Friday 14 July 2023 marks 234 years since the storming of the Bastille in Paris in 1789. This was the iconic event of the French Revolution that came to symbolise the overthrow of the Ancien Régime; the name given to the political and social system that characterised France from the late Middle Ages until 1789. Bastille Day is now a public holiday in France.

The French Revolution is arguably the historical event most written-upon and most frequently subjected to the analysis of the historian. It is beyond the scope of this blog post to do justice to the historiography on the causes of the French Revolution, but suffice to say a range of political, economic, social and cultural factors have been offered as responsible for events unfolding as they did at the end of the eighteenth century.

The first episode in the Revolution was the summoning of the Estates General in May 1789, in order to address a financial crisis playing out between King Louis XVI and members of the French nobility. The Estates General was an assembly that represented the three estates of the realm: the clergy (First Estate), the nobility (Second Estate), and the commoners (Third Estate) but it had no true power in its own right, as unlike the English Parliament, it was not required to approve royal taxes or laws. The Estates General served as an advisory body to the monarch, primarily by presenting petitions from the various estates and consulting on fiscal policy. When it opened on 5 May 1789 it was the first time it had met since 1614.

In 1789 the First Estate comprised 100,000 Catholic clergy, owning 5–10% of the lands in France – all property of the First Estate was tax exempt. The Second Estate comprised the nobility, which consisted of 400,000 people, including women and children. By the time of the revolution, they had almost a monopoly over distinguished government service and under the principle of feudal precedent, they were not taxed. The Third Estate comprised about 25 million people (97% of the population), including the bourgeoisie (business owners and merchants), the peasantry, artisans and everyone else. Unlike the First and Second Estates, the Third Estate were compelled to pay taxes, yet the bourgeoisie often found ways to evade tax and become exempt. The greater burden of the French government, therefore, fell upon the poorest in French society: the peasantry and working poor; understandably there existed great resentment towards the upper classes.

The Estates General, instead of concerning itself with the financial crisis playing out in the country at large, began focussing instead on the question of how votes should be cast and how to divide power and representation amongst the three estates. On 17 June 1789 the Third Estate re-named themselves the National Assembly and on 20 June its members took the ‘Tennis Court Oath’ in the tennis court which had been built in 1686 for the use of the Versailles palace – their objective was to draw up a written constitution for France and to begin governing the country, with or without the involvement of the other two estates. A majority of members of the First Estate and many from the Second did in fact join with the new National Assembly. This moment marked the beginning of the French Revolution as it directly threatened the power of the absolute monarch – King Louis XVI. These developments were popular with many in Paris desperate for reform, relief and liberty.

On 11 July 1789 King Louis XVI (upon the advice of conservative nobles as well as his Queen Consort Marie Antoinette) dismissed his Finance Minister Jacques Necker, perceived as relatively favourable to the new National Assembly. This, combined with the fact that the King had brought troops to Paris (including foreign German and Swiss mercenary soldiers) put the people of Paris ill at ease, fearing as they did a conservative attack on the National Assembly. It was within this context that in July 1789 the people of Paris began demonstrating and storming properties to secure food as well as arms.

The Bastille was a medieval prison-fortress – a symbol of royal power in the heart of Paris. On the morning of the 14 July 1789 it was approached by a Parisian militia and ordered to surrender – a confused struggle then ensued throughout the day in which 98 attackers and one defender died, either in the fighting or subsequently from their wounds. If the Tennis Court Oath of 20 June marked the beginning of a liberal constitutional revolution promoted by the bourgeoisie, then it was the bloodshed and chaos at the Bastille that foreshadowed the violent phase of the revolution and the eventual downfall of the monarchy along with the rest of the Ancien Régime.

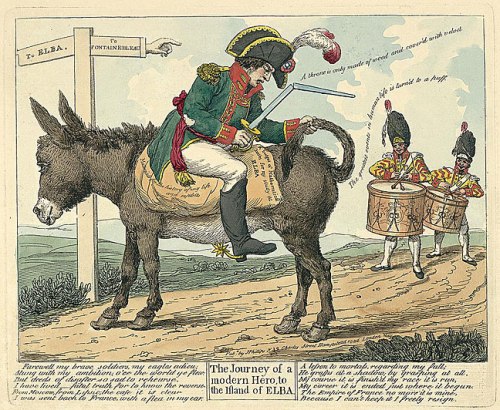

The National Assembly proceeded to abolish feudalism on 4 August 1789 and issued the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen on 26 August 1789, as it became increasingly radical. The events of the summer of 1789 were just the beginnings of the social and political revolution that unfolded in the following years, including the execution of King Louis XVI on 21 January 1793 and the rise of General Napoleon as Emperor of the French – his popularity with the French people driven by his victories in Europe and the Mediterranean.

The significance of the French Revolution was not confined to France or to the battlefields of Europe but was felt further afield; revolutions or social protest inspired by the events of 1789 broke out across Europe in the following years and decades. The great divides of nineteenth-century European politics were often framed in terms of liberal idealism on the one hand and conservative reaction on the other; even the ‘left-wing/right-wing’ terminology we use today has its origins in the seating arrangements for members of the National Assembly. This body was divided into supporters of the Ancien Regime to the president’s right and supporters of the revolution to his left. The Brabant Revolution of 1789-90 being a good example of how the French revolutionaries inspired others to rise up. This armed insurrection briefly overthrew the imperial rule of the Habsburgs and created a short-lived new state named the United Belgian States. In a letter from Henry Temple, second Viscount Palmerston, to Benjamin Mee dated 12 March 1790, the former gives his account of the causes of this dramatic episode in the Austrian Netherlands:

“[…] We were in some respect witnesses of the beginning of the Revolution in the Austrian Netherlands having been at Brussels when the insurgents entered the country. The facility with which they made themselves masters of it is to me incomprehensible. For as their number (I mean of men in arms) was very small, and the quarter from whence they must come, as well as all their motions perfectly known to the government, had the Imperial troops which could have been spared from garrisons been collected and properly stationed so as to have attacked them immediately, I conceive the business must have been ended as soon as it was begun. But as the whole country was on their side the opportunity once lost never was, nor I believe could have been, recovered.”

Letter from Henry Temple, second Viscount Palmerston to Benjamin Mee, 12 March 1790 [MS62/BR/11/15/5]

Palmerston goes on to describe how the poor treatment of the Roman Catholic church by the Emperor was responsible for the outbreak of violence, amidst confused attempts to reform an ancient constitution in need of amendment. He describes three distinct factions in the country: one in favour of an absolute sovereign; another in favour of an aristocratic council; and the third and most numerous in favour of a complete democracy: “In this they are supported by the example and influence of France and seem likely to pursue the same path of confusion and anarchy that their neighbours are treading.”

In the same letter, Palmerston goes on to describe the social unrest in France in disapproving terms, employing racist ideas in the process:

“Nothing I believe can exceed the wretched state of that country. In the capital they are undoing everything and loosening all the bonds of society while the horrors that are committed by mobs in various parts of the kingdom are such as would disgrace the most barbarous savages in the wilds of America. Whether anything like order and government is ever to come out of this chaos nobody I believe at present would venture to predict. Our politicians have been very foolishly debating and indeed quarrelling (that is to say Burke and Sheridan) about the proceedings in France, in our House of Commons, which seems to be the last place to discuss such a subject. Burke however was very fine upon it and is about to publish a pamphlet which I will send you when it comes out.”

The pamphlet Palmerston alludes to would be published by Edmund Burke in November 1790 as Reflections on the Revolution in France, now regarded as one of the most influential political pamphlets in modern history and considered a cornerstone of conservative political ideology.

A few years later in the late summer and early autumn of 1792, Lord Palmerston’s diary entries are quoted in the correspondence of Mary Mee, Viscountess Palmerston, sent to her brother Benjamin Mee during their travels through Europe:

“Paris at present is in the greatest state of insurrection possible. The Jacobins or the violent party carry everything before them and lay all the blame of the mischief that are resulting from their own absurdities on the King and Queen who are certainly in danger of their lives from the violence of the people and the little dependence they can have upon their guard who are only national troops. The assembly are distracted and seem in a mood of Frankish despair […]”

Letters from Mary Mee, Viscountess Palmerston, Boulogne to her brother, Benjamin Mee, 29 Jul – 6 Sep, 1792 [MS62/BR/11/18/6, p.5]

The political chaos and violence described by the Palmerstons led successively to the execution of King Louis XVI in January 1793; the assassination of the revolutionary and Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat by Charlotte Corday on 13 July 1793 (the day before Bastille Day); the ‘Reign of Terror’ of the Jacobins from September 1793 – July 1794; and the counter-revolutionary ‘White Terror’ from 1795. Tens of thousands of people died in these outbursts of violence.

The Jacobinism of Robespierre and others was strongly denounced by conservatives in Britain, as demonstrated in the political preface from an 1804 edition of The Anti-Jacobin:

“Ever since we commenced our labours, we have uniformly maintained, that the only effectual means of combating the system of usurpation and universal dominion which characterizes the French revolution in all its stages, was firm and extensive concert. The principles whence it sprung, the acts which it exhibited, and the characters which it formed, whatever might be their several diversities, all agreed in seeking the subjugation of mankind. This was a primary object of Brissot and his Girondins, Robespierre and his Terrorists, of Lepaux, and of Buonaparté.”

Rare Books per A, The Anti-Jacobin, Sep-Dec 1804

When Robespierre died on 28 July 1794 he was satirically eulogised in a piece titled ‘Sur la morte de Robespierre’ appearing in the volume Second tableau des prisons de Paris sous le règne de Robespierre, 1794-5; “everything fell under his blows – old age and childhood”:

“Sur la mort de Robespierre – Air – de versaillois – Quels accents, quels transports, en ce jour d’allegresse, Succedent tour-a-tour a la sombre tristesse! Vient de venger la liberte. Le cruel immoloit la timide inncence, Tout tomboit sous ses coups, la vieillesse et l’enfance. Francais! n’obeissez desormais, sosu vos loix, Qu’aux soutiens de la France, aux vengeurs de vos droits.”

[“On the death of Robespierre – Air – from Versailles – What accents, what transports, on this day of joy, Succeed in turn to dark sadness! Just avenged freedom. The cruel immolated timid innocence, everything fell under his blows, old age and childhood. French! henceforth obey, under your laws, only the supporters of France, the avengers of your rights.”]

Rare Books, Hartley Collection, DC140.5

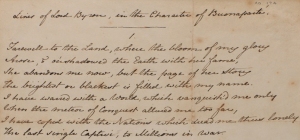

If we jump forward several years to the eve of the Battle of Waterloo, we find Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, first Duke of Wellington, writing to Louis Philippe, Duc d’Orleans, later King of the French Louis Philippe I, giving his own views on the cause of the French Revolution:

“In my opinion the King [King Louis XVI] was driven from his throne because he never had the real command over his army. This is a fact with which your Highness and I were well acquainted and which we have frequently lamented; and even if the trivial faults or rather follies of his civil administration had not been committed, I believe the same results would have been produced. We must consider the King then as the victim of a successful revolt of his army and of his army only; for whatever may be the opinions and feelings of some who took a prominent part in the revolution, and whatever the apathy of the great mass of the population of France, we may I think set it down as certain that even the first do not like the existing order of things, and that the last would if they dared it oppose it in arms.”

Copy of a letter from Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, first Duke of Wellington, to the Duc d’Orleans, 6 June 1815 [MS61/WP1/470/2/21]

Wellington’s emphasis on the importance of martial power and discipline might not be surprising, given that he was a Field Marshal on the verge of a major battle with Napoleon’s forces, but it echoes the idea expressed much later and by a very different general that ‘Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun’ – at least in the most immediate and pressing circumstances. Wellington’s notion that Louis XVI’s lack of military strength caused the French Revolution adds to a long list of economic, social and political factors held responsible.

It wasn’t until July 1880 that the French government officially adopted 14 July as the public holiday that we now recognise. The date was chosen partly to commemorate the storming of the Bastille in 1789 but also to commemorate the ‘Fête de la Fédération’, which was originally held on 14 July 1790 on the first anniversary of the capture of the Bastille. It was meant as a festival to celebrate the unity of the French people.

Bastille Day is now firmly established as the French national day. The 14 July 1945 marked the first celebration of Bastille Day subsequent to the total victory in Europe over Nazi Germany and it was the impetus for the signal sent from Lieutenant General F.A.M. Browning to the French Military Mission, sending good wishes on Bastille Day, 14 July 1945.

Whether you spend your Bastille Day at work, at leisure or brushing up on your French history – we in Special Collections wish you liberté, égalité et fraternité this 14 July!

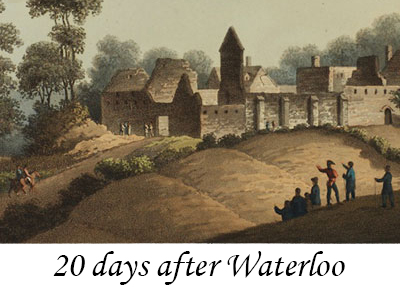

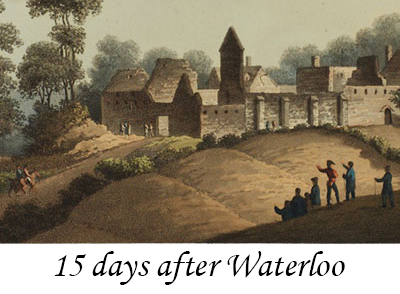

![Hougoumont, Waterloo [MS 351/6 A4170/7/4]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/ms351_6_a4170_7_4.jpg)

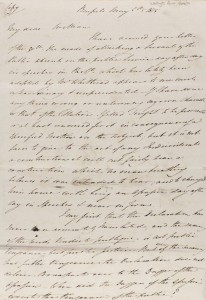

![Waterloo subscription, 1815 [MS 61 WP1/487/10]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/ms61_wp1_487_10.jpg)

![Lithograph of after the battle of Toulouse [MS 351/6 A4170/2]](https://specialcollectionsuniversityofsouthampton.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/ms351_6_a4170_2_n_0007crop.jpg?w=500)

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)