Between February and April of this year Archives and Special Collections we were joined by Ma Xiu, a student studying for a MA in the Archaeology Department, as part of her professional placement in the cultural heritage sector. Ma learned about curation of archival material through her work transcribing the field logbooks of Honor Frost. This material included excavation notes, photographs and correspondence with Frost’s colleagues, in particular her work at Alexandria in Egypt.

I have been working for the Archives and Special Collections department of the Hartley Library at the University of Southampton. I’m focused on materials from one of the archival collections, the Honor Frost Archive (MS439). My main role includes transcribing Frost’s fieldwork reports and other documents, aiming to clarify the context of archival material and enhance its accessibility.

Honor Frost was a pioneering figure in underwater archaeology, noted for her groundbreaking work in the Mediterranean. Born in 1917, she transitioned from a career in art to archaeology, where she applied rigorous scientific methods to the study of submerged historical sites, notably around Alexandria, Egypt. Her contributions set new standards in the field, and her legacy continues through her writings and the Honor Frost Foundation, establishing her as a foundational figure in maritime archaeological research.

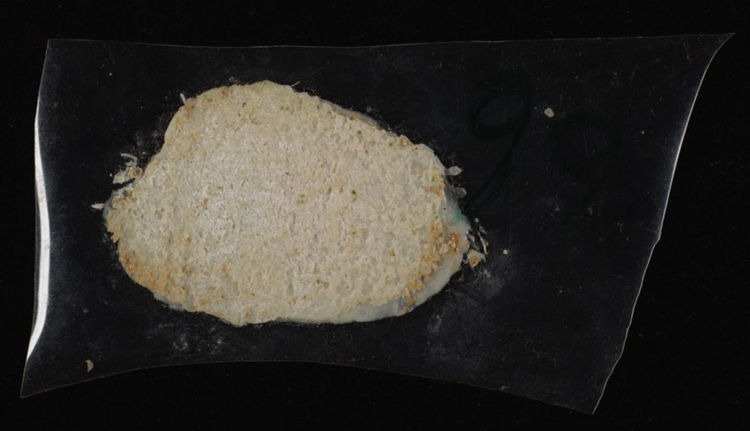

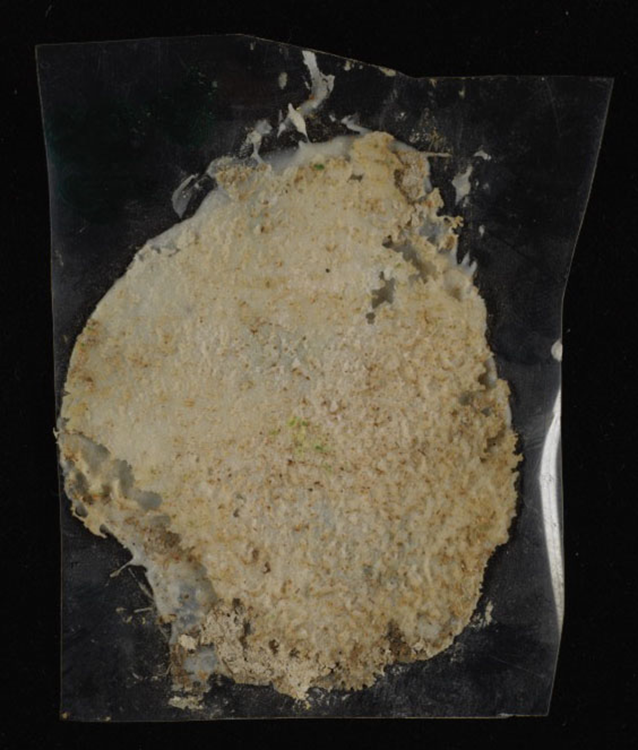

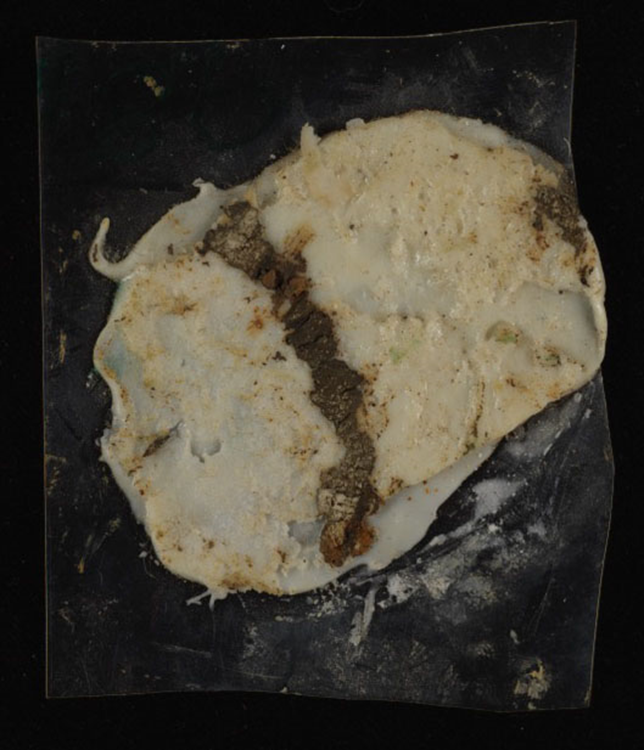

Honor Frost’s contributions to maritime archaeology are particularly evident in her studies of the submerged sites at Alexandria. The reports filed under MS439/A4278/HFA/1/3/3 are a testament to her dedication and keen analytical skills. During her dives in 1968, Frost investigated the underwater ruins at sites like Silsila and Kait Bey, revealing the remnants of ancient structures that might very well be linked to the legendary Pharos of Alexandria or other significant historical edifices. These typewritten reports, painstakingly detailed, provide insights into the methodologies employed by Frost and her team, including stone sampling and careful observation of the underwater ruins’ layout and materials. The documents not only outline the findings from these dives but also include Frost’s recommendations for future archaeological undertakings.

Silsila Site:

Description and Findings: This location contains a complex of ruined buildings, evidenced by the presence of limestone masonry, columns, and other architectural fragments scattered across the seabed. The initial dive revealed the foundation of buildings, with granite and potentially marble components, indicating substantial structures once stood here.

Challenges and Recommendations: The site’s examination was hampered by sea conditions and the lack of adequate diving equipment. Honor Frost recommended the procurement of basic diving equipment for more thorough investigation and stressed the archaeological significance of the site, suggesting that further, more detailed exploration could yield significant historical data.

Kait Bey Site:

Description and Findings: The area shows colossal masonry and orderly ruins, suggesting a single significant building, likely collapsed due to an earthquake. Elements like statues, inscriptions, and architectural orders indicate this could be part of the ancient Pharos or a related temple structure.

Challenges and Recommendations: Similar to Silsila, the exploration was limited by visibility and equipment. The report suggests international interest and potential for excavation could make deeper investigation feasible. However, there are health risks due to pollution, and Frost suggests working conditions need to be improved for any substantial archaeological work.

General Recommendations:

1. Honor Frost recommends international collaboration for the excavation and study due to the potential historical significance.

2. She highlights the health risks from polluted waters and suggests solutions like adjusting work schedules or extending sewer pipes.

3. The necessity of proper equipment and professional salvage firms for lifting heavy masonry and ensuring efficient, safe excavation processes is emphasized.

4. The potential archaeological value justifies the cost and effort of excavation, with suggestions for UNESCO sponsorship and international funding.

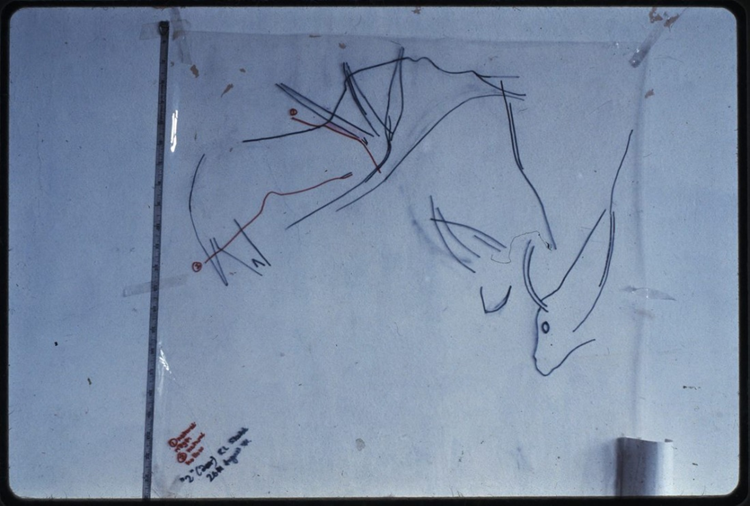

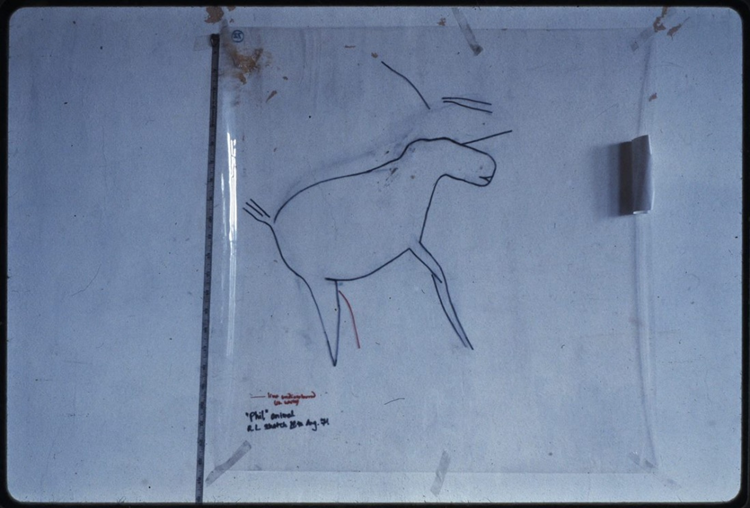

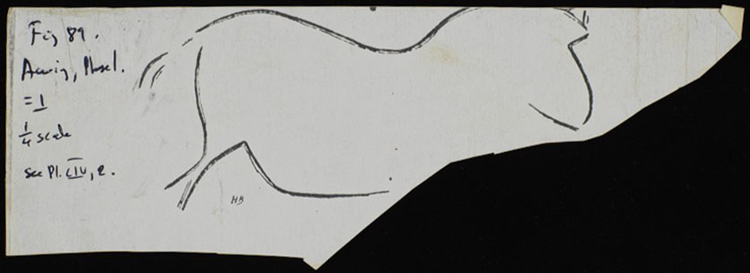

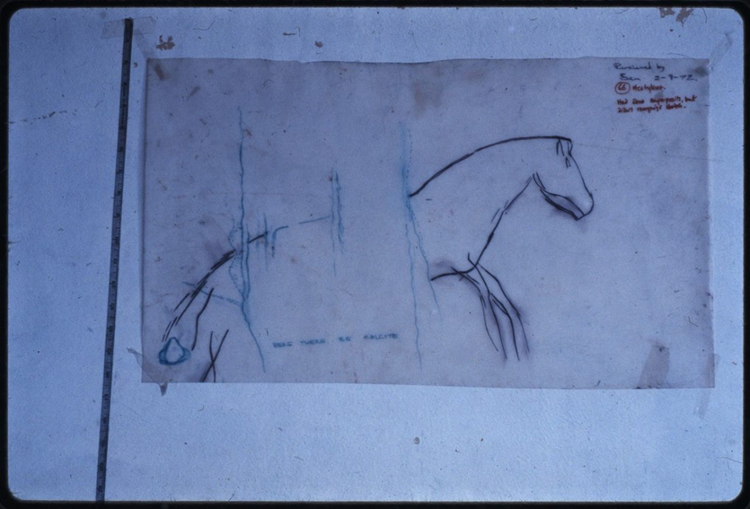

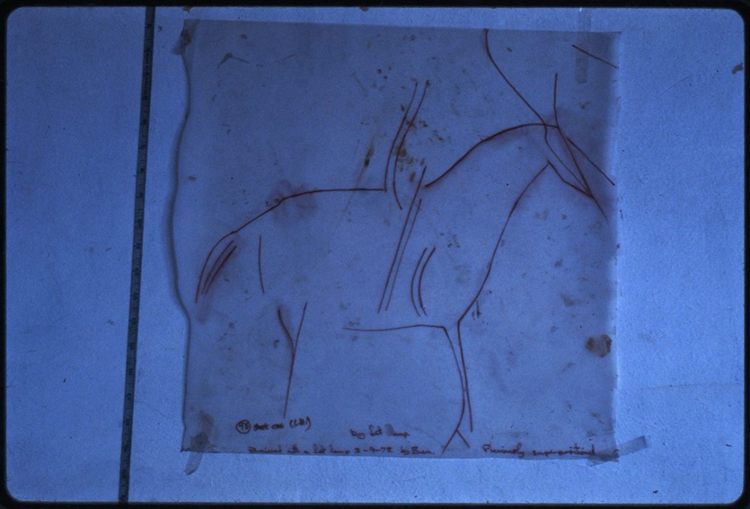

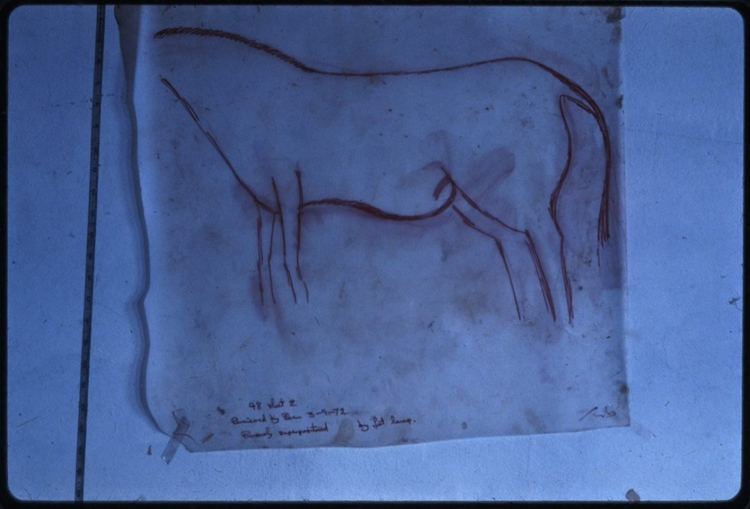

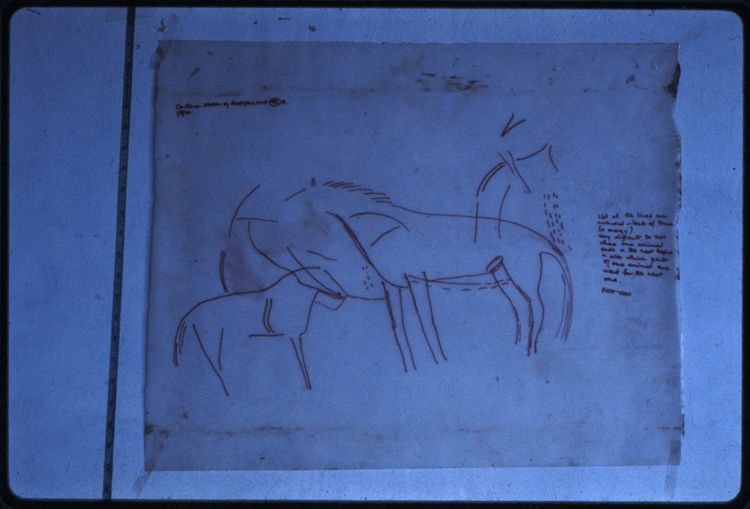

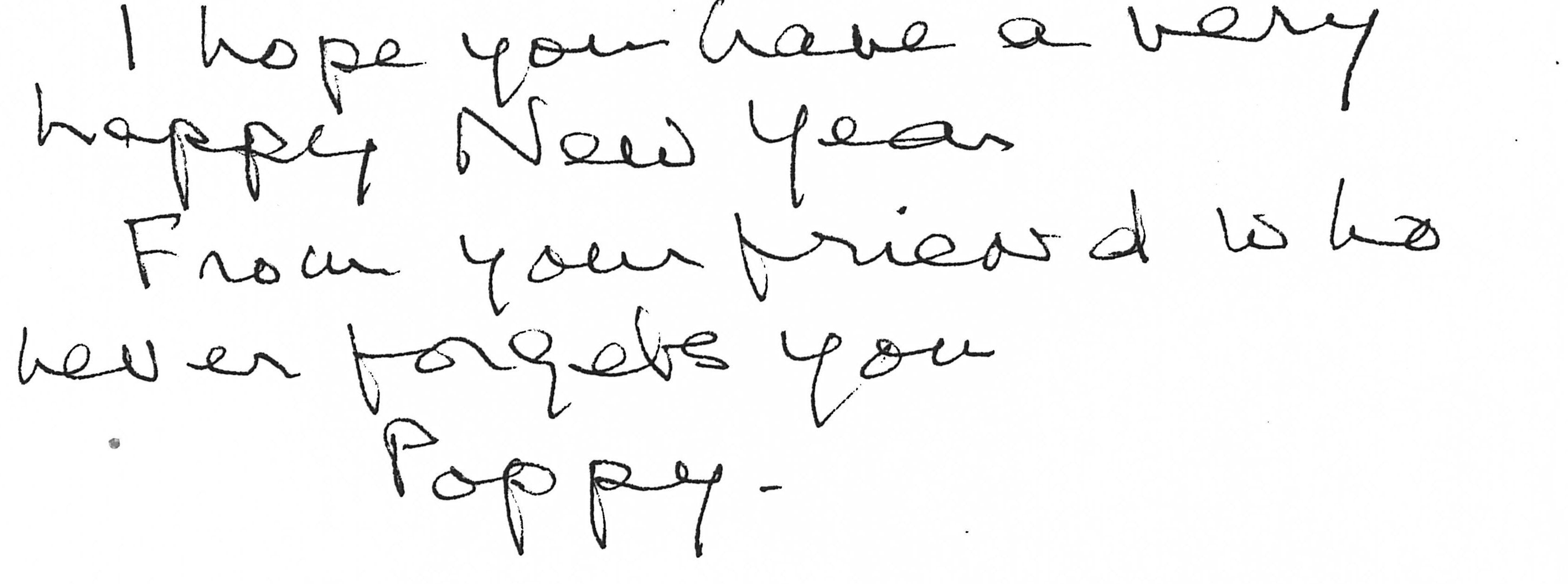

Currently, my work involves the transcription of six field logbooks that document Honor Frost’s fieldwork on the Pharos of Alexandria, recorded under MS439/A4278/HFA/1/3/1. These logbooks include letters, sketches, drawings, and photographs, which make the transcription process more vivid and narrative-driven. At the same time, challenges to my transcription work include the presence of French-language terms, cursive handwriting, and abbreviations.

The first transcript I produced corresponds to Honor Frost’s field log from her 2005 expeditions and interactions, primarily focused on archaeological investigations in the region encompassing Alexandria, Beirut, and other locations.

Field Log Structure:

Correspondence: Two Letters between Frost and Dr. Jean-Yves Empereur discuss plans for archaeological site visits and studies, particularly in Alexandria. One letter is from a correspondent named Anne Marie.

Log Entries: Daily entries from 15 to 20 September 2005, describe her activities, visits to archaeological sites, interactions with colleagues, and the logistical challenges encountered, such as obtaining permits for site photography.

Useful information: Information about Alexandria, such as maps, attractions, rental fees and numbers and addresses for academics and institutions in Alexandria.

Colour photograph of a historical map of Port Alexandria [MS439/A4278/HFA/8/3/13/496]

Overall, Karen and Russell’s kindness and enthusiasm made my work in the Archives and Special Collections Department smoother than expected. Reflecting on my experience, I realize the significance of Frost’s legacy that goes beyond maritime archaeology. Her pioneering spirit, blending art and science, continues to inspire and shape the field. This placement has been more than just an academic exercise; it has been a journey through Honor Frost’s life and legacy. It has challenged me to consider the multifaceted dimensions of the past and reminded me of the enduring impact dedicated individuals have in the ever-evolving narrative of maritime archaeology.

Thank you to Ma for all her work and her careful transcription of Honor Frost’s logbooks; this was an important addition to our archival finding aids for this popular and very special collection.

![Men's football team 1956-7 [MS1/7/291/22/4]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/picture5.jpg?w=451)

![Amistad Journal [MS404 A4171/6/1/1 Folder 1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/ms404_a4171_6_1_1_f1_amistad_journal.jpg?w=621)

![Photograph of Edwina Ashley showing examples of 1920s jewellery and makeup [MS62 MB3/63]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/ms62_mb3_63_1920s.jpg?w=751)

![Amistad and Cambria House Journals [MS404 A4171 6/1/1 and 6/2/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/basque-journals.jpg?w=300)

![Amistad Journal [MS404 A4171/6/1/1 Folder 1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/ms404_a4171_6_1_1_f1_amistad_journal.jpg)

![North Stoneham Camp [MS404/A4164/2/24]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/ms404_a4164_2_24_stonehamcamp.jpg)

![BCA’37: The Association for the UK Basque Children 70 Years Commemoration Event Programme [MS404/A4164/1/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/ms404_a4164_1_2_bca3770yearscommemorationprog.jpg?w=715)

![Souvenir programme for an 'All Spanish Concert by the Spanish Refugee Children from Wherstead Park, and West-End Spanish Artistes’ held at Ipswich in December 1937 [MS 370/8 A4110/1]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/ms370_8_a4110__1_quartetoofspanishchildren_ipswich-3.jpg?w=500)

![Pages from a Dorset carol book, 1803: part of the Rollo Woods music collection [MS 442/1/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/ms442_1_2_.jpg)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)