And so we move to the “swinging sixties”, a decade of significant growth and expansion for the University. Projections made at the beginning of the 1960s were that Southampton would reach a total of 4,000 students by 1980. However, in 1963 the Robbins Report was published. This proposed great expansion in higher education and recommended that the number of students at English Universities should rise from 150,000 to 170,000. Southampton seized this opportunity and offered to increase its students to 4,000 by 1967.

Aerial view of the Highfield site, c. 1959 [MS 1/Phot/11/5] University Road runs past the ‘main building’ [now the Hartley Library]

Key to the 1960s was architect Sir Basil Spence who had been charged the previous decade with creating a “master plan” for the Highfield Campus and all the major buildings of this period were designed by him.

[MS 1/Phot/39 ph3375]

The Arts

In the pre-war era Arts had been a small part of what was primarily a science, engineering and teacher training college. In the 1960s, the General Degree was replaced with a new Combined Honours Degree. The following year, 1963, the Arts 1 Building was completed as part of the “Nuffield complex”; this building is now used by the Law School.

Arts I, 1969 [MS 1/Phot/22/3/2]

The Department of Archaeology was established in 1966. The chair was given to Barry Cunliffe who, aged 26, was believed to be the youngest professor the college or university had ever appointed. The Modern Languages Department transferred its teaching of languages for non-specialists to a new language centre under Tom Carter, with two language laboratories. The Library hold some records of the Modern Language Society in MS 1 A308.

Arts II and the Nuffield Theatre [MS 1/Phot/22/3/2]

Arts II [MS 1/Phot/22/3/2]

In 1961 Peter Evans was appointed first Professor of Music since 1928. He engineered the virtual creation of a Music Department involved in the academic study of music as well as a huge expansion of live performance.

Science

The Science Faculty had 1,522 applicants for admission in October 1960; it was only permitted to take 160. As a result of the Robbins Report, the University appointed 11 Professors to the Faculty: four to arrive 1967-8 and the other seven the following year.

To help with expansion, new accommodation was built for the Chemistry department in 1960-1. It was later to be named after Graham Hill, Chair of Chemistry for some 18 years.

Graham Hill building [MS 1/Phot/37/7]

Chemistry department teaching laboratory, 1969 [MS 1/Phot/12/11]

Oceanography had its origins in the Department of Zoology. As an embryonic department it was promoted with enthusiasm by Professor John Raymont: he started researching the marine biology of coastal waters using Zoology’s first boat Aurelia. Oceanography became a separate department in October 1964 and John Raymont became Professor of Biological Oceanography. A new building north of the campus on Burgess Road was completed in 1965; designed in brick by the Sheppard Robson Partnership. Since 1996 this has housed part of Electronics and Computer Science.

Construction of the Oceanography Building, October 1964 [MS 1/Phot/22/1/3/16]

Construction of the Shackleton building, April 1966 [MS 1/Phot/22/1/2/23]

Physics building with the Mathematics building in the background, late 1960s [MS 1/Phot/22/3/2]

Engineering and Applied Science

The Lanchester and Tizard buildings for Engineering, Electronics and Aerospace studies were opened in May 1960. They were located on the north of ‘Engineering square’ and connected to the pre-existing engineering facilities.

Lanchester Building from the South East [MS 1/Phot22/1/3]

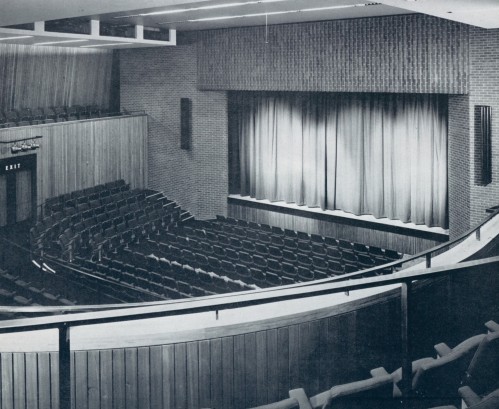

Main lecture theatre in the Lanchester Building [MS 1/Phot22/1/3]

Official opening of the Lanchester building in May 1960. L-R: Vice Chancellor, Mrs D.Lanchester (widow), Mr. Lanchester (brother), Sir George Edwards, Lady Tizard, Lady Edards, Mrs James and Dr Tizard [MS 1/Phot/39 ph3200]

Engineering department [MS 1/Phot/22/2/1/3]

The faculty received an extension in 1968 with the Wolfson and Raleigh buildings.

View of Lanchester Building and Faraday Tower, 1970 [MS 1/Phot/22/3/2156]

Fan noise measurement at the Institute of Sound and Vibration Research, c. 1960s or 1970s [MS 1/Phot/11/29]

Computation laboratory, 1961 [MS 1/Phot/11/31]

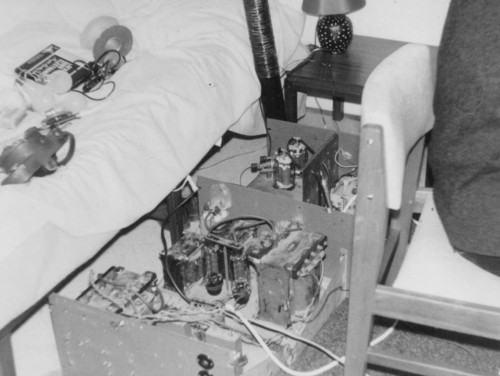

Memory store for Pegasus computer, 1961 [MS 1/Phot/11/31]

Medicine

The University had a medicine-related Department of Physiology and Biochemistry. In 1967, the Royal Commission on Medical Education advised the Government that there was a strong case for establishing a new medical school in Southampton. The previous year it had established that there needed to be an immediate and substantial increase in the number of doctors. Sir Kenneth Mather, (Vice Chancellor 1965-71) whose specialism was genetics, had been an enthusiastic supporter of the project.

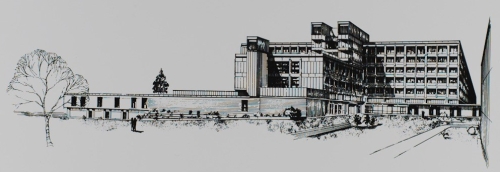

Sketch of the proposed Medical and Biological Sciences building from the south, c. 1960s [MS 1/Phot/39 ph3228]

Social Sciences

Economics was transformed into the Faculty of Social Sciences in 1962. It was divided into 5 departments: Economics, Sociology and Social Studies, Politics, Economic Statistics and Commerce and Accounting.

The Mathematics tower was built in 1963-5 by Ronald H Sims in the “brutalist style” with exposed concrete.

Photograph of the Maths building at the Highfield site, c. 1965-70 [MS 1/Phot/11/10]

Examination papers from the period are preserved in our strongrooms: do you think you would pass?

Mathematics examination paper, 1960s [MS 1 A2060]

Halls of residence

As a consequence of growth, the percentage of students living in halls of residence had fallen from 46 percent to 37 percent. Long-standing Council member, James Matthews, had convinced the University that the growing student body would require more accommodation and set about acquiring the first essential: land. The University bought 4 acres of land at the junction of Burgess Road and the Avenue and were also given the right to acquire some 200 houses on or near the campus, all for subsequent demolition to release their sites.

The East Wing of Chamberlain Hall [MS 1/Phot22/1/1/8]

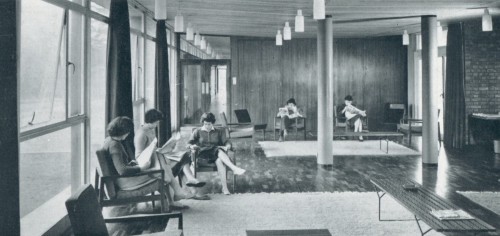

The Junior Common Room of Chamberlain Hall [MS 1/Phot22/1/1/8]

Construction of South Stoneham House, May 1962 [MS 1/Phot/11/20]

Montefiore House (often referred to as ‘Monte’) as a hall of residence was opened in 1966, built on the grounds of the sports field.

Construction of Montefiore House Blocks A and B, 1964-5 [MS 1/Phot/22/1/7]

New Court at Glen Eyre Hall of Residence, 1969 [MS 1/Phot/22/3/3]

Professional Support Services: the Library, Computing Services and Administration

At this time, the ‘Main Building’ housed not only the Library, but also Administration and provided classrooms for several faculties. The Gurney-Dixon link had opened at the very end of the last decade, December 1959. This provided a large extension to the original pre-war building. At the start of the decade there was space for 250,000 books and periodicals and 550 readers.

Level four of the Gurney-Dixon link, looking west showing card catalogues and Library counter staff with Mrs S.Bell, Library Assistant; Miss E.Fitzpayne; Miss M.Cooper, Senior Library Assistant and Miss A.Player, August 1966 [MS 1/Phot/39 ph3262]

The proportion of students using the Main Library much for borrowing (2 or more books a week) ranged from 52% in Arts to 0% in Engineering; Economics, with 19%, had the second highest proportion. […] In all faculties the proportion of students using the Main Library for working with their own books was high […] and 21% used it for “other purposes” (e.g. letter writing).

28% of the sample used the catalogues as a first resort, 13% never used them if they could help it.

65% found the Library staff always ready to help, 22% helpful but not always available, and 3% not helpful […]It had never occured to over half the students that the staff could help them with a subject inquiry […]

MS 1/5/239/129

A great coup for the University was the acquisition of the Parkes Library. It was originally the private library of Revd. Dr James Parkes (1896-1981) who devoted his life to investigating and combating the problem of anti-Semitism. Parkes began collecting books whilst working for the International Student Service in Europe during the 1930s. On his return to Britain in 1935, following an attempt on his life by the Nazis, he made the collection available to other scholars at his home in Barley near Cambridge.

The official opening of the Parkes Library showing an exhibition in the Turner Sims Library, 23 June 1965 [MS 1/Phot/39 ph3513]

It was in the 1964-5 session that Geoff Hampson was appointed Assistant Librarian in charge of the Special Collections and Archives; at the same time, a “suitable repository” was established for the material. In addition, the Library was also one of the first in the country to introduce a computer-based issue system, using punched cards.

In 1967 the Computing Services was set up as a service operation outside the Mathematics Department: not for research into computing as a science, but for serving the University. The University had acquired its first computer the previous decade.

The department moved from the Library to its own purpose-built building in 1969: it was already too small to accommodate the growing number of staff.

The Arts

The Union organised the first Arts Festival, opened in March 1961 by Sir Basil Spence. In 1962-3 the Theatre Group’s Volpone was one of 5 finalists in The Sunday Times drama festival.

University of Southampton Operatic Society production of The Mikado in the University Assembly Hall in February 1960 [MS 1/7/198/1]

The Nuffield Theatre

The Nuffield Theatre was designed by Basil Spence and officially opened by Dame Sybil Thorndike on 2 March 1964.

Nuffield Theatre and sculpture in ornamental pond [MS 1/Phot/22/1/2/15]

In 1967, John Sweetman was appointed first lecturer in Fine Art. He had three responsibilities: to organise art exhibitions, to manage the University’s permanent art collection and to lecture on the history of art. The gallery in the Nuffield was far from satisfactory, with windows on three sides which had to be blacked out, but Sweetman managed to organise three exhibitions a term. From 1967 a succession of Fine Arts Fellows (among them Ned Hoskins and Ray Smith) spent periods at the University where they were given studios and provided general support to its cultural life.

Student life

By 1960-1 the Union had expanded into almost the whole of the “West Building” – the Old Union Building – dating back to the 1940s, in red brick style. By 1967 the new Students’ Union building was completed, in the Basil Spence masterplan, offering on-site catering, shopping, indoor sports and a debating chamber for the first time. The two buildings were connected by an underground tunnel.

The bar in the Students’ Union, c. 1970 [MS 1/Phot/22/3/2]

The refectory in the new Union building, c. 1970 [MS 1/Phot/22/3/2]

Gymnasium and sports hall, 1970 [MS 1/Phot/22/3/2]

“Radio Goblio” RAG, 1964 [MS 310/80 A4150]

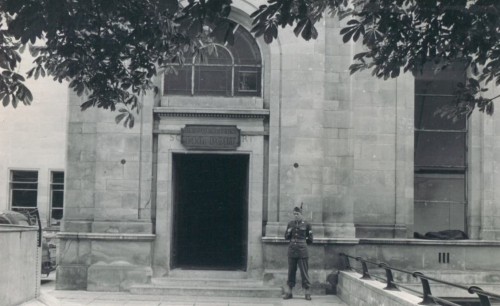

George Walker protest SCR, 19 May 1965 [MS 310/80 A4150]

This period also saw the establishment of a student health centre with a sick bay at Chamberlain Hall.

Sport

The University boat club was one of the many sporting activities in which Southampton students could choose to partake in this decade. Others included rugby, basketball, hockey, lacrosse and squash.

The first VIII at Cobden Bridge, March 1961 [MS 310/46 A2075]

As we draw this long post to a close, it is obvious that so much was achieved during this decade. The University saw incredible expansion in the sixties: the institution truly seized the opportunities offered by the Robbins report with both hands. Look out for our next post to read the next chapter in the University’s history and learn about the challenges and opportunities brought by the 1970s.

Aerial view of the Highfield site in 1970 [MS 1/Phot/11/8]. Compare this view to the one at the start of the post: the University saw incredible expansion in just 10 years!

![Major Frederick Dudley Samuel [MS336 A2097/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/08/ms336_a2097_1_f-samuel_cropped.jpg?w=380&h=507)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)