With events to mark the 80th Anniversary of D-Day taking place this week, we look at occasions in Southampton’s past when this commercial port has become a base for military expeditions or has been subject to threats of invasion itself.

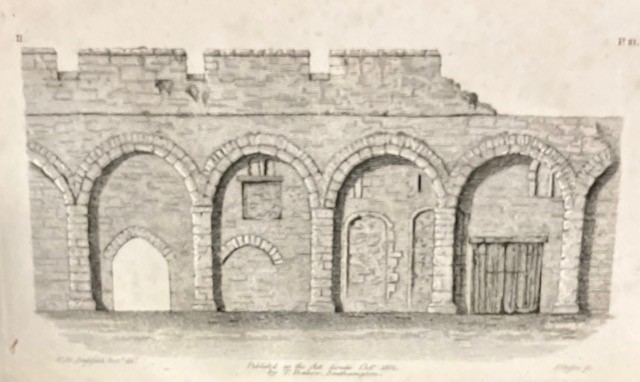

Beginning in the 14th century, the early years of the Hundred Years War saw not just a threat of invasion but a successful raid on Southampton by the French and their Genoese mercenaries. Arriving in October 1338 in a fleet of fifty galleys, they swiftly overran the town which had few defences to the south and west. The impact of the raid was severe. There was considerable loss of life on both sides and parts of the town were destroyed before the raiders left the next day. Stores of wool awaiting export and supplies of wine belonging to King Edward III, were plundered, adding to royal displeasure. Subsequently Southampton was ordered to strengthen its defences by completing the circuit of walls, the new western wall incorporating the waterfront walls of merchants’ houses, their windows and doors being blocked up. By the 1380s the town was enclosed by a wall which was fortified by twenty-nine towers.

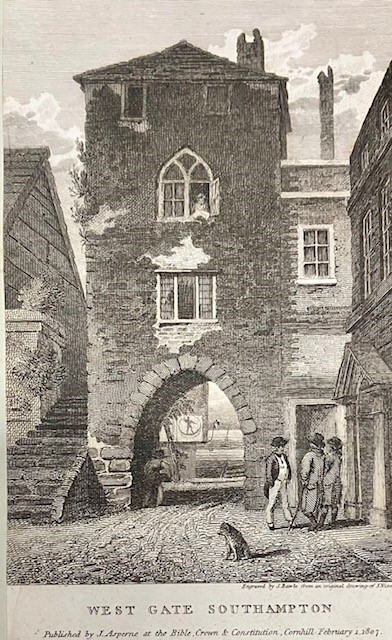

After the raid, Southampton became a garrison town, its complement of soldiers fluctuating in line with the frequent threats of invasion. Despite this, the local area was a mustering point for military expeditions to France. In 1345 Henry of Lancaster’s army set sail in over 100 ships and in July the following year the army which would fight at the Battle of Crecy assembled under the command of the King and the Black Prince. Similarly in 1356 troops were mustered for Normandy and the Battle of Poitier, and it was through the relatively new West Gate that many of the 11,000 men in Henry V’s army left for France and Agincourt in 1415.

The next three hundred years were by no means quiet in terms of wars fought and threats of invasion, but it was Britain’s entry into the French Revolutionary Wars in 1793 that brought huge numbers of soldiers to Southampton once again. Lord John Manners who visited in August 1795 writing:

We passed through a forest of transports which were partly waiting for troops, and were partly laden with horses for Lord Moira’s expedition. As soon as we got into the town, nothing but red coats and military were to be seen on all sides. … In short, we never saw a place that had such a military appearance as Southampton.

From: Robert Douch, Southampton 1540-1956: Visitors’ Descriptions of Southampton (Southampton, 1978) Cope SOU 91

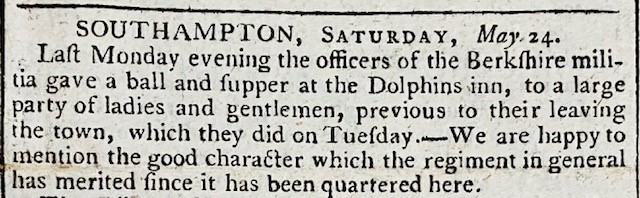

A ‘military appearance’ was not necessarily welcome in a town with a reputation as a spa resort although the resulting demand for goods and services contributed to the local economy. Whilst some visitors were probably deterred by preparations for war and fears of invasion, the many officers stationed in the town participated in its social life, attending balls, and staging their own entertainments.

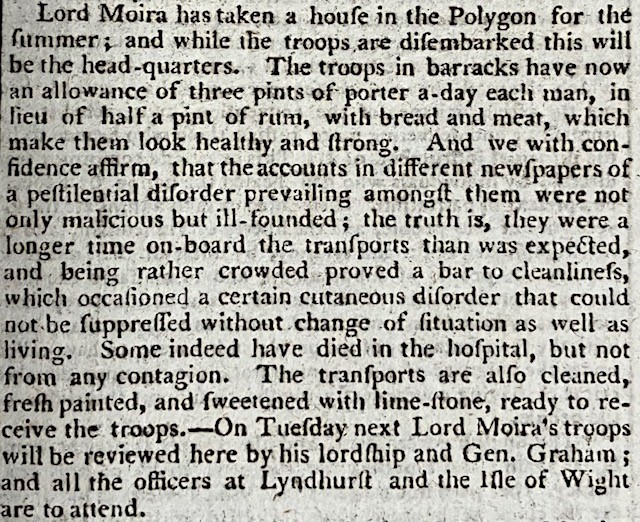

Inevitably tensions developed between the inhabitants and the troops. The billeting of soldiers in public houses was unpopular and the town successfully petitioned the government to provide barracks. Fears of disease arose in 1794 when eight regiments returned from an ill-fated expedition to Brittany with many of the men suffering from typhus. An empty sugar refinery was converted to a hospital, but the disease spread despite the Hampshire Chronicle‘s reassurances.

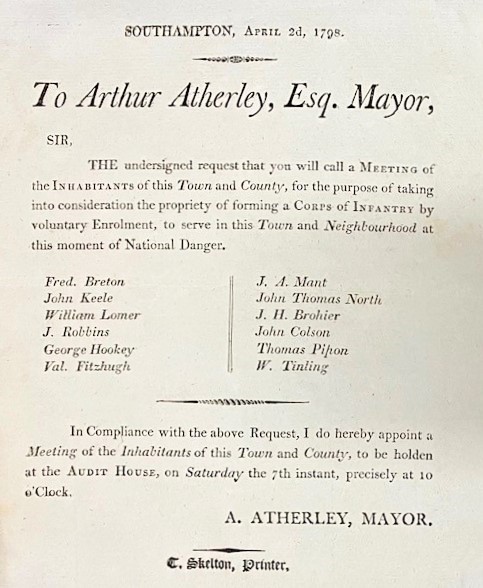

Fears of invasion later in the 1790s led to the formation of volunteer regiments to defend the local area, these being the Southampton Volunteer Cavalry and three infantry regiments, the Southampton Volunteers, Portswood Green Volunteers and the Associated Householders. Although the invasion never materialised, a false alarm during the Napoleonic Wars in May 1805, saw a new volunteer force acquit itself well, being armed and assembled within half an hour of the bugle sounding.

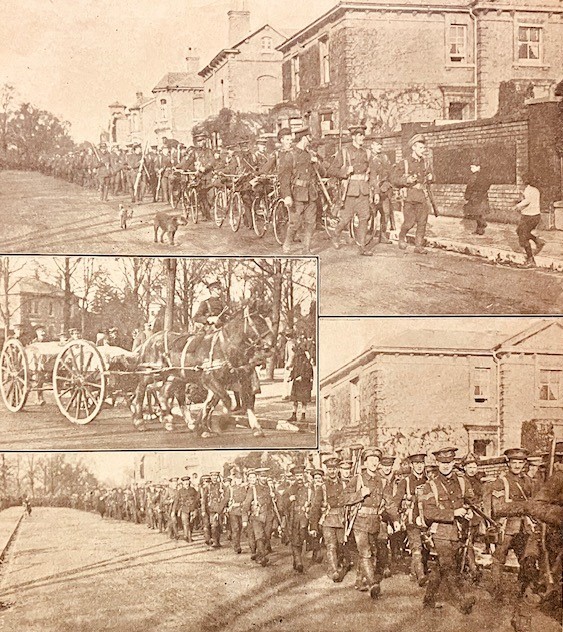

Throughout the nineteenth century, Southampton gained experience of ‘trooping’ both in peace and war, notably, in the Crimean War, 1853-1856 and the South African War, 1899-1902. The railway made a huge difference to the embarkation of troops and in August 1914, as Military Embarkation Port No.1, Southampton received 350 trains in 45 hours when the British Expeditionary Force left for France. Troop movements continued throughout the First World War and by its end, over 7 million men had passed through the port as well as 179,069 vehicles, 859,830 horses and 15,266 guns.

At the outset of the Second World War, Southampton had resumed its role as an embarkation port, sending men of the British Expeditionary Force to German-occupied France. But its proximity to the airfields of northern France meant its use was reduced until it took on its well-known role in Operation Overlord, or ‘D-Day’, the largest seaborne invasion in history. Again, troops and supplies were gathered in the surrounding area, designated as ‘Area C’ in 1942 when planning for the invasion began. In the summer of 1943, the U.S. Army Transportation Corps took over the docks which became the U.S. Army 14th Major Port, responsible for the embarkation of troops and equipment.

In Southampton preparations for the invasion saw the introduction of one-way systems on the roads and areas sealed off from the public. On D-Day itself around two thirds of the British invasion force left from the town, many troops boarding landing craft at Town Quay, whilst vessels preloaded with supplies waited in the Solent. After D-Day Southampton continued to send men to France, as well as receiving returning troops and prisoners of war with around 3.5 million members of the armed forces passing through the docks during this period.

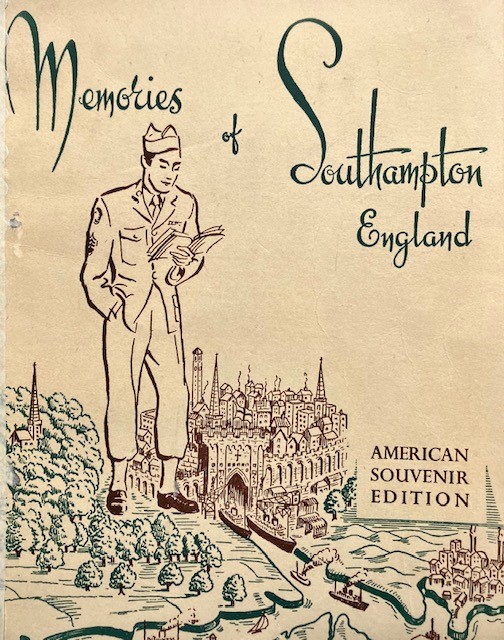

When the U.S. Army left Southampton in 1947 a plaque was added to the Mayflower Memorial in tribute to their troops, who were also awarded the Freedom of the Town. Another plaque at the Civic Centre recorded the gratitude of the U.S. Forces to Southampton and the links between the American troops and the town were highlighted in a booklet, Memories of Southampton, England, marketed in 1948 as a souvenir. To commemorate Southampton’s role, a D-Day Embroidery was stitched at the suggestion of Elsie Sandell, the well-known local historian. After these initial commemorations, subsequent major anniversaries of D-Day have seen the addition of plaques recording the role of Southampton’s dock workers and programmes of events to mark the occasion, as is the case on this 80th Anniversary.

After the Second Word War it seemed unlikely that Southampton would be used as a military embarkation port again, as troopships gave way to air transports, but just over forty years after D-Day, Southampton once again saw troops embarking for war as the Canberra, the Norland and later the QE2 left for the Falklands.

For a look at D-Day seen through the papers and photographs of the U.S. Colonel James O’Donald Mays, held in the University Archives, see our blog marking the 75th Anniversary.

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)