The idea of food and memory – stimulated by the senses – has become more commonly recognised and Jon Holtzman in his review of food and memory in 2006, highlighted the power of food in maintaining connections, facilitating reflective memory of past events and experiences. The food that we encounter throughout our lives, it can be argued, leaves memories that frame our past.

Certainly within the oral history interview accounts of the Basque child refugees who arrived in the UK in May 1937 that we hold in the Special Collections there are various mentions of food which act as reference points for the children in their life journey and for the memories created.

As Vicente Cañada noted the sound of English as well as smells and tastes unlocked memories on his return to the UK: “I heard things again that I had forgotten but which had stayed in my subconscious and the same with smells and tastes that I had forgotten but remembered of food and soaps and stuff.”

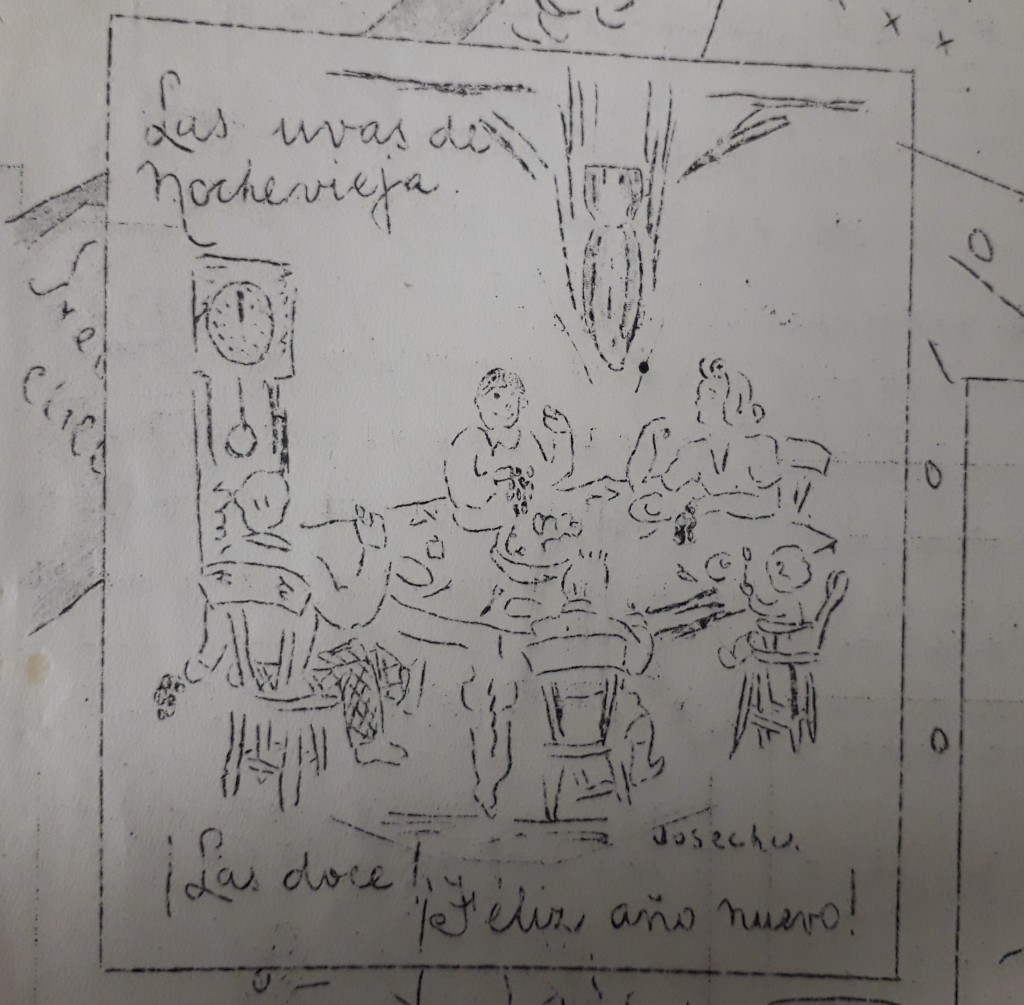

In the food narratives relating to the life in the Basque country the children recreate a sense of their family through memories of favourite dishes eaten at home as well as where they would have eaten together as a family.

Jose Armolea recalls a favourite dish cooked by his mother:

“I’m talking about Aluvia. Aluvia’s a very well-known Spanish dish which is red beans which actually, it’s cooked with chorizo and a good portion of pork, fatty pork to give if flavour and indeed you can go to some places in Spain today where they specialise and it is a dish that you go out specially to eat because it is, if it’s done properly, superb, so that’s what, that’s one good dish. Garabanzos, chicken peas, that’s another one.”

And he also spoke of how the family sat down together for dinner each day and “we would always sit for breakfast together as well and in the middle of the kitchen you got a long table with stools that you can push underneath there when everybody had finished eating but that’s where we would eat normally. We wouldn’t have any ritual of eating in the dining room by the balcony”.

Maria Louise Toole’s mother was a professional cook and she had fond memories of the meals that she produced, including various Basque dishes: “a lot of fish, everybody says that in cookery books. They’re excellent at the fish dishes, and meat and things like that … and stews, and txakoli the fishermen do that in the boats … and they have their own puddings and things like that.”

Others share deep memories of the impact on food caused by the Spanish Civil War.

As Felix Amat recalls “during the blockade of Bilbao, things were even worse. The only things we very often all had was el garbanzos: chickpeas”: and chickpeas remain something that he has disliked ever since.

Or the fact that as supplies became more scarce, as Francisco Robles Hernando remembers, “we used to have the same food and eat lots of good fruit and all that, but … for one year we hardly had any of that. In Spain we were eating horse meat and my mother used to queue up for four hours for a piece of horse meat”.

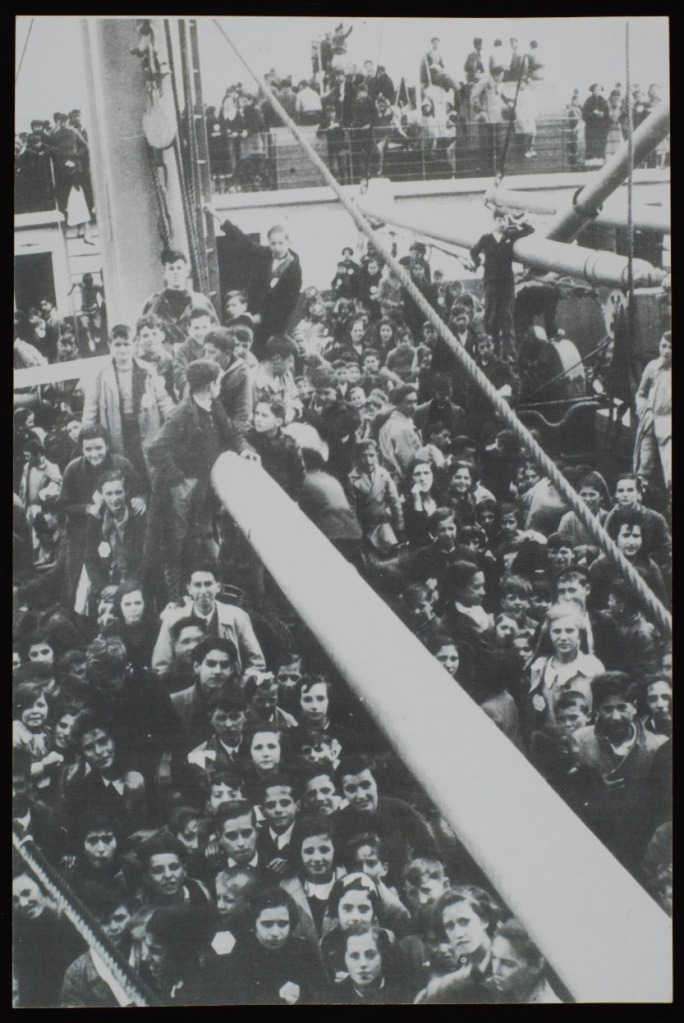

The trauma of the journey on the Habana, where most of the children were ill, includes tales of both the delight of the amount of food and the fact that it might have contributed to their illness.

As Valeriana Flores notes “We were so ill, all of us. I think probably to a certain extent it was the way we were fed. The food that was available was very strong, too strong probably to what we had been used to eating and I remember being sick the whole journey through.”

Felix Amat remembers that “when we eventually got on the Habana, the ship to come to England, they gave us some fresh rolls, white rolls. They were great. But unfortunately, as most of them will tell you, we were all sick”.

And Josefina Savery also recalls the plentiful supply of food on the boat. “They had white bread and chorizo, and that was like manna from heaven. It was absolutely marvellous. And because we went in the boat in alphabetical order, and we were “A”, I got a bunk for my brother and one for myself. And Gerry said “Oh I’m hungry, and look, they’ve got chorizo”, so I went to get it for him – when I came back, my bunk had gone. So I spent all the journey to Southampton on deck, being terribly sick. I’m a poor sailor. So it wasn’t a very exciting journey.”

Memories of the food the children encountered when they arrived in the UK, first at the camp in Eastleigh and then at the places they stayed in elsewhere, show something of the adjustments that they had to make to the differences between life in Spain and that in Britain.

Of the situation at the camp in Eastleigh, Josefina Stubbs recalls: “If you didn’t eat your food you didn’t get your pudding which was either a banana, an apple or an orange… We’d have a bowl and queue up… They’d put so much on your plate and then you’d sit down at a wooden table… my sister would go first and then start eating as quickly as she could. I would follow, then sit next to her and when she’d eaten her portion she would swap plates with me and she’d have mine. Then she could get her pudding and I could get mine and that’s what I used to live on… There were mainly dishes like mince-meat and brown gravy. To me it was horrible. I didn’t mind the mashed potatoes so much but the food was not very Spanish.”

And Rafael Leandro Flores remembers that “we ate very basic things of course like barley and onion soups and things like that. Corned beef. They put up a stall and I think Horlicks was a new thing in England and we would queue up to take a glass… and go back to the end of the queue again and take another”.

For Carmen Wood the memories of the food she ate are more vague, but she was clear that “whatever it was, I didn’t like it. We had fish, which was so different to what we were used to. Didn’t taste very nice. The bread was alright, in fact it was very pleasant and very welcome. I can’t remember what we drank. Stuck to water, I suppose”.

Francisco Robles Hernando remembered the “white bread for a start, plenty of butter, marmalade, jam, you know all the things that we missed in Spain during the War. We had tins of peaches. They gave us everything. Apples and all that … they used to bring apples from Kent, very good apples. We lacked for nothing in the colonies. I was lucky, others wasn’t so lucky as me but the ones that we were in, we were very well taken care of…

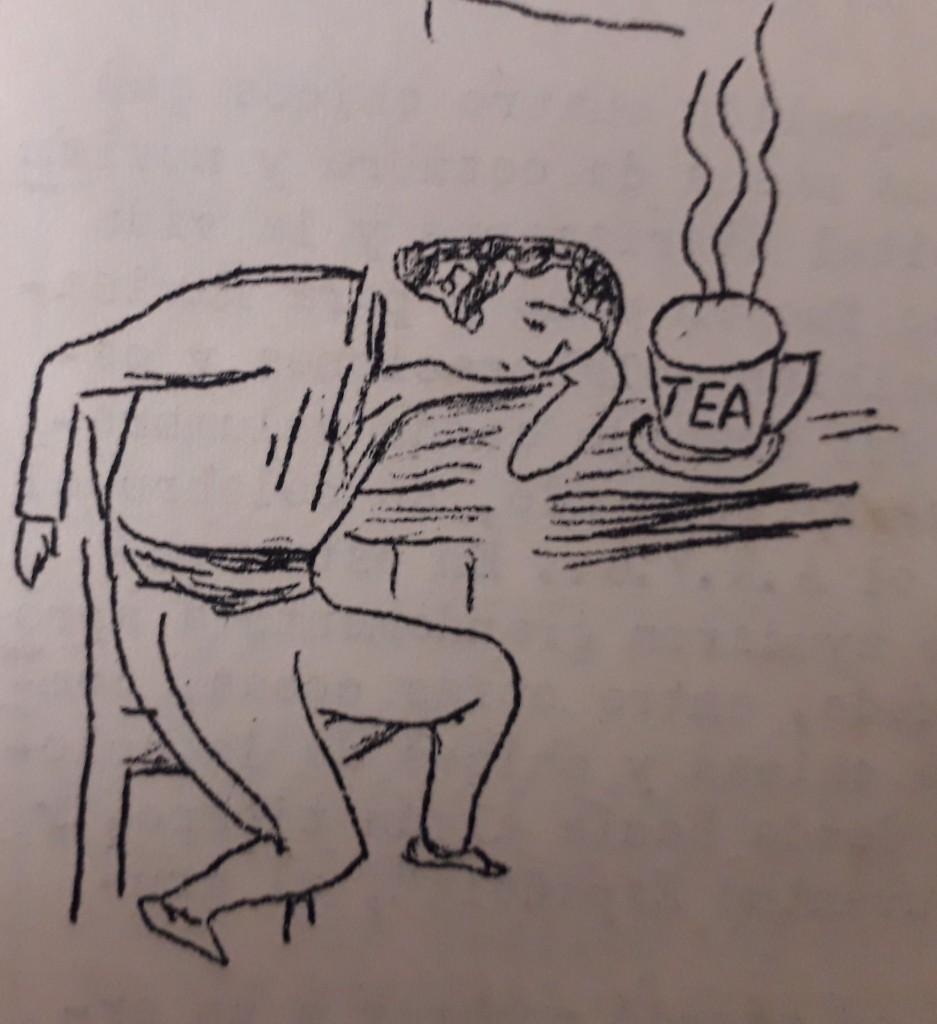

We had custard, custard pies and all that kind of thing there, cornflakes in the mornings that I never had before, never, you know in the morning in Spain you … cup of coffee with lots of bread there. Good. But all this kind of stuff like cornflakes and all that we never had it and we loved it. But we were invited to … I was invited to a home in Ipswich, two of us were invited to this home and they gave us a cup of tea with scones and I was sick because I never had tea before …”

Valeriana Flores’s recall of the bread was that it was awful, but “I don’t think in Spain I had seen a banana. I don’t think I saw a banana until I got to England. That was the first time I came across a banana because the food we ate in Spain was always grown in Spain, especially at that time”.

While the reception by the British government for the children could be said to be less than warm, this was countered by the kindness of the ordinary people. Agustina Pérez felt overwhelmed by the sympathy and attention displayed by the British people: “When we were put on a train, it stopped quite a bit and every time it stopped at a state people there came out and were giving us chocolates and sweets. It was lovely.”

Manuel Rodriguez recalls that “when I started work in the Co-op Mrs Simpson she took me to her mother’s house. She gave me the best dinners I ever had. Beautiful! Today I’d give anything, I’d walk to Milford for one of them.”

And Rafael Flores paid tribute to a generous hostess: “Peggy Gibson was a tremendous woman…. She had a very big house near Birmingham and she would lay out a table full of everything; she took us there for tea and it was something that we’d never known. Cakes, tea and bread and butter and jams and cake and a lot of cutlery.”

Nostalgia for the recipes of home might well be the reason for the creation of a typescript recipe book in the collection of Caridad (Carito) and Marina Rodriguez Vega. Arranged into sections it includes recipes for broths and soups, macaroni and pasta, paella, vegetables, hors d’oeuvres, garnishes, eggs, sauces, fish, fried, cold cuts, meats in sauce, pork and lamb, desserts, cakes. Whether this was created as an act of remembrance or of nostalgia, it is a work that shows the effort and importance placed on remembering the dishes of the children’s past. Do join us for a future blog when we shall be trying out some of the recipes.

![Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's football team, 1953-4 [photo_MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268168_f26eed63ef_s.jpg)

![Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's rowing team, 1961-2 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079577_3b7acbde42_s.jpg)

![Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Men's rugby team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50089268523_4f2c587220_s.jpg)

![Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4] Women's hockey team, 1953-4 [MS1_7_291_22_4]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50090079692_28114e9c7d_s.jpg)