On St Patrick’s day we mark the anniversary of the arrival of the Wellington Archive at Southampton in 1983. Since then, the Special Collections has acquired a wide range of material that relates to this archive and we take the opportunity to explore some of these.

Part of Wellington Archive

The Wellington Archive [MS61] represents the political, military and official papers of Wellington, so collections that provide a more personal perspective on the Duke are always of interest. Christopher Collins entered Wellington’s service in 1824 and worked as his confidential servant for the remainder of the Duke’s life. Amongst the papers in this collection [MS69] are notes and letters from the Duke issuing instructions about ordering straps with buckles and boots, arrangements for mending razors, for preparations for his room at Walmer Castle and the cleaning and maintenance of uniforms.

![Note from Wellington to Collins sending instructions for preparing his room at Walmer Castle, 1838 [MS69/2/15]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms69_2_15_crop.jpg)

Note from Wellington to Collins sending instructions for preparing his room at Walmer Castle, 13 September 1839 [MS69/2/15]: “have some fire in my room; some hot water for tea; and some boiling sea water for my feet”.

Collins kept a notebook listing the Duke’s diamonds, ceremonial collars, field marshal batons and coronation staves, 1842 [MS69/2/1] and amongst the objects in the collection are the blue ribbon of the Order of the Fleece and the red ribbon of the Order of the Bath which belonged to Wellington [MS69/4/11-12].

![Red ribbon of the Order of the Bath [MS69/4/11]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms69_4_11.jpg)

Red ribbon of the Order of the Bath [MS69/4/11]

Collins also kept notes on Wellington’s health [MS69/2/3] and the collection includes a number of recipes, such as one for “onion porage” to cure “spasms of the chest and stomach”, 1850, below.

![Recipe for "onion porage" [MS69/4/19]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms69_4_19r.jpg?w=500)

Recipe for “onion porage” [MS69/4/19]

Three letters from Wellington to William Holmes, Tory Whip, in December 1838 [MS272/1 A9231/-3], likewise deal with the Duke’s health and in particular reports in the

Morning Post about this. The Duke complained in a letter of 22 December 1838: “If people would only allow me to

die and be damned I should not care what the

Morning Post thinks proper to publish. But every

devil who wants anything writes to enquire how I am.”

A small series of correspondence of Wellington, and Deputy Commissary General William Booth, which is a more recent acquisition, provide some insight into the management of Wellington’s estates at Waterloo, 1832-52 [MS414].

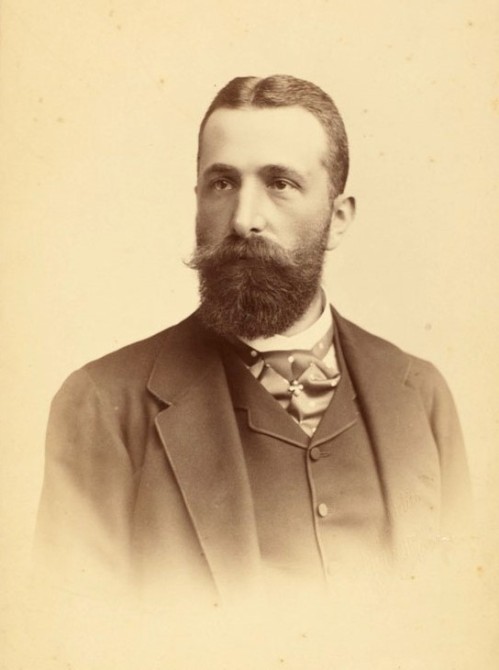

![Illustration of the Duke of Wellington [MS351 A4170/9]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms351_6_a4170_9.jpg?w=500)

Illustration of the Duke of Wellington [MS351 A4170/9]

A number of military archive collections, including some of officers who served with Wellington, now join company with the Wellington Archive at Southampton. Papers of Sir John Malcolm, 1801-16, [

MS308] provide important evidence for Wellington in India, at a formative stage of his career, in comparatively informal and personal correspondence with a friend and political colleague; it includes Wellington’s letters written in the field throughout the Assaye campaign.

MS321 is composed of seven volumes of guardbooks of correspondence and papers of Lieutenant Colonel John Gurwood, who was editor of Wellington’s

General Orders and

Dispatches. The collection relates to Gurwood’s military career as well as his editorial work.

![Letter from Gurwood to his mother in which he reports he led the "forlorn hope" at Ciudad Rodrigo, 20 January 1812 [MS321/7]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms321_5_20jan1812_0001.jpg?w=500)

Letter from Gurwood to his mother in which he reports he led the “forlorn hope” at Ciudad Rodrigo, 20 January 1812 [MS321/7]

Sir Robert Hugh Kennedy served as Commissary General of the forces commanded by Wellington in the Iberian Peninsula, with Sir John Bisset serving in Kennedy’s stead in 1812, and their collection of letter books, accounts and other papers cover the period 1793-1830 [

MS271], providing evidence of the work of this department during military campaigns over this period. An order book of the general orders of Sir Edward Barnes, Adjutant General of the army in Europe, 10 May 1815 – 18 January 1816, covers the period of the battle of Waterloo and the allied occupation of France [

MS289]. And the diary of George Eastlake, recording a visit to northern Spain with Admiral Sir Thomas Byam Martin in September 1813 to discover Wellington’s requirements for naval assistance, provides details of Wellington’s headquarters at Lesaca as well as the army camp at Bidassoa [

MS213].

A journal sent by General Francisco Copons y Navia to the Duke of Wellington details the operations undertaken by the Spanish First Army for the period 2-20 June 1813 in relation to those of General Sir John Murray. Murray had landed with a British force at Salou in Catalonia on 3 June and laid siege to Tarragona [MS253].

!["Journal du blocure de la place de Barcelonne" [MS360/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms360_1_f1r_crop.jpg)

‘Journal du blocure de la place de Barcelonne’ [MS360/1]

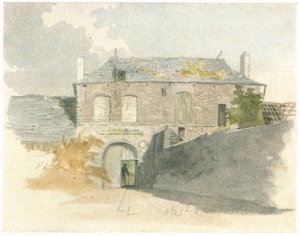

Formerly part of a larger series of documents, Special Collections holds two booklets, signed by F.Mongeur, the Commissaire Ordonnateur for Barcelona, at Perpignan on 3 June 1814, that relate to the administration of Barcelona in 1814. The first, the ‘Journal du blocure de la place de Barcelonne’ has a daily record from 1 February to 3 June 1814 of the French forces [

MS360/1]. The succeeding document in the series is a general report, in French, on the administration of the siege of Barcelona by the armée d’Aragon et de Catalogne, between 1 January and 28 May 1814, which gives details of the period of the evacuation of the place, as well as of the food and consumption of foodstuffs and expenditure on supplies during this period. There is a detailed analysis of the composition of the forces, the different corps of troops, companies and detachments making up the garrison at Barcelona [MS360/2].

![Signature of Daniel O'Connell, 1815 [MS64/17/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms64_17_2_signature_1.jpg?w=500)

Signature of Daniel O’Connell, 1815 [MS64/17/2]

Material relating to politics in the Wellington Archive is paralleled by that within a number of significant other collections at Southampton. The archive of the Parnell family, Barons Congleton [

MS64] which contains extensive material relating to Irish politics. Amongst the papers of Sir John Parnell, second Baronet, is material for the Union of Ireland and Great Britain, whilst the papers of the first Baron Congleton include material about Roman Catholic emancipation.

![Letter from Daniel O'Connell to Sir Henry Parnell, 13 June 1815 [MS64/17/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms64_17_2_cover_crop.jpg)

Letter from Daniel O’Connell to Sir Henry Parnell, 13 June 1815, relating to Catholic emancipation [MS64/17/2]

The Broadlands Archives [

MS62] also contain much on British and Irish politics in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as well as papers of two nineteenth-century Prime Ministers in the form of Lords Palmerston and Melbourne. A collection of correspondence between John Wilson Croker and Palmerston for the period 1810-56 [

MS273] includes much on political, military and official business. Papers of Wellington’s elder brother, Richard, Marquis Wellesley, include material relating to his tenure as ambassador in Spain, 1809, and as Foreign Secretary, 1809-12 [

MS63].

![Letter from Simon Bolivar to Lord Wellesley, 22 January 1811 [MS63/9/7]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms63972.jpg?w=500)

Letter from Simon Bolivar to Lord Wellesley, 22 January 1811 [MS63/9/7]

Since its arrival in 1983, which also heralded the development of the Archives and Manuscripts as a service, the Wellington Archive has acted as an irresistible draw to other collections to join its company.

To find out more about Wellington, or research that has drawn on the collections held at Southampton, why not join us at this year’s Wellington Congress. Registration is open until the end of March.

![Photograph of Richard Cockle Lucas taken by himself [rare books Cope 73 LUC O/S13789]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/cope_73_luc_album2_p29v_0001.jpg)

![Tower of the Winds photographed by Lucas in 1864 [rare books Cope 73 LUC O/S13788]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/cope_73_luc_album1_p5_0001.jpg?w=500)

![Major Frederick Dudley Samuel [MS336 A2097/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/ms336_a2097_1_f-samuel_cropped.jpg)

![Note from Wellington to Collins sending instructions for preparing his room at Walmer Castle, 1838 [MS69/2/15]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms69_2_15_crop.jpg)

![Red ribbon of the Order of the Bath [MS69/4/11]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms69_4_11.jpg)

![Recipe for "onion porage" [MS69/4/19]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms69_4_19r.jpg?w=500)

![Illustration of the Duke of Wellington [MS351 A4170/9]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms351_6_a4170_9.jpg?w=500)

![Letter from Gurwood to his mother in which he reports he led the "forlorn hope" at Ciudad Rodrigo, 20 January 1812 [MS321/7]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms321_5_20jan1812_0001.jpg?w=500)

!["Journal du blocure de la place de Barcelonne" [MS360/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms360_1_f1r_crop.jpg)

![Signature of Daniel O'Connell, 1815 [MS64/17/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms64_17_2_signature_1.jpg?w=500)

![Letter from Daniel O'Connell to Sir Henry Parnell, 13 June 1815 [MS64/17/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms64_17_2_cover_crop.jpg)

![Letter from Simon Bolivar to Lord Wellesley, 22 January 1811 [MS63/9/7]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/03/ms63972.jpg?w=500)

![Sir Denis Pack [MS296 A4298]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/pack_crop.jpg)

![Detail from map of Battle of Busaco [MS296 A4298]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/busaco_detail.jpg)

![Manuscript map of the battle of Salamanca, 1812 [MS296 A4298]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/salamanca_map.jpg)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)