Father’s Day, celebrated in the United Kingdom on the third Sunday of June, is a day of honoring fatherhood and paternal bonds, as well as the influence of fathers in society. Unlike Mothering Sunday, which most historians believe evolved from a medieval practice of visiting one’s mother church during Lent, Father’s Day does not have a long tradition.

This year, to celebrate Father’s Day, we delve into the extensive resource that is the Broadlands Archives; this collection contains dozens of letters between Henry Temple, the second Viscount Palmerston, and his four children. Henry’s first child (also called Henry) was born in 1784. As Father’s Day is a twentieth century phenomenon, the Temple family would not have celebrated it. Despite the letters being over 200 years old, many themes are remarkably similar to modern day life and provide a wonderful vignette of Georgian family life.

![Broadlands printed by Ackermann [Cope Collection]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2021/06/cq_72_bro_pr_41_0005-2-edited.jpg)

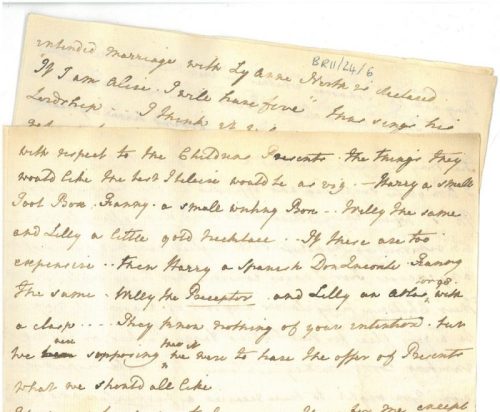

Henry Temple, second Viscount Palmerston was born in 1739. He married Mary Mee in 1783 and they had 4 (surviving) children: Henry, Frances, William and Elizabeth. In a letter to her husband, sent from Broadlands on 26 December 1788, Mary says:

Harry sends his love, and will kiss the letter, which he thinks the only way of sending a kiss, and Fanny ditto

MS62/BR/11/13/15

The future third Viscount Palmerston would have been about 4 at the time and his younger sister, Frances, just 2. If you note the date, it seems that Father’s Day was not the only celebration that had less significant status in the late eighteenth century!

The Temples spent a fair amount of time apart: probably not uncommon for a noble family in this period. Many of their frequent letters have been preserved, leaving a wonderfully rich resource for historians. Lady Palmerston went to Bath in January 1795 to stay with her ill mother. Lord Palmerston had all the children to live with him at their London residence in Hanover Square and sent regular domestic news to his wife:

Lilly’s cough has been nothing and only seemed to come at times and then was gone and then it came again but Mr Walker thought her bowels wanted clearing which might have something to do with her coughing. She has taken twice calomel which has had a very happy effect and she seems very well…

I will do something about a dentist. I have been talking with two or three people and for the present am inclined to apply to Spence as I understand that he is much used to childrens teeth about the time of changing them and that as some drawing may be requisite he is superior to any body in the respect.

MS62/BR/20/11/2

His remarks are strangely reminiscent of twenty-first century family life, if the medical treatments have advanced somewhat in two centuries! A subsequent letter sends good news respecting the dreaded dental appointment:

I am very happy to tell you that poor Fanny muster’d up a great deal of courage today and has had one tooth out which is what Spence thought most immediately necessary and she says it did not give her near so much pain as she expected and that she shall not much mind having the others out when it is necessary.

MS62/BR/20/11/1

Later that same year in May, Lord Palmerston updates his wife that: “the boys are well but I never – but for a moment – see them as their hours are so different that I have no means of doing so, not dining at home, without deranging their studies or their amusements either of which I shd be sorry to do.” [BR20/12/40] Their eldest son would have been about eleven years old at this point and just about to start at boarding school, as we learn in the next letter.

I drove down to Harrow yesterday and had some conversation with Mr and Mrs Bromley. She seems very intelligent and notable and I dare say will take very good care of Harry… They do not wish for more clothes than are likely to be useful… I forgot to ask them about night shirts but I am persuaded they are quite out of the question and wd only make him the joke of the other boys.

Letter from Henry Temple, second Viscount Palmerston, London, to Mary Mee, Clifton, Bristol MS62/BR20/12/41

Harry was later persuaded that a night shirt might be a good idea. We are sure many parents of teenage children have had a similar battle respecting winter coats! The following year, December 1796, Lord Palmerston writes from their London home in Hanover Square to his daughter Lilly:

My dear Lilly

I am much obliged to you for your nice and well written Italian letter. I am very glad to hear that you and your brother and sister are well, and that you have nursed your mama so well…Miss Carter…is much delighted with your theatre, and says you are an excellent little actress… I hope you will not get cold this very severe weather. It freezes here uncommonly hard for the time of year… All the London ice houses are filling up and the ice is two or three inches thick…

Give my best love to all your party and believe me ever

My dear little Lilly

Your affectionate Father

Palmerston

MS62/BR6/3/9

Lord and Lady Palmerston decided to place their eldest son, now fifteen years old, in an intermediary situation between school and an English university. When Lord Palmerston writes to the proposed new tutor Dugald Stewart he acknowledged that his “father’s account” of his son’s character may not be impartial:

My son who was fifteen years of age last October has risen nearly to the top of Harrow School and has given me uniform satisfaction with regard to his disposition his capacity and his acquirements. He is now coming to that critical and important period when a young man’s mind is most open to receive such impressions as may operate powerfully on his character and his happiness during the remainder of his life … I would be cautious of saying thus much in his commendation if it was likely you would have much opportunity on enquiring what he is from others; but as that may probably not be the case, you must, in default of more impartial judges, accept a father’s account with such allowance as you may think proper to make.

[Jun 1800 MS62/BR12/1/4/1]

The tender care and fatherly pride is plainly evident through all of Lord Palmerston’s correspondence with his children. He died two years later aged only 63 leaving his son Henry to inherit his title and become the third Viscount Palmerston.

Many of you will be well aware that commemorative days are not always easy, particularly for children who have lost their father; fathers who have lost children and those who would have loved to have been a father, but never had the opportunity. We would like to take this opportunity to wish all the fathers, and others who take a paternal role in the lives of others, a very happy Fathers Day.

![Lord Palmerston as an elder statesman, West Front, Broadlands: an albumen print probably from the 1850s [MS 62 Broadlands Archives BR22(i)/17]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/09/palmerston-broadlands.jpg?w=235)

![‘Plan of the city of Lima, capital of Peru’: taken from A compendium of authentic and entertaining voyages (second edition, London 1766) vol. 2 [Rare Books G 160]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/g160-pg221-open_0010lima_cropped1.jpg?w=300)

![This watercolour of Malta is from the sketch book of Julia (Sissy) Matilda Cohen during a cruise around the Mediterranean in 1895 [MS 363 A3006/3/5/6]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/ms363_a3006_3_5_6_cropped.jpg?w=300)

![Volume 1 of Louis Arthur Lucas’ African sketch book: huts of the Kytch tribe, [Southern Sudan], 1876 [MS 371 A3042/2/6/14]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/ms371_a3042_2_6_14_p41cropped.jpg?w=500)

![Page of a note from Sir J.Willoughby Gordon to Arthur Wellesley, first Duke of Wellington, sending a detailed report of the journey of Gurney's steam carriage from London to Bath, 31 July 1829 [MS 61 Wellington Papers 1/1034/29]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/ms61_wp1_1034_29_cropped.jpg?w=500)

![Letter from William Temple, Munich, to his mother Mary (Mee), Viscountess Palmerston, 11 July [1794]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/ms62_br32_1_1.jpg?w=300)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)