward de Villars, the son of Baron de Villars, a loyal servant of Edward I. The Baron is banished from the court of Edward II after which he and his family relocate to the estate of Sir Hildebrand Warren near Netley Abbey. Edward receives a supernatural warning about sinister events taking place in the area and proceeds to encounter a host of gothic characters, including plotting villains, rescued captives, ghostly apparitions, and a mysterious black knight. The novel is formulaic and contains many of the gothic tropes and plot devices established in The Castle of Otranto. However, it does differ in the fact that, unlike Walpole and Matthew Lewis, Warner employs a real place. Matthew Woodworth notes that “it is the abbey’s architecture – the style of ruined Gothic itself – that is the most threatening character of all, constantly drenched in the menace of full moonlight.” It was the likes of Warner’s work that helped turn Netley into “a pivotal monument of the Georgian Zeitgeist.”

Given the popularity of the site as a tourist destination, guidebooks inevitable followed. A prominent example is John Bullar’s A companion in a visit to Netley Abbey, first published in 1800. Keate’s elegy can be found annexed to the early editions of the guidebook, with an advertisement in the volume noting that: “When first Mr Keate published his elegy entitled Netley Abbey, he prefixed to it a short sketch of the history of the foundation. In the present publication, that account has been considerably enlarged; and such other additions have been made, as to render it a Guide to those who may visit these beautifully situated ruins.” [A companion in a visit to Netley Abbey, John Bullar (Rare Books Cope NET 26)]. Running into nine editions, the guidebook provides topographical details, along with a history of the abbey, a number of vignettes, and a ground plan of the site.

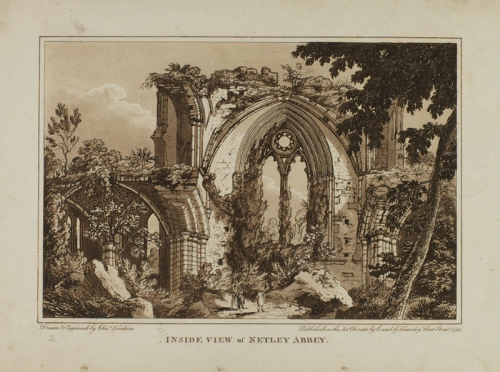

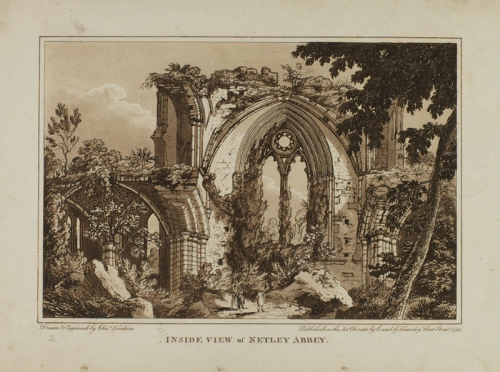

Inside view of Netley Abbey

The extremes and common tropes of the Gothic tradition made it rich territory for satire. William Pearce’s Netley Abbey: an operatic farce in two acts pokes fun at the fashion for visiting Gothics ruins, as well as the recreation of ruins (in the form of follys) on the lands of the aristocracy. The plot follows the exploits of Oakland, his daughter, Lucy, and his son, Captain Oakland, the latter of who wishes to marry the impoverished Ellen Woodbine. It transpires that Oakland is being defrauded by his agent, Rapine, who is also responsible for the fire that destroyed the Woodbine estate. The tale culminates in the Rapine being exposed and the lovers being united against the backdrop of Netley Abbey. First performed at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, in 1794, Paul Rice notes that the portrayal of the ruins of the abbey on stage in the final scene was “highly evocative and gained much audience approval.”

![Netley Abbey, Thomas Ingoldsby (Rare Books Cope quarto NET 26)]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/image-5-netley-ingoldsby.jpg?w=500)

Netley Abbey, Thomas Ingoldsby (Rare Books Cope quarto NET 26)]

Netley Abbey by Thomas Ingoldsby was first published as part of The Ingoldsby legends, or, Mirth and marvels in the 1840s. The name Thomas Ingoldsby was the pseudonym for the Reverend Richard Harris Barham (1788-1845). A writer, as well as a clergyman, he was best known for his series of myths, legends, ghost stories and poems. While his writings were based on traditional legends, Ingoldsby’s versions contain strong elements of satire and parody – with Netley Abbey being no exception:

And yet, fair Netley, as I gaze

Upon that grey and mouldering wall,

The glories of thy palmy days

Its very stones recall!–

They ‘come like shadows, so depart’–

I see thee as thou wert — and art –

Sublime in ruin!– grand in woe!

Lone refuge of the owl and bat;

No voice awakes thine echoes now!

No sound — Good Gracious!– what was that?

Was it the moan,

The parting groan

Of her who died forlorn and alone,

Embedded in mortar, and bricks, and stone?–

Full and clear On my listening ear

It comes–again–near, and more near–

Why ‘zooks! it’s the popping of Ginger Beer!

[Netley Abbey, Thomas Ingoldsby (Rare Books Cope quarto NET 26)]

The 1889 edition in the Cope collection was published posthumously with the poem accompanied by lithographic illustrations by Enest M. Jessop.

During the 20th century, changing attitudes led to the clearing of the vegetation and debris from the abbey ruins. All traces of the later alterations were removed, and the ruins were returned to their pristine state. The abbey is now an English Heritage site and continues to draw a large number of visitors every year. As part of the events for Jane Austen 200 there will be a series of lantern Halloween ghost walks at the abbey from 30 October to 1 November. Further details can be found at: https://www.sarahsiddonsfanclub.org/events/a-mystery-of-a-horrible-nature-lantern-halloween-ghost-walk/

![Photograph of S.M.Rich "in sports coat" taken in 1902 or 1903 [MS 168 AJ217/1 p. 34 (Friday 3 February)]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/ms168_aj217_1_p34_0001.jpg)

![Photograph of Samuel's wife Amy. [MS 168 AJ217/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/ms168_aj217_1_portrait_amy_0001.jpg)

![Photograph of Samuel and Amy Rich, 1901 [MS 168 AJ217/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/ms168_aj217_1_couple_1901_0001.jpg)

![Solitary reading [MS 242 A800]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/ms242_a800_p56v_0007.jpg)

![Catalogue of the Book-room at Broadlands, 1791 [MS 62 Broadlands Archives BR101/26]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/ms62_br101_26_cover_1.jpg)

![Listing of novels, including Joseph Andrews at north end of Book-room [MS 62 Broadlands Archives BR101/26]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/ms62_br101_26_fieldinglisting.jpg)

![W.B. Yeats, November 1896, The Celtic Twilights by W.B. Yeats [Rare Book X PR5704]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/rb_x_pr_5704_27547_celtic_twilight_frontispiece_0002.jpg)

![Poems by W.B. Yeats, 1865-1939 [Rare Book x PR 5902]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/rb_x_pr_5902_25341_poems_titlepage_00011.jpg)

![On the Boiler, by W.B. Yeats, 1916 [Rare book X PR 5904]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/05/rb_x_pr_5904_74483_on_the_boiler_frontcover_0001.jpg)

![The works of Sir William Temple, bart. edited by Jonathan Swift [Rare Books quarto PR 3729.T2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/works-of-sir-william-temple-3.jpg?w=500)

![Prometheus, a Poem by Jonathan Swift [BR3/36]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/prometheus-crop-2.jpg?w=500)

![Swift's signature [MS 62 BR3/63]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/signature.jpg?w=500)

![Netley Abbey, Thomas Ingoldsby (Rare Books Cope quarto NET 26)]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/image-5-netley-ingoldsby.jpg?w=500)

![Opening lines of Edmund Blunden's Portrait of a colonel [MS10 A243/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/ms10_a243_2_cropped1.jpg?w=500)

![F.T.Prince [MS328 A834/1/11/10]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/ms328_a834_1_11_10_cropped.jpg)

![Students outside a sandbag protected University College of Southampton, 4 October 1939 [MS310/43 A2038/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/ms310_a2038_2_sandbags_r_0001.jpg?w=500)

![Major Frederick Dudley Samuel [MS336 A2097/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/ms336_a2097_1_f-samuel_cropped.jpg?w=225)

![Envelope of letter from Fred Samuel to his wife, 1917 [MS336 A2097/8/2/31]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/ms336_a2097_8_2_31_env_cropped.jpg?w=500)

![Tobias Young A near view of Southampton in 1819; taken from the banks of the canal near the tunnel (1819) in Cope, Sir W.H. Views in Hampshire, v.4: illus. 116 [Rare Books Cope ff 91.5]. Castle Square is thought to be the large house with tall chimneys in front of the castle.](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/illus1.jpg?w=500)

![T.H. Skelton All Saints Church (Southampton, 1811) [Rare Books Cope c SOU 26 pr.832]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/illus2.jpg?w=500)

![Southampton in 1806 in The Southampton Atlas (Southampton, 1907) [Cope ff SOU 90.5]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/illus3-map.jpg?w=500)

![T. Younge A view of the New Bridge at Northam (c.1797) [Rare Book Cope c SOU 43 pr.845]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/northam_bridge.jpg?w=500)

![The Southampton Guide (Southampton, 1806) [Rare Books Cope SOU 03.5 1806]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/illus4.jpg?w=500)

![John Hassell Netley Abbey (London, 1807) [Rare Books Cope c NET 26 pr.669]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/illus5.jpg?w=500)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)